Without World’s Fairs, Can America Imagine Its Future?

World’s Fairs are but a remnant of a time when America thought big

I have a small pewter oval box, about 2 inches long, engraved with a magic spell: “World’s Fair 1893.” It sat on my grandma’s dresser for seven decades. She also had a ticket in her collection of papers: World’s Columbian Exposition, Manhattan Day, Oct. 21st. From this I deduce that my great-grandfather and his wife and young daughter took the buggy from Harwood, North Dakota, to Fargo, whereupon they took the train to Chicago—and entered a world whose beauty, order, majesty and wonder may have stayed with them all their lives.

I can imagine my great-grandfather, a Grand Army of the Republic veteran, telling the old fellows down at the GAR hall what he had seen. The splash of light at night, illuminating the stately classical structures, their alabaster reflections shimmering in the dark lagoon. The gold Statue of the Republic, glowing with hope and promise. The halls full of inventions. The great Ferris wheel ploughing a furrow in the sky. He might have leaned closer and said he’d slipped away from his wife and paid a visit to see Little Egypt dance. And gentlemen, the stories are true.

He saved the ticket. He must have bought his wife, or young daughter, the hat-pin box. He may have seen it on the dressing table years later and thought of the trip, of the tumult of Chicago, the tall towers, the great lake beyond, the stink of the stockyards, the gleaming White City rising like a dream of Rome. He might have thought about how it ended in fire, how he felt a small pang upon reading of its destruction. It was never meant to last. But here was this small silver box to prove it had not been a mirage, and that he had walked its streets and thought: This is the world to come.

——

Many years ago in New York, in a parking-ramp flea market, I found an extraordinary remnant of the 1939 World’s Fair. It was a mashup of the iconic—sorry, but the cliche applies—Trylon and Perisphere. Some sort of bottle with a screw-top. Absolutely hideous.

Of course, I had to buy it. The vendor had a few more items: a ticket, a button, a guide to an exhibit, a book of views. I bought the lot. They sit on a shelf with my World’s Fairs collection, including a glass paperweight from the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair. It has a picture of the Travel and Transport Building, which looks like a moon base built by Mayans. It’s next to my great-grandfather’s ticket. I wonder what the man who was left for dead on the battlefield in 1864 would have thought of the modernistic visions of the Fair that followed the one he visited.

He might have thought that the old world had fallen, utterly, and that a new civilization had arisen in its ashes. He wouldn’t have been entirely wrong.

——

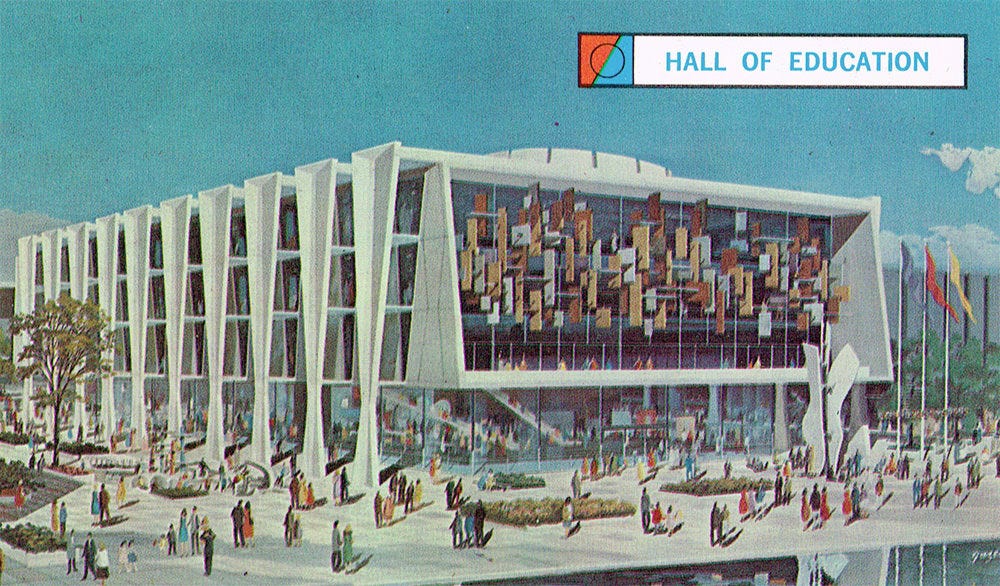

The other day a friend sent a pamphlet about the 1964 World’s Fair. It was produced by a whiskey company, and contained drink recipes to enjoy whether you were at the Fair, or at home contemplating the new world the Fair represented. The Unisphere figured prominently in the illustrations. Everyone in America knew what it was: an enormous globe made of steel. The old world was dense and thick, trudging around the sun. The new world was light and confident, stripped to the basics, the old impediments shed.

