Ukraine and the Challenge to the Pax Americana

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine gives the U.S. a chance to rethink and reset its role as the leader of the Western democracies

By David Stier

Armed men in the streets, refugees fleeing fire and slaughter, and an outnumbered defense force fighting desperate holding actions. Such scenes are common in everyone’s newsfeeds these days from Kyiv to Kharkiv, and Mariupol to Mykolaiv. They were also common in 410, the year the city of Rome was sacked by the Goths and Huns, bringing a final end to the Pax Romana, or Roman peace, which had lasted since the time of Christ.

The next 1,400 years featured myriad wars in Europe as all sorts of powers, big and small, well-organized and less so, struggled for dominance. This struggle for order is again a major issue as Russian tanks and helicopter gunships rend Ukraine, an unprecedented and shocking break from the post-WWII order. While the tactical situation in Ukraine remains unresolved, it is clear that this unprovoked, large-scale, aggressive war of choice will have profound implications for world, and therefore American, security going forward.

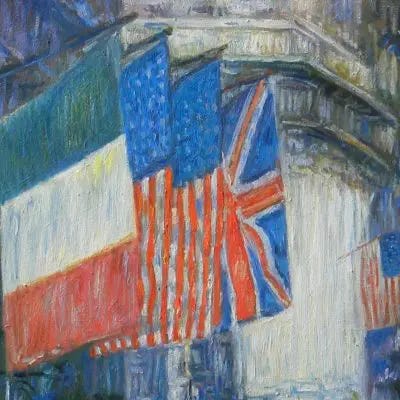

After the final defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815, a long period of peace and economic growth, underwritten by the British navy, ensued. The Monroe doctrine was a corollary of this protection umbrella. Democracy slowly radiated outward: For instance, France established the 3rd Republic in 1871 and even in Imperial Germany some power devolved from the Kaiser to the Reichstag. This Pax Britannica lasted until the Guns of August tragically sounded in 1914. What followed was a long period of conflict from 1914-1945, bookended by two world wars and that ended with the United States replacing Great Britain as the Western guarantor, or “hegemon,” of international order.

While the Cold War was certainly a central feature of the post-WWII period, the 77 years from 1945 until 2022 were also a period of largely uninterrupted, worldwide economic growth. The U.S. benefited tremendously from this arrangement. With developed countries such as Japan, Canada and France as allies around the world, the theoretical notion of “the West” took shape slowly, something that was mostly seen as an ideological alternative to Soviet communism. While there certainly was conflict, there were few wars between developed countries. The bedrock principle of this international order was that borders could no longer be changed by force, a major change in paradigm relative to the long sweep of history.

This principal was tested by Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990. However, President George H.W. Bush memorably declared, “This will not stand.” The ensuing deft American marshalling of widespread international support, coupled with the robust multilateral military action of Desert Storm, provided a devastating rebuke to this aggression and reinforced the principle that wars were just no longer acceptable as a tool of foreign policy. The Pax Americana, though tested, held.

Which brings us to the present moment. By any reasonable international and historical standard, the attack of Vladimir Putin’s Russia upon Ukraine is unprovoked. Ukraine presented no military or economic threat to Russia itself. Rather, President Putin allowed himself to fall in thrall to irredentist visions of a reconstituted Soviet Union. It was also a chance to eliminate a neighbor that was slowly building a democratic and free society atop its old Soviet foundation and setting an example that Putin did not want his own people to emulate.

Putin also saw the attack as a way to both take immediate advantage of perceived American decline after Afghanistan and German disorganization after the exit of its long-serving Chancellor Angela Merkel from the world stage. He perceived a time-limited window of opportunity and made the fateful decision to jump through it. This attack, shocking though it is, represents the latest step in Putin’s 15-year policy of destabilization and enmity for America and the West. It's also the most serious challenge yet to Pax Americana.

The political history of Russia over the last four centuries can be characterized as a long flirtation with Europe and the West. Beginning with Catherine the Great in the 18th century, Russia was considered one of the Great Powers of Europe, a group typically including Great Britain, France, Imperial Austria-Hungary, Prussia and then Germany. Czar Alexander played the key role in checking and ultimately defeating Napoleon, whose final exit ushered in said Pax Britannica.

