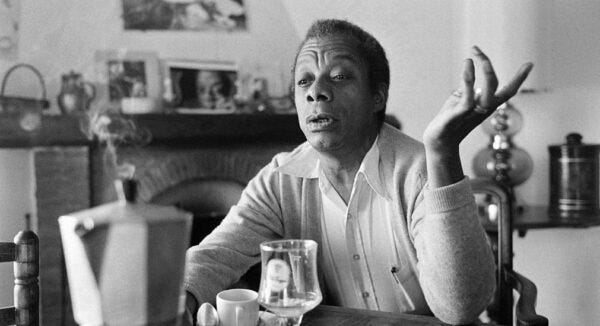

What James Baldwin Can Teach Us About Race and Identity in America Today

The mid-20th century writer suggested that both white and Black Americans need to grapple with the deeper issues of who they truly are

By Sahil Handa

The first time I read James Baldwin, I didn’t know he was Black. I was a skinny 17-year-old Indian boy with braces, and I picked up a slim novel called “Giovanni’s Room” and finished it in a week. I loved it—its intensity, its honesty, its moral complexity. I loved it so much that I gave it to my mother and asked her to read it. She did and thought it was my way of coming out as gay.

It never crossed my mind that Baldwin might be Black because the novel does not contain a single Black character. The novel’s protagonist, David, is white, and Baldwin once told an interviewer that David could have been white, Black or yellow: “In terms of what happened to him, none of that mattered at all.”

But neither did I realize that my love for the novel might communicate anything about whom I loved. David is gay and Baldwin was gay, so my mother’s response was hardly surprising. But the story is not, strictly speaking, about being gay. Baldwin called “Giovanni’s Room” a book about “what happens if you are so afraid that you finally cannot love anybody,” and that is as true a description of me as a teenager as any I could hope to find.

My youthful state of romantic insecurity is not the subject of this essay. But I think I would have encountered an altogether different Baldwin if I had first come across his name in a different context. He has been quoted on almost every anti-racist reading list in recent months. And if I had first found him on one of these lists, I would likely now view him as simply another fierce spokesman for Black America and enemy to white supremacy. He was both these things, but he was not exclusively these things, and I am convinced that interpreting him through so narrow a lens does a disservice to everything he can teach us about the problem of race and identity in American life.

I first connected with Baldwin because he taught me something about love, and that influenced everything that he had to teach me about color. He did not, of course, teach me about color through “Giovanni’s Room,” but rather through a series of letters to an America that, for all her toxic obsession with color, he could not help but love.

The Black Church and the Nation of Islam

Baldwin’s early years were spent in Harlem in New York City, where young “Jimmy” was born on this date in 1924. This was the Harlem of the projects, extreme poverty and race riots. His dad was a preacher and died when his son was 18. Jimmy entered the church as a 14-year-old and spent three years in the pulpit himself. His connection to Christianity forms the first half of the work for which he is most famous—a two-part essay called “The Fire Next Time”—and the background for his semi-autobiographical novel, “Go Tell It on the Mountain.”

The first work got Baldwin accused of being an assimilationist. The second got him accused of turning his back on the African-American experience. Both accusations amounted to the same charge: that he wasn’t sufficiently Black. The charge is based on the premise that there is such a thing as being Black—and that such a thing is worth protecting. He had many things to say about this premise.

The explicit subject of “The Fire Next Time” was Baldwin’s encounter with the Nation of Islam, the Black separatist movement that had attracted Malcolm X to its ranks, prophesizing that all white people were cursed and that Black people ought to have as little to do with them as possible. Baldwin’s piece was commissioned for Commentary magazine by the then-liberal Norman Podhoretz, who thought Baldwin would be able to understand “the growing appeal of Malcolm’s message” while holding out against its “pernicious ideology.”

Podhoretz detested the separatist ideology because he thought it “painted white people as the devil.” But in his essay, Baldwin noticed a deeper problem: that it painted Black people as God. “God is black,” they say. “All black men belong to Islam; they have been chosen. And Islam shall rule the world.” White people are immune from virtue and Black people immune from sin. “The dream, the sentiment is old,” Baldwin wrote. “Only the color is new.”

This was not a problem limited to the Nation of Islam. The same destructive pride seemed to dog the Black church of Baldwin’s youth. Nothing exemplified this more than when a minister told him never to give up his seat on a bus for a white woman: “What was the point, the purpose, of my salvation,” Baldwin asked, “if it did not permit me to behave with love toward others, no matter how they behaved toward me?”