I wondered why I’d never come across many 1964 World’s Fair items in my antique store excavations. The generation that brought things home from the Fair is passing in waves, their possessions sent to the thrift stores by children indifferent to their meaning, or just burdened by the obligation of carrying the items forward. Maybe there wasn’t good merch. The only thing I’ve found and bought was a deck of cards that showed the various buildings at the Fair. Baroque modernism at its inflection point, yearning to be kitschy and inventive, but still worried about getting a tut-tut finger-wag of disapproval from the ghosts of the Bauhaus.

The 1964 World’s Fair was square culture: the last parade for the grown-ups. Look at the videos that survive, and you see the dads with their skinny ties, short-sleeve dress shirts and high-and-tight haircuts, Instamatic cameras and Winstons. Moms with hairstyles that could’ve come out of a soft-serve ice cream machine. Young girls with Clairol-washed flip ’dos. The children look like junior adults. They probably grew up to forget the Fair, renounce it, then paused when they found photos in a box after the parents died and wondered where that world went.

——

It’s been decades since a World’s Fair last made a mark on the American imagination. Knoxville held one in 1982, and while a few may remember its landmark symbol—the Sunsphere—most Americans would look at a picture of the thing and think it was a failed Vegas attraction. The ’82 World’s Fair was a “specialized Expo,” dedicated to a particular theme—in this case, energy. Same thing with our last Fair, the ill-fated New Orleans entry of 1984, which had the distinction of being the first Fair to go bankrupt while it was happening, instead of afterwards.

True World’s Fairs are World Expositions: Come one, come all. They’re still happening. The next one’s in 2025 in Osaka. Dubai had one in 2020. Riyadh will host one in 2030, and the theme is “The Era of Change: Together for a Foresighted Tomorrow,” which sounds like Chat-GPT and Davos got married. The Fairs still have their landmark icons—Milan in 2015 had a glowing “Tree of Life.” Dubai had… a big blue dome. Shanghai had a big, illuminated funnel.

Anyone remember the buzz? No one in the States pays much attention to these because they’re elsewhere. The last foreign World’s Fair that seemed to have any profile in the USA was the Brussels Expo of 1958, perhaps because it was the first since World War II. And it had a big abstract atom as its symbol, mirroring the Fair’s slogan: “For God’s Sake Can We Just Not Use This to Blow Everything the Hell Up Again.”

Kidding. The slogan was “Evaluation of the world for a more humane world.” Sounds a little better in French.

Now and then, you hear about the U.S. making a pitch. Bloomington, Minnesota, home of the nation’s biggest shopping mall, tried to get a specialized Expo for 2027, but lost to Belgrade, Serbia. We’ll probably try again, but you get the feeling that the international body that hands out locations figures we’ve had our time in the sun. The world is so much more than the United States, after all. Everyone has our number. What surprises could we offer?

And it’s not as if we’re clamoring for another one. The United States Information Agency was the government body that handled our participation in World’s Fairs, and Congress axed that agency in 1998. Who knows—maybe they sent us a letter asking if we’d like to host one, and it came back “no such address.”

Americans seem OK with this. After all, we have our permanent theme parks, which have all of the fantastical environments without the spinach. There’s no Palace of Industrial Machinery at Disneyworld, no Pavilion of Cellophane at Six Flags.

And that’s a pity. The exhibits designed to show American know-how and can-do are one of the things that made the old World’s Fairs great. Mr. Otis showed off his safety-brake elevator at the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations in New York City in 1853, a proto-Fair. The hot dog was supposedly introduced at the 1893 Columbian Expo. The 1939 Fair had Elektro, a robot who talked and smoked cigarettes—and ended up in a 1960s B-movie, “Sex Kittens Go to College.”

