Walmart Didn’t Kill the Small Town, It Is the Small Town

Big-box retail’s secret is not its car orientation but its (indoor) car-free urbanism

Last year, I was in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, helping a relative move into college. We made several obligatory Walmart stops, with all of the traffic-choked, 15-minute one-way drives that entails in the vast suburbs between the Research Triangle’s core cities.

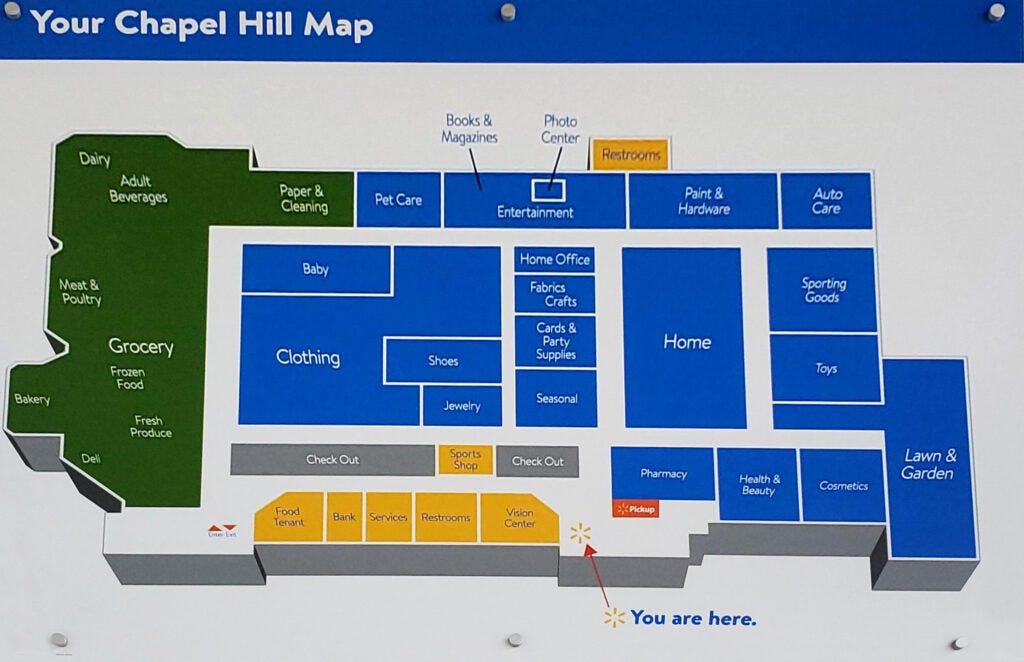

I don’t remember how many hours I’d spent in the car, but at one point I looked up at the store map in the Walmart lobby, and it struck me like an SUV barreling down the highway outside.

Does this image look like anything to you?

It looks a bit like this to me.

And not just this picture, which is Chapel Hill’s historic downtown core, courtesy of Google Earth. I mean in general. The interior of a Walmart looks like the street grid of a classic small town.

Downtown Chapel Hill is much bigger than a Walmart. But nonetheless, the relatively small Walmart in the city’s outskirts would fill about a third of the downtown’s busiest commercial block right off campus. In my hometown of Flemington, New Jersey—with a smaller downtown and a larger Walmart—the store would fill more than half of the old commercial core. The largest big-box superstores approach or exceed 200,000 square feet, which is about the size of a very small classic downtown.

The idea of a commercial space aping the design of a city is somewhat familiar when it comes to the suburban shopping mall. Malls were famously designed after urban downtowns or shopping districts by the European-born architect Victor Gruen, who envisioned them not as churches of consumerism but as weather-free, and traffic-free, diminutive cities.

It’s the traffic-free that especially interests me. The mall, as a collection of stores connected by “streets,” looks and feels like a commercial abstraction of a city. There is an echo of the glamor of urban downtowns in their heyday, with the department store serving as a link between the two forms. While an ordinary person might not think, “The mall is sort of like an indoor city without cars,” that appeal isn’t very far below the surface.

The big-box discount store, on the other hand—with its exposed steel ceiling, utter lack of ornamentation and warehouse atmosphere—makes no pretensions. You might go to the mall to take a stroll, or for a taste of elegance; you go to Walmart when you run out of milk or need kitty litter, as well as for the low, low prices. So it is striking that even in such a utilitarian setting, and such a quintessentially suburban one, the old urban DNA still survives.

This is not just a curiosity or a bit of trivia. We all know the why of Walmart’s destructive competition with small businesses. We might argue over whether big-box retail represents efficiency and progress, or concentration of economic power. Perhaps it is both. But almost everybody agrees that a store like Walmart is cheap and convenient, compared to the old model of going into town and patronizing a number of distinct and separate enterprises.

But the how of this process, which contributed to the desolation of numerous American Main Streets, is about more than just low prices and logistics and computerized inventory control. Walmart’s various business innovations were and are important, and many are now industry standards. But the conceptual core of Walmart is about design.

Walmart didn’t just compete with the small town. Maybe it didn’t exactly compete with it at all, per se. Rather, it replicated it. And, in stripping the frills and ornamentation of the indoor mall, it managed to replicate it quickly, cheaply and at scale. And so what the big-box discount department store effectively did was consolidate and transpose almost every classic Main Street enterprise—clothing, toys, crafts, decor, electronics, hardware and groceries —and place them all under one roof, under one corporate enterprise, in a massive, car-oriented property on the edge of town.

That map of the Chapel Hill Walmart resembles a town not only in a land-use sense—its “stores” and “streets”—but also in a business sense. Nearly every department—shoes, toys, pharmacy, etc. —represents what would once have been an independent specialized store. More than physical size or market share, this is the real sense in which Walmart has consolidated economic power.

But about that “traffic-free” bit: By segregating the cars completely outside and making the “streets” car-free—something often deemed suspect or radical when attempted in actual cities—the shopping experience becomes safer and more convenient to the customer. The ease of strolling down the “block,” crossing the “street” whenever you like, popping into whichever “store” you want, not worrying that kids will run off and get run over —those are the key conveniences of the mega-store. The essence of suburban big-box retail is classic car-free urbanism. Put it this way: If we could transpose the commercially vibrant walkability of a modern Walmart back to the downtowns it killed, those towns would be better off. They would, essentially, be their old selves.

This suggests that, despite the political framings and stereotypes around transportation and land use issues, the desirability of commerce in a walkable setting transcends political lines. Shorn of its urban setting and context, we don’t even realize we are doing it. The American small town—itself just one version of a nearly universal pattern—lives on, in some sense, in the very enterprises that helped destroy it.

Between the hidden urbanism of big-box retail and the numerous tax breaks, incentives and subsidies that such enterprises wheedle out of local governments, one can imagine a pro-market argument for favoring a more distributed kind of commerce in classic cities and towns. Is there really a free-market imperative to let chains build ersatz private downtowns, stripped of their fundamentally civic and public nature? Likewise, is there one to favor a business that isn’t amenable to coexisting economically with the community in which it is located, or to tear the web of local commerce in deeply settled places, and in turn diminish the opportunity for ordinary people to participate in entrepreneurship?

If the big-box superstore has preserved the land-use element of the classic town, it has jettisoned its distributed and participatory economic element, leaving in its raft of departments, some of the form but none of the substance of a real Main Street economy. Maybe the people wanted it this way. After all, they vote with their feet and their wallets. Maybe they’re voting for low prices uber alles. Or maybe they’re voting for car-free walkability. And if they are, maybe we should give the people more of what they want.