The church seemed to suggest that there was a special place in heaven for people who shared Baldwin’s skin color, that Black Americans’ love for the Lord could be measured by their fear and distrust of white Americans. But for Baldwin, this was a myth—just as the idea of a Black Muslim world order was a myth and the idea of a flawless, freedom-loving American nation was a myth. All were masks “for hatred and self-hatred and despair.”

The Black Experience

But just as Baldwin feared the manifestations of a Black ethnic politics, he had a deep love for the bond that such a politics had formed:

In spite of everything, there was in the life I fled a zest and a joy and a capacity for facing and surviving disaster that are very moving and very rare. Perhaps we were, all of us—pimps, whores, racketeers, church members, and children—bound together by the nature of our oppression.

Baldwin recognized that collective struggle had given rise to a collective Black experience, with a legacy—political, intellectual, spiritual and artistic—that ought to command deep pride. This tension was characteristic of Baldwin, and it is part of the reason he has been read in so many different ways. He was accused of being an assimilationist, but he was also accused of being a militant who refused to recognize the racial progress that occurred during his lifetime. He never personally identified with the “integrationist” label, no matter how many times it was thrown at him. And in 1969, on “The Dick Cavett Show,” after his role in the civil rights movement had pushed his politics further and further left, he went so far as to tell a predominantly white television audience that the pursuit of integration was equivalent to white supremacy.

Indeed, Baldwin’s refusal to label white people in blanket terms was always paired with an insistence that America was covered by a blanket of racism. Though he disagreed with the separatist project, he thought Malcolm X was right to point out that when it came to violence, there was one standard for white people and another standard for everyone else. “The real reason that non-violence is considered a virtue in Negros” is that “white men do not want their lives, their self-image, or their property threatened.”

Baldwin was not an integrationist because he did not want Black Americans to be integrated into a burning house—and America had, as he saw it, been burning since its beginnings. “I cannot accept the proposition that the four-hundred-year travail of the American Negro should result merely in his attainment of the present level of the American civilization.” Rather, Americans needed new standards for how to live, and Black Americans were the key to finding them: “The price of this transformation is the unconditional freedom of the Negro. . . The American future is precisely as bright or as dark as his.”

Sixty-six years earlier, in an essay called “The Conservation of Races,” the Black intellectual W. E. B. Du Bois had articulated a similar-sounding message on a global scale. He argued that the Black race had “not as yet given to civilization the full spiritual message which they are capable of giving”—that the Black race had unique and particular strivings that, properly expressed, would “help to guide the world nearer and nearer toward that perfection of human life for which we all long.” In Du Bois’ view, race was not an artificial construction; the different races—including the Black race—would each make unique contributions to a pluralistic civilization.

Unlike Du Bois, Baldwin did not think that the contribution Black people could make to the American project had anything inherently to do with the fact that they were Black. “I have great respect for that unsung army of black men and women” in American history, he wrote. However, “I am proud of these people not because of their color but because of their intelligence and their spiritual force and their beauty.” His objection to the integrationist project was that it presumed America could go unchanged, and the country simply needed to incorporate Black people into a society that had been formed by slavery.

But his objection to the separatist project was that it presumed that a new, altered American society ought to be consolidated along racial lines, too. “As long as we in the West place on color the value that we do,” he wrote, “we make it impossible for the great unwashed to consolidate themselves according to any other principle.”

Baldwin did not want a white nation, and he did not want a Black nation. He wanted to build a nation that was neither white nor Black, a nation of individuals who were more concerned with what lay inside each other’s skin. This, he argued, could only be accomplished in America.

Baldwin loved America in the same way that he loved himself: fiercely, relentlessly—and, most of all, critically. Contained within American terror was a magnificent potential, a potential that would never be fulfilled by reifying the categories of color that had trapped it in racial hierarchy since its birth. Hence, racial progress needed to recognize the political reality of skin color—and the suffering it would continue to bring—while insisting that “the value placed on the color of the skin is always and everywhere and forever a delusion.”

This demanded a magnanimity from Black people that could hardly be justified by African-American history. Yet it was, Baldwin saw, the only way Black people could seize their own freedom in a country that had never previously accepted them. Black and white people alike had to, like lovers, see the tremendous boundaries that lay between them for the artificial constructions that they were. “I know that what I am asking is impossible,” he wrote. “But in our time, as in every time, the impossible is the least that one can demand.