However, Russia remained underdeveloped financially and politically throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. Many historians see the classic Russian focus on territorial expansion instead of internal development as a major weakness. Unlike many of the nations of Western Europe, the country’s railroad network was not extensive and, until 1861, indentured peasant serfs were a feature of rural life. And while most Western European countries and the U.S. were developing constitutional monarchies or republican forms of government, almost all power in Russia remained concentrated in the hands of the czar himself.

This creaky system proved to be no match for the shock of the Great War and the Communist revolution of 1917. Despite a large loss of life and much suffering in the years immediately following the revolution, Soviet Russia had rejoined the ranks of the Great Powers by the 1930s. The Soviet Union also suffered horribly during World War II (incurring perhaps 20-25 million deaths, many orders of magnitude more than those suffered by the U.S. and Britain) but emerged from the conflict even stronger—at least for a time.

Of course, the Soviet Union eventually collapsed in 1991, leading to a decade of social and economic chaos. And although the economy and society stabilized in the mid-2000s, the Russian people remain extremely fearful of a return to these conditions, possibly the most significant reason for Putin’s domestic popularity over time. Russians place great stock in stability. However, their economy remains poorly diversified—relying largely on energy production—and suffers from a lack of global competitiveness.

Until their unilateral seizure of Crimea and parts of the Donbass in 2014, there was a clear path to the West available to Russia. Relations with American and Europe at many levels, while never warm, were extensive. Many European countries saw economic opportunities in still underdeveloped Russia. Moreover, Russia had functional ties to NATO itself, setting up in 1997 a NATO-Russia Permanent Joint Council and even conducting joint military air exercises in 2011. Indeed, it was not unreasonable that Russia could eventually become a full-fledged NATO member itself, as well as joining the EU. This could have potentially been a great fit for everyone involved and the crowning moment for the triumph of the West. Fatefully, Putin turned Russia away from this path.

Domestically secure, Putin increasingly focused on restoring some measure of the raw power and influence of the Soviet Union to Russia, for reasons that seem less than rational. He partially dismembered distant Georgia in the Caucuses in 2008 before brazenly seizing Crimea in 2014 in a coup de main. Meanwhile, domestic dissent was increasingly strangled through one means or another. Many of these moves achieved Putin’s desired results, while frequently leaving the West divided with respect to how to properly respond.

However, it is hard to see how all of this actually helps Russia in the long term. Putin is a master tactician, adept at playing the cards he has through bluff and bluster. But he is a poor strategist. Suppose he had conquered Ukraine in days with relatively little bloodshed, as he clearly hoped, and many had predicted? Such an acquisition still brings little real benefit for what would have been a substantial cost in sanctions. NATO would have still deployed substantial resources right to their eastern border and dramatically increased defense spending. Meanwhile, a likely insurgency would have made it difficult and costly to maintain control of the country.

Now, with Ukraine fighting the Russians to a standstill in much of the country and asphyxiating sanctions raining down, it looks like a catastrophic decision for Russia and her people. To counter the West’s response, Putin is tying Russia more and more tightly to China, a country with which it shares no historical or cultural affinity. Russia’s ties are in fact much stronger with the West, where it has traditionally looked for cultural inspiration and economic support.

Geographically, China is much closer to mineral-rich, unpopulated Siberia than Moscow itself is. Beijing can only view Moscow as an ally of convenience, a junior partner useful in distracting America and diffusing its military power away from the Taiwan Strait. After all, Russia’s economy is barely 1/15th the size of that of the U.S., and its population has been shrinking for decades.

In spite of these weaknesses, Russia may well bludgeon Ukraine into submission and occupy and rule much of the country, potentially for many years. So, what should be the response of America and its allies to this extraordinary act?

If there is one thing Republicans and Democrats agree upon, it’s that China remains America’s chief geostrategic challenge. From China’s point of view, Putin’s invasion has to be considered a disaster. First and foremost, the West is now more united—politically and even culturally—in a way that it has not been for some time. For the first time, Pacific countries such as Australia and Japan are getting directly involved with sanctions and support for a European matter.

And, going forward, Western countries, starting with the U.S., are almost certainly going to spend significantly more on defense. The implications of this are enormous for China as the river of support can flow both ways. Japan, South Korea and Australia are all now sending military equipment to Ukraine. It is no great leap to see European NATO countries reciprocating and helping to arm Taiwan. These developments will make Taiwan tangibly more secure.

Integrating a still-growing China into the international order without a third World War remains challenging. History indicates that this will not be easy, as the difficulties of integrating a rising Germany in the runup to World War l show.