Oh, and it had this thing called “television.” RCA inaugurated its first regular schedule at the Fair, and people who’d only read about TV in magazines saw it work. It was here. It was real. The 1964 World’s Fair had the Picturephone, a video-calling system that everyone knew would be the logical evolution of the telephone.

In short: The World’s Fair gave us a glimpse of things to come. Wonderful things! “I have seen the future,” said the button you got when you visited General Motors’ Futurama pavilion at the ’39 Fair, and you could go back to Nebraska or Florida or Oregon knowing you had been offered a glimpse of the world en route.

Of course, the new world never arrives all at once, fully formed and expertly landscaped. We get bits and pieces, dribs and drabs. For example, the classical architecture of the 1893 Fair—and a reprise of the style at 1904’s St. Louis Expo—gave rise to the “City Beautiful” movement. People who’d gone to see the White City in Chicago went home, looked at their tired old buildings and messy rambling streets, and thought: Why not drive a diagonal boulevard through this town and line the streets with Beaux-Arts buildings? Many cities commissioned plans; few followed through. But now and then you might find a remnant of something that followed the City Beautiful ideas, like the ruins of the Forum in Rome.

Not all of the visions aged well. The Futurama of the 1939 Fair laid out a version of the future that was ambitious and intellectual, a “Things To Come” technocratic assurance that top men, smart men, men with plans, would shape the cities into great efficient machines, not style-garbled patchworks of offices and shops. Broad streets would cut between severe and aloof towers. Empty plazas with modern sculpture. Elevated sidewalks. A bit too much Le Corbusier and not enough Hugh Ferriss.

But the optimism was there. The optimism is always there. The American iterations of the World’s Fair had such brash faith in the ingenuity and strength of the nation. If you only have a thumbnail knowledge of the Depression—everything in sepia, breadlines, the skies darkened by brokers jumping from windows, dust bowls—then the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago seems like a mad idea. Throwing a party in the middle of a plague. The architecture seemed to say: “We know, we know—the old world’s dead. Let’s start the whole thing over with stark towers that look like Eloi churches from the year 6039. Also, here’s a charming old-world German village!” It’s daft, but it had that can-do spirit, the clean-slate American impulse.

The strange new forms of the Streamline Moderne style worked their way into the nation’s cities, thanks to banks and Works Progress Administration projects and post offices, so the abstract style of the 1939 Fair wasn’t as jarring as the 1933 Chicago example. This was the way everything was headed. The Wonder Bread building will look like a Buck Rogers brothel, and that’s fine.

Alas, war. By the time we started building again, Moderne was anything but. Out with the serenely intellectual curves of the Streamline style, in with the boxy lines of the IBM mainframe. The World’s Fairs of 1962 and 1964 pushed back against the straitjacket of Modernism and displayed some wildly imaginative architecture. The Coca-Cola Pavilion in 1964 was like a Gothic church built for storks:

This thing looks like some alien machine that walks around the planet and eats people:

Not much of the ’60s World’s Fair architecture was influential. If it showed up anywhere else, it was the graveyard of bad architectural movements, the ’60s and ’70s college campus. But it was fun. You can’t say the 1962 Fair wasn’t as optimistic and future-yearning as its predecessors, because nothing sums up America like the shot at the end of “It Happened at the World’s Fair”:

Elvis shakes hands with a NASA recruiter. New Frontier, baby. We’re goin’ to the moon, and we’re gonna have a rocking’ good time.

——

Everyone who has a mild interest in the World’s Fair has a favorite they’d like to visit in a time machine. I’m torn. Maybe the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco in 1939, the one that gets overshadowed. Maybe ’62 or ’64, so I could see the world of my parents. Maybe 1893, where I could find myself next to a slight old man named Charles who had come from North Dakota. The temptation to tell him that his land was still in the family would be too great, though; can’t mess with the space-time continuum.

So 1939 it is. I’ve a good reason. One of the items I bought in the New York flea market was a small envelope that contained a “golden key.” They were given to people who stayed at a particular group of hotels. A car was given away every day, and one key would win it. My envelope is unopened. Whoever got it at the hotel never made it over to the underwhelming booth where you tried your luck. Maybe this key’s the one.

Thinking about World’s Fairs has always been a means of traveling through the land of the past. I look at the envelope and contemplate its mystery. The key slides in, hand in glove, and I hear the engine of America catch the spark and roar to life.