Identity Beyond Race

As a young man, Baldwin began to “suspect that white people did not act as they did because they were white.” Understanding the real reason quickly became his key to solving the problem of race in America. After achieving literary success and finding himself in social circles that so many of his Black friends had envied, he began to form an answer. While he dined with Margaret Mead and partied with Norman Mailer, he realized that this predominantly white world was not different—at least, not essentially different—from the world he had known at home in Harlem. In an essay from his 1961 collection, “Nobody Knows My Name,” he puts it this way:

It seemed different. It seemed safer . . . cleaner, more polite, and, of course, it seemed much richer from the material point of view. But I didn’t meet anyone in that world who didn’t suffer from the very same affliction that all the people I had fled from suffered from and that was that they didn’t know who they were.

The final sentence is clunky, inelegant and uncharacteristic of Baldwin’s prose. But that is because he is hitting upon a truth that fails to fit the neat, coherent medium of polemic. He goes on:

Very shortly I didn’t know who I was, either. I could not be certain whether I was really rich or really poor, really black or really white, really male or really female, really talented or a fraud, really strong or merely stubborn. In short, I had become an American. I had stepped into, I had walked right into, as I inevitably had to do, the bottomless confusion which is both public and private, of the American republic.

The American race problem was a peculiarly American problem because America had used race to make up for something absent in its personality. Baldwin wrote these words in Paris, where he had moved in 1948 to escape America, and the experience had enabled him to create an individual identity beyond his Blackness. But doing so also made him realize that he would have no choice but to return to America, for America—and the question of race in America—was the “central reality” of his life.

When Baldwin wrote about the Harlem projects in “Nobody Knows My Name,” he added a paragraph on the “social and moral bankruptcy” of the white slums nearby. And when he wrote about poor Black people in a 1960 essay “Nothing Personal,” he made a point of mentioning the “poor whites” who were “enslaved by a brutal and cynical oligarchy” and had far more in common with their Black brothers and sisters than with wealthy white people. The racial tensions that menace Americans today,” he concluded in “The Fire Next Time,” are “involved only symbolically with color.” Indeed, “the question of color, especially in this country, operates to hide greater questions of the self.”

There was, according to Baldwin, a spiritual problem lying at the heart of racism in America: Individuals in America did not know who they were, and, as a result, the American republic did not know what it was. White Americans looked to the world for an identity, and they obscured the question with a series of myths about the Founding Fathers. And now that Black Americans wanted an identity for themselves, white America did not know how to respond. For Baldwin, both these pursuits were bound to fail because any attempt to achieve an identity as a collective was destined to fail. The world does not grant anyone an identity, he argued. Each person must find it for himself.

It has always been much easier . . . to give a name to the evil without than to locate the terror within. And yet, the terror within is far truer and far more powerful than any of our labels.

The Power of Love

Baldwin saw that the political could not be detached from the personal. If America were to move beyond the concept of race, then the concept of race would have to be eliminated from individual hearts. That could be accomplished only with love, for it was love that would allow people to seize their own freedom and build their own individual identities. As he put it, “people who cling to their delusions find it difficult, if not impossible, to learn anything worth learning.” The delusion that America is a free society disguises the fact that it has produced a population of unfree individuals. A people under the necessity of creating themselves must examine everything: Public and private life were intertwined, just as love and politics were intertwined.

If people could not talk honestly across the artificial boundaries of color, then it would be impossible for them ever to talk about these questions of love and death. “Our failure to trust one another deeply enough to be able to talk to one another has become so great” that “we are a loveless nation.” This was not a political point, but a metaphysical one. Baldwin sought to show that the stain of racism in America had entered his soul and that his soul had been strengthened by confronting that stain. “A country is only as strong as the people who make it up,” and Americans were not very strong at all. This is what led Baldwin to say that “civilization lives first of all in the mind.”

But Baldwin was ultimately hopeful—he was a preacher’s son, after all. He believed that American identity could be born anew, but only if Americans could come to terms with their history. This did not require shame but unbounded love. America was spiritually cold, and it needed to be made warm. “The Fire Next Time” was addressed to his Black nephew, and he told the young boy that he needed to love his oppressor:

The really terrible thing, old buddy, is that you must accept them, and I mean that very seriously. You must accept them and accept them with love, for these innocent people have no other hope. They are in effect still trapped in a history which they do not understand and until they understand it, they cannot be released from it.

