Town Meeting 101

New England’s preferred form of municipal governance shows how direct democracy can work in America

By Tim Czerwienski

Last year, Massachusetts enacted legislation requiring cities and towns to zone for greater residential density around transit hubs. Soon after, the state issued draft compliance guidelines, setting a deadline of December 31, 2023, for the 175 municipalities covered by the law to adopt a zoning district that allows multifamily housing by right. As Massachusetts cities and towns work to comply with the new legislation, outside observers may be perplexed by the terms and processes that are going to be coming out of the commonwealth in the next 18 months. While many U.S. cities and towns use a (relatively) straightforward system of a city council or a board of aldermen to amend bylaws or pass budgets, most New England municipalities have a different approach. If you want to understand the success or failure of zoning reform in Massachusetts, you need to understand Town Meeting.

Structure of Town Meeting

To put it simply, Town Meeting is the legislative body of most municipalities in New England. The term refers to both the body and the event at which that body meets. Here in the Bay State, Town Meeting is the predominant form of local government: Only 17% of its 351 municipalities have the more familiar mayor/manager-council arrangement. Massachusetts is where Town Meeting was born and where I’ve been a participant for most of my career as a public official, but the system is similar throughout New England. Town Meeting is responsible for approving a municipality’s budget and amending its bylaws. The traditional Town Meeting, dating back to the first English settlements in North America, is an open, Athenian-style affair. Unlike the mayor/manager-council form of government (in which citizens elect representatives to pass laws), the Town Meeting is a direct democracy: Every adult resident can show up, comment on the business before the meeting and vote.

There are guardrails, of course, that keep things from turning into a free-for-all. Town Meeting is administered by a moderator who acts as the meeting’s chair by managing speakers, entertaining motions, calling for votes and enforcing the rules. Town Meetings tend to follow some type of parliamentary procedure such as Robert’s Rules of Order (although in Massachusetts, some towns use a state-specific set of rules called Town Meeting Time). Discussion is limited to items that appear on the warrant (or the warning), which serves as the meeting’s agenda.

The warrant is a big deal, since it announces both when and where Town Meeting will take place, but also what will be up for debate. There are a multitude of statutes, bylaws and customs governing the assembly, review and distribution of the warrant. In general, several months before Town Meeting, the Select Board (a town’s executive body) will “open the warrant,” meaning that it will accept submission of articles to be discussed at Town Meeting. A town’s various boards and committees may submit budget articles, the Planning Board may submit articles to amend the zoning bylaw and the Select Board may submit articles to dispose of public land or accept easements. Groups of residents can also submit articles in what is known as a “citizen petition.”

When the Select Board “closes” the warrant, it often goes on to a separate committee—sometimes called a finance committee, an advisory committee or simply a warrant committee—which reviews and debates the various articles in public meetings to provide recommendations to Town Meeting as to how it should vote. Those recommendations are sometimes printed in a separate report, but they can also appear in the final warrant itself. The warrant must be made widely available to the public; each town sets its own bylaws for this, but they often include some combination of posting in multiple public places, publishing notices in the local newspaper and delivering to residents’ homes.

Rooted in History

Town Meeting’s colonial-era roots are clearly visible in all of this. In a small, tightly knit settlement populated by people who crossed an ocean to escape the authority of a powerful monarch, a meeting to collectively decide the group’s business was a logical way to govern—especially because the settlers shared the same culture, race and religion. Direct democracy spoke to the ideals of the early New England colonists. Recall John Winthrop’s famous description of the Massachusetts Bay Colony: “For we must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill. The eyes of all people are upon us.”

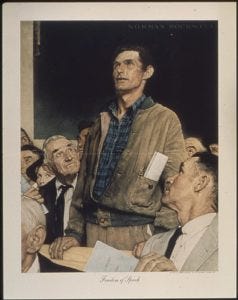

Norman Rockwell's "Freedom of Speech" depicts a citizen saying his piece at a Vermont town meeting. Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

If those eyes happened to fall on an early Town Meeting, though, they were likely to see an unruly, chaotic and sometimes drunken affair. The moderator was introduced by Chapter 244 of the Acts of 1715, which stated, “By reason of the disorderly carriage of some persons in the said meetings, the affair and business is very much retarded and obstructed. . . . Be it enacted . . . that at every such a meeting a moderator shall be first chosen . . . who shall be thereby empowered to manage and regulate the business of that meeting.” The Acts of 1715 also established the strict rule that Town Meetings could not vote on or decide any business unless it was in the warrant for that meeting, ostensibly to impose some measure of order and prevent Town Meetings from spiraling into tangential side discussions.

These rules, and many others, persist today. The sheer size of Town Meeting and the number of ancillary processes have consequences for how municipal business gets conducted. It’s one thing to assemble a quorum of seven city councilors on a regular basis to pass ordinances and set policies. It’s another thing entirely to gather hundreds of resident volunteers for a formal legislative session, and to prepare for such a session with months of additional public meetings and costly notice requirements. While it’s not uncommon for towns to hold a second Special Town Meeting in addition to the Annual Town Meeting to handle nonbudgetary matters, it’s very rare to see more than a handful of Town Meeting sessions in a single year.

Persistence of Town Meeting

Under the Town Meeting structure, towns have only one or two chances a year to change their zoning, appropriate funds, authorize bonding or do anything that requires legislation. So why do so many towns maintain such a seemingly inefficient form of government? Inertia is an obvious answer. Town Meeting has been the form of local government in New England for as long as New England has existed. In Massachusetts, both the General Laws and the constitution itself place strict limits on the circumstances and the process by which a town can change its Town Meeting form of government.

But inertia isn’t the whole story, because towns can and do change their form of government. Framingham, Massachusetts, with a population of more than 70,000, made the switch to a city structure in 2017. Towns with more than 6,000 residents can choose to adopt a representative Town Meeting, by which the town divides itself into precincts that then elect a limited number of people to represent them at Town Meeting. According to the Massachusetts secretary of state, “The total elected representative Town Meeting membership can be as few as 45 or as many as 240.” There are currently at least 36 representative Town Meetings in the commonwealth.

Town Meeting persists, in part, because it reflects the pride and sense of tradition that New Englanders claim to treasure. If you focus too much on the shambolic details of how warrant articles are written and debated, or compare the ponderous pace of Town Meeting to the relatively efficient mayor-council system, you miss the small miracle of history reaching into the present. Winthrop’s “city on a hill” may be a threadbare cliche at best—and at worst an obscene joke to those who have been excluded from that vision over the centuries—but New England Town Meeting remains America’s best and most effective form of direct democracy. As Michael Morrell, a University of Connecticut political scientist, said in a 2019 edition of the Journal of Public Deliberation, Town Meeting is both “participatory and deliberative” in a way that California-style referenda, or other high-profile forms of direct democracy, are not. Town Meeting is certainly more representative and robust than the quasi-democratic community meetings, comment periods and consultations that have come to adorn seemingly every major (and not-so-major) local, state and federal decision-making process.

When Norman Rockwell illustrated Roosevelt’s “Four Freedoms” in 1941, there was a reason his subject for “Freedom of Speech” wasn’t a newsroom or a soapbox polemicist, but rather an ordinary person standing up to say his piece at a Vermont Town Meeting. The idea that anyone can not only be heard, but actually play a meaningful role in governance, is at the heart of our national sense of self. In New England, Town Meetings are still trying to make it work the old-fashioned way.