In addition, there is no question that America is in relative decline with respect to the power it wielded perhaps 60 years ago during the time of President John F. Kennedy. However, the key word is relative. Indeed, America’s inherent advantages remain. Since the dawn of the republic, the U.S. has benefited immensely from the protection of vast oceans on both coasts. Yet oceans don’t always protect a country from missiles, let alone cyberattacks. But as the Ukraine crisis shows, it’s still better to be far from aggressors than sitting on their border.

The U.S. also continues to be the most important economic player in the world, with nearly a quarter share of the globe’s GDP. The American work ethic (3.8% unemployment rate and markedly higher GDP per person than other Western countries) and innovation (Google, Apple, Microsoft, etc.) remain best-in-class. America is now essentially energy independent, a huge advantage relative to the Cold War period. And the dollar is still the world’s reserve currency, which is the biggest reason American sanctions against other countries can be particularly effective.

The rule of law, a key underpinning of America’s economic success, also remains intact. In American towns and cities, with some exceptions, the police come quickly, will not attempt to extort a bribe, and will try to help rather than hurt you. This is not how it is across much of the non-Western world. In addition, strong property rights support investment and hence economic growth.

Finally, the U.S. still has many friends in Europe and Asia. An awakened Western-aligned Europe and Asia with dramatically higher defense spending and an expanded worldview can only benefit America.

The big challenge and opportunity are how to lock in the current renewed spirit of the developed countries long allied to America. Having strong American ally Germany step up and play a geopolitical role more commensurate to its economic heft is potentially game-changing. Dramatically increased defense spending from Portugal to Poland will have the net effect of allowing Europe to take over more of its own security needs, facilitating the long-desired American pivot to Asia.

A significant American presence must remain in Europe for deterrence and as a tangible symbol of trans-Atlantic fraternity. There is no longer any reason not to deploy NATO troops in strength right on the eastern borders—the Baltic States, Poland, Slovakia and Romania. Putin has brought this on himself. NATO must no longer be cowed by his threats (even nuclear threats) and bluster.

In the Pacific, the challenge will be to develop and cultivate increased European attention to the security situation there. Just as the invasion has united countries such as Australia and Japan to take concrete actions to support Ukraine, so must the continued Chinese saber rattling over Taiwan move NATO itself to take more of a concrete interest in the Pacific.

It will also be important to continue to formalize and deepen alliances in the Pacific. The “Quad” grouping of the U. S., Japan, Australia and India provides one path, although India’s standoffishness during this current Ukraine situation raises important questions as to their strategic thinking. Both Japan and Australia are taking more interest in their security, providing more opportunity. South Korea, with its newly elected, pro-American president, is also in the mix. However, security in the Pacific will also have a significant economic component.

While Taiwan is certainly threatened militarily, China aspires to best the U.S. economically. It will therefore be crucial for the U.S. to forge stronger trade relationships with like-minded allies worldwide, as well as continue to grow the American economy at home. Longer term, economic vibrancy is as much, if not more, a guarantee of national security than military prowess.

During the Pax Romana and Pax Britannica, the referenced peace applied essentially to the continent of Europe. The post-war Pax Americana is somewhat more global, but has specific characteristics in each of the Atlantic and Pacific zones respectively.

What needs to happen now is that this moment of worldwide clarity over Ukraine must be translated into a new “Peace of the West” or “Pax Occidua,” which would be fully global in scope attack on one is an attack on all. The nascent concept of “The West,” a group of countries sharing comparable development levels, respect for the rule of law, human rights and democracy, must take a more tangible form.

America no longer has the strength to do most of the heavy lifting for this new Western alliance, which is why others must step forward just as Germany seems to be doing now. And yet, it will still require substantial American leadership—diplomatic, military, economic and political—to create and sustain this new Peace of the West.

While relatively weaker, the U.S. remains uniquely positioned geographically, militarily and economically to play the leading role. No one else can. The alternative, with the developed democracies fragmented and isolated, would be much more insecurity and ultimately would require much higher defense spending from all. And it could lead in time to a catastrophic third World War.

Freedom isn’t free, but it isn’t just a question of money. Leadership is what is needed now, first and foremost, along with strength and clarity of purpose. Ukraine offers the U.S. and other Western nations a new opportunity to rise to the challenge and preserve the peace.