Baldwin never gave “The Fire Next Time” to Podhoretz. He gave the manuscript to The New Yorker, and Podhoretz called him fuming a month later. They arranged to meet for a drink, and Podhoretz accused him of profiting from white liberal guilt and told him stories about his childhood encounters with Black thugs. “You,” Podhoretz said to Baldwin, “have told us that all blacks hate whites, and I am here to tell you that all whites are twisted and sick in their feelings about blacks.” Baldwin responded by telling Podhoretz to turn his monologue into a piece. The essay became “My Negro Problem—and Ours,” the most famous piece ever published in Commentary.

Baldwin wanted Podhoretz to write the article because he wanted Black people to know how white people felt. He wanted an open society, not a closed society, to free Black Americans, not coddle them. Baldwin despised arguments that explained Black people’s actions as an outcome of white choices—because if anything, he thought that the truth was more frequently the opposite.

It is the same repugnance for infantilization that led him to grow increasingly frustrated with his one-time mentor, Richard Wright. Wright was 16 years Baldwin’s senior and, at that time, the most famous Black writer in America. It was Wright who was Baldwin’s first Black hero, and it was Wright who first read Baldwin’s work and recommended him for a writing grant. Baldwin admired Wright and continued to admire him, but he also became increasingly frustrated by him.

While they were both living in Paris in 1948, Wright hatched a plan to form a pressure group that would force American businesses there to hire Black workers on a proportional basis. Baldwin disliked the idea but went along to the first meeting anyway. That evening, Wright made a speech that struck Baldwin as “mightily condescending.” He told the room full of Black men that some famous white people—including Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir—had wished to join, but that he had told them not to. They had to wait until he—Wright—had properly “prepared” the Black men to “receive” them.

There was, Baldwin thought, something quite funny about this episode, but also something distinctly unfunny about it. “I wondered what the probable response would have been had Richard dared make such a statement in, say, a Negro barber shop: N—, I been receiving white folks all my life. . . . Who you think you’re going to prepare?”

Wright’s line seemed to carry with it the implication that white people needed to tread carefully around Black people, that the Black man was somehow incapable of fending for himself. But Baldwin did not want special treatment; he did not want white people to do him or his fellow African-Americans any favors. He wanted only equal treatment; he wanted the white man to take his foot off the Black man’s neck.

Perennial Problems: Policing and Education

One area in which white oppression threatened Black men was the criminal justice system, so it is not difficult to see why Baldwin had complex views about the police. Several of his novels cover unjust cases of incarceration: Black livelihoods torn to pieces by prison time for no other reason than the racism of white police. He often remembers how he was abused—racially and sexually—by cops himself, and he repeatedly explains his contempt for a justice system that systematically persecutes Black men for crimes they did not commit. “I do not claim that everyone in prison here is innocent,” he wrote, “but I do claim that the law, as it operates, is guilty.”

Yet Baldwin also attempted to understand the average cop in the ghetto. He said the police officer is in general “good natured, thoughtless . . . innocent . . . facing people who want him dead through no fault of his own.” He represents the “force of the white world,” and he “moves through Harlem, therefore, like an occupying soldier in a bitterly hostile country.” He is not prepared for the revolution he finds on the streets, and he retreats into a callousness that quickly becomes second nature, resulting in a vicious cycle of police violence and youth violence.

There was no easy solution to this problem, but for Baldwin, any solution would need to fight on multiple fronts. It meant training decent, humane police who lived in the neighborhood. But it also meant an overhaul of the ghetto because its structure was “an irresistible temptation to criminal activity”—and more police enforcement against crimes committed by Black people against Black people, which had never been taken seriously. It meant more work and study programs, everything from hot lunches to academic courses in high schools, and it also meant helping Black people change the aspects of their own behavior and culture that were counterproductive to their own interests. None of these beliefs struck Baldwin as contradictory.

Like policing, education was and remains an area ripe for reform. As Baldwin began to teach at universities across the country, he saw firsthand that much of the elite discussion about race relations was oblivious to the reality facing most Black people—particularly working-class Black people—on the ground. In a late essay titled “Dark Days,” he wrote about his experience teaching at Bowling Green State University:

One of my white students, in a racially mixed class, asked me, ‘Why does the white hate the n—?’

I was caught off guard. I simply had not had the courage to open the subject right away. . . . The subject, I confess, frightened me, and it would never have occurred to me to throw it at them so nakedly. But once the matter was out in the open, the students began to talk openly.

They began talking to one another, and they were not talking about race. They were talking of their desire to know one another, their need to know one another. . . . They were trying to put themselves and their country together.

