Woke Colleges Are Assembly Lines for Conformity

The stakes are much higher than most people realize

By Charles Lipson

Don’t be fooled by universities’ incessant chatter about “diversity.” Most are poster children for ideological conformity and proud of it. The faculty, students, and administrators know it. Indeed, many welcome it since their views are so obviously right and other views so obviously wrong. They believe discordant views are so objectionable that no one should express them publicly.

What views are now considered beyond the pale? They almost always involve ordinary political differences. We are not talking here about direct physical threats. Those are already illegal, and universities rightly deal with them. They don’t have to face neo-Nazi marches. Nor is anyone advocating such noxious ideas as genocide, slavery, or child molestation. Speech about those subjects might be legal, but virtually nobody is making the case for them. That is not what the fight for freedom of speech on campus is about. It is about the freedom to voice—or even hear—unpopular views on topics such as merit-based admissions, affirmative action, transgender competition in women’s sports, abortion, and support for Israel.

These are perfectly legitimate topics, and students ought to be free to hear different ideas about them. They are hotly contested topics in America’s body politic. That’s how democracies work. Not so on college campuses, where the “wrong views” are not just minority opinions. They are verboten, and so are the people who dare express them. Challenging this repressive conformity invites condemnation, severs friendships, and threatens careers. It is hardly surprising that few rise to challenge it.

Worse yet, university leaders seldom do. They have a fundamental responsibility to defend open discourse, and they have largely abdicated it. Shame on them. Instead of defending the free expression of unpopular views, they condemn them and flaunt their own virtue. That’s what Princeton’s president Christopher Eisgruber did when he attacked classics professor Joshua Katz, saying Katz had not exercised free speech “responsibly” when he allegedly gave a “false description” of a Black student group. Katz’s own department condemned him, too, though the university finally decided the professor would not be formally punished. They will save the ducking chair for another day.

Eisgruber is hardly alone. University leaders have failed, en masse, to confront the pervasive challenges to free speech on campus. It is their responsibility because enforced ideological conformity is antithetical to universities’ basic mission. It damages teaching, learning, and research. It inflicts that damage even if you and I wholeheartedly agree with the predominant views. Letting them go uncontested invites intellectual flabbiness. Allowing them to be coerced into silence invites mob rule and ideological uniformity in what should be a bastion of open and vigorous debate.

It is also wrong for official units of the university, like Princeton’s classics department, to express their institutional views on political issues. Although faculty and staff members are welcome to express their own views individually, taking an institutional position inevitably chills the speech of any faculty or students who might disagree. Top officials at the university should be even more scrupulous. Again, the goal is to encourage open discourse on campus, not chill or suppress it.

High Stakes

Higher education demands this free discourse, including vigorous disagreement, using well-established standards for logical rigor and empirical evidence. Without those standards and spirited debate, instruction degenerates into indoctrination. That is precisely what has happened at too many universities and too many departments, especially those in the humanities and social sciences. Even faculty and students working in the hard sciences—once presumed to be above the political fray—are increasingly succumbing to demands for ideological conformity. The problem also has spread to K–12 education—mainly in history, social studies, and English—where it is inundating students who are even less prepared to resist it than their older siblings.

There are few countervailing currents against these pressures for conformity, and education is worse off for it. And the stakes are higher than most people realize.

Whether the prevailing views are right or wrong, they degrade the opportunity for teaching and learning, innovative research, and students’ personal development. It’s easy to find examples. Consider, for instance, the current generally accepted idea that the earth was formed about 4.5 billion years ago. No one believed that in the early 1800s. They read the family trees in Genesis and agreed it was roughly 4,000 years old, at most. That view changed only because it was challenged by Charles Lyell and other geologists, who overcame fierce religious opposition.

This new understanding of geology meant that skeletal artefacts found in rock formations were themselves ancient and could be dated to different rock layers, formed in different eras. Charles Darwin carried Lyell’s textbook on the voyage of the H.M.S. Beagle, and it proved crucial as he formulated evolutionary theory. Modern versions of Darwin’s theory depend on still other scientific discoveries, particularly those in genetics. All are debated freely, tested empirically, and challenged theoretically.

Challenging settled views like this is not just how science works. It is how all systematic research and development works. Thomas Edison, who founded the modern research lab, made that point when he was asked about his failed experiments. “I have not failed. I've just found 10,000 ways that won't work.” That is usually taken to mean he was persistent. He certainly was. But Edison’s comment has a second, equally important meaning: that he had a right to try those experiments, to get it wrong as well as right, and to keep trying. Efforts like his, along with the right to capture the profits they might generate, are the technological foundation of our modern world’s unprecedented richness.

This fruitful contestation of different views, different approaches, and different conjectures goes well beyond science. It is the foundation of Anglo-American jurisprudence, where each side presents its own best case, its own best evidence, and its own interpretations, and then challenges the other side’s. It’s all a nonviolent contest of thrust and counterthrust. Democracy itself depends on such contestation, on politicians’ and publicists’ ability to make their cases and on citizens’ ability to hear and assess them. It’s why democracies tend to be more prosperous and, in virtually every way, more successful than autocracies and other systems that prohibit or stifle open debate.

But this open forum is under sustained attack, even in the world’s old democracies. The same pernicious practices that harm education have spread to mainstream news organizations and the tech giants that control online discussion. They are suppressing and thus distorting discussion of important public issues. Search (on Google) and ye shall not find, not if the search engine wants to hide results from sites it doesn’t like.

Major corporations and sports leagues have followed on bended knee for the same reasons they buckled to McCarthyism in the 1950s. These organizations aren’t any more moral now than they were then. They aren’t any less driven to maximize profits. Their abiding belief, then and now, is “duck and cover your behind.” They are simply doing it differently these days because the political environment is different.

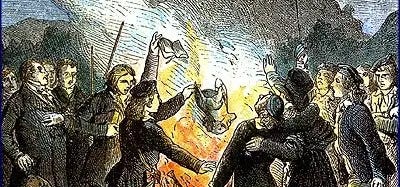

Conformity itself is hardly new. It is an age-old social practice, reinforced wherever there are tight social bonds. What’s new, historically, is free debate. That is a unique Western achievement, the product largely of Reformation Christianity’s idea that each believer should read and interpret the Bible for himself and the Enlightenment ideal that all social practices are subject to rational criticism. The noblest expressions of these ideas are the First Amendment to the US Constitution, its philosophical defense by John Stuart Mill, and its embodiment in the modern research university. These achievements are not just bedrocks of free expression, they are bedrocks of liberal democracy itself. They are precious achievements, hard won and fragile. One mark of that fragility is that it is unpopular now even to speak of these Western achievements.

In today’s universities, far too many are determined to smash those achievements, to close the gates of discussion to block untoward opinions from entering. That’s always the goal of zealots. What’s new and deeply troubling is their dominance inside the ivied walls.

Universities, K–12 education, and now news organizations, social media platforms, large corporations, and sports leagues have not only propagated this stultifying ideological conformity, but they have provided its specific content. It is cloaked in benign but misleading terms such as “social justice” and “diversity.” The “justice” of it all is debatable, and it is the very opposite of “diverse.”

“Diversity” as Political Code

On campus and off, “diversity” has become an Orwellian code word for the racial color-coding of students and faculty. To see that clearly, ask yourself how Harvard, Duke, or Stanford would describe three newly admitted students, one White, one Black, one Hispanic, all of them raised in the same wealthy suburb, all children of prominent attorneys, all wearing buttons saying “I Support Single-Payer Healthcare.” The answer is easy: each university would congratulate itself for recruiting such a diverse class. The New York Times and Washington Post would praise the universities and hope that these students would later contribute to their newsrooms’ diversity. This univocal elite would trumpet its own moral superiority while flagellating our country’s past. They march, arm-in-arm, from Scarsdale to Cambridge to Brooklyn Heights.

This self-congratulation corrupts both language and thinking. If diversity means anything, it must cover more than one dimension. It must mean different backgrounds, religions, ethnicities, academic interests, viewpoints, and so on. Racial difference is part of it—a particularly important part, given America’s history—but still only part. It is also diverse to include some well-qualified students who come from Appalachia, some whose parents work at Walmart, and some who won the blue ribbon for best pig at the Iowa State Fair. (Conversely, it does those students no favor to recruit them to competitive schools if they are ill prepared and are expected to perform near the bottom of the class. We know, from hard experience, that they are much more likely to drop out or choose easy majors rather than pursue their dreams.)

Diversity goes beyond the students who are admitted. It should include some campus speakers who support greater school choice, more funding for police, less immigration, and other minority (at least on campus) opinions, not because those views are necessarily right but because students need to hear and consider them. That’s the only way for those who have come to learn and grow intellectually to make up their minds intelligently. If the students’ dominant view were that police funding should be doubled, it would be just as important for them to hear voices urging funding cuts and explaining why they matter. Students who disrupt these controversial talks and prevent others from hearing them should face serious consequences, not mild slaps on the wrist like those received at Middlebury after students rioted to prevent scholar and author Charles Murray from speaking. Free speech means demonstrating outside the talks, not inside the auditorium; it means peaceful protests, not violent ones.

What Can Students Do?

Students entering this den of college conformity can prepare for it in four ways—and improve their education in the process. Actually, these four suggestions are good advice for anyone, at any age, facing intense institutional pressure to conform.

Listen to alternative views and criticism of ideas you currently hold. That does not necessarily mean changing your views. It means testing and reevaluating them.

Try not to be swept away by peer pressure. One way to minimize it is to widen your social circle.

Learn to make coherent arguments. Name-calling is not an argument, damn it.

Report teachers or other authority figures who demand ideological conformity to get a good grade or promotion. Your academic adviser or human resources department can tell you confidentially how to lodge a complaint and what evidence you need to support it.

Remember: just because others are marching in lockstep doesn’t mean you have to join their parade. Make up your own mind, and do it without fear or favor. No lesson in college is more important.