They did not discuss race because they no longer cared about race. Where their skin lay on the color spectrum was as irrelevant to their conversations as the number of hairs on their head. The students were repulsed by racism but did not express it by acting as though race was destined to dominate their lives. Nor did they set down rules for interracial dialogue. If they were going to get to know each other, they needed to understand each other. “In order to have a conversation with someone you have to reveal yourself,” Baldwin wrote, many years earlier. “In order to have a real relationship with somebody you have got to take the risk of being thought, God forbid, an oddball.”

In our current racial discourse, being thought an oddball—or, God forbid, wrong—is more and more frequently avoided at all costs. One is either racist or anti-racist, white or Black, with us or against us, an ally or an enemy. Thinking about one’s “privilege” is a task reserved only for certain people. And for those who are asked to turn inside and question themselves, they are told to make every effort to keep hidden what they find.

But Baldwin’s work continues to resonate, 34 years after his death, because he saw that politics could be conducted only by equal participants, just as two lovers could build a relationship only by opening their hearts on equal terms. He did not present himself—or Black people as a group—as innocent, nor white people as guilty. He tried to do something more honest. He tried to show that he, other people and therefore America were a mixture of both.

How to Move Forward

In 1998 The New York Times published a critical review of Baldwin’s work that argued he was an absolutist looking for a moral cataclysm that would never come. “Despite living through a wrenching, altogether extraordinary social revolution, he forever was tormented—cursed. Little wonder he lost his audience: America did what Baldwin could not—it moved forward.”

If the events of recent years have proven anything, it is that America has not truly moved forward. The election of a Black man as president did not move America forward, for it did not fundamentally change the living reality for most working-class Black Americans. There was no revolutionary cataclysm, no catharsis. America’s racial wound has never fully healed.

But realizing this has led some individuals to elevate the role that skin color plays in society. These self-described anti-racists sacrifice the pursuit of opening hearts to denounce closed minds, setting purity tests for what counts as Black opinion and thereby essentializing our notion of whiteness. As they label every institution eternally and systemically racist, they lose the plurality of individual perspective in favor of a frivolous chauvinism, papering over the stubborn influence of race and class in American society with the language of diversity and inclusion.

America is what it is, and it is impossible to change its history. It can be fixed, but it is not going to be transformed. But if we are looking for cataclysm, as our current moment suggests, then we must recognize the difference between one that fetishizes racial boundaries and one that seeks to move beyond them. We must ask whether a proper reckoning with racial history ought to lead us to embrace the concept of race or if we need to strive for something that comprehends the tangled, messy realities we subscribe to—a liberalism that, as the writer Thomas Chatterton Williams put it, “while pushing America to equal its ideals, soberly recognizes the harsh and irreducible realities of who we are.”

Politics is a game of competing stories about national identity. And today, too many people are trying to tell a shallow story. James Baldwin did not tell a shallow story. Nor did he tell a black-and-white story. Rather, he asked people to discover an entirely new story: We made the world we’re living in and we have to make it over.

To speak in my own person, as a member of the nation’s most oppressed minority, the oldest oppressed minority, I want to suggest most seriously that before we can do very much in the way of clear thinking or clear doing as relates to the minorities in this country, we must first crack the American image and find out and deal with what it hides.

In Baldwin’s words, “Afro-American” is a wedding of two confusions, “an arbitrary linking of two undefined and currently undefinable proper nouns.” “What passes for identity in America is a series of myths about one’s heroic ancestors,” he wrote. But what is actually meant by the term “African” is similarly obscure.

Our current stories are too simple, our labels too rigid and our hearts too closed to the contingency of our histories. Creating a new national identity means confronting the horrors that we face as a collective and finding what we have in common, emphasizing the promise of America and the potential love that lies deep within it. What Baldwin teaches about color is that it pales in comparison to the power of love, that a superficial attribute such as race does no justice to the complexity of the self.

No one in the world—in the entire world—knows more—knows Americans better or, odd as this may sound, loves them more than the American Negro. This is because he has had to watch you, outwit you, deal with you, and bear you, and sometimes even bleed and die with you, ever since we got here, that is, both of us, black and white, got here—and this is a wedding. Whether I like it or not, or whether you like it or not, we are bound together forever. We are part of each other. What is happening to every Negro in the country at any time is also happening to you. There is no way around this. I am suggesting that these walls—these artificial walls—which have been up so long to protect us from something we fear, must come down. I think that what we really have to do is to create a country in which there are no minorities—for the first time in the history of the world. The one thing that all Americans have in common is that they have no other identity apart from the identity which is being achieved on this continent.