Three Forces That Threaten Liberalism and How To Counter Them

By Emily Chamlee-Wright

Liberalism is the philosophical, moral and political system that begins with the presumption that we human beings—all of us—are one another’s dignified equals. From this starting point follows other liberal principles such as individual liberty, equal rights, the rule of law, toleration, intellectual openness and pluralism.

Economic historian Deirdre McCloskey observed that liberalism is the mother of the 3,000% increase in material abundance that the world has enjoyed over the past 2 1/2 centuries. Because liberalism acknowledged the dignity of the common person, it tapped humanity’s creativity, ingenuity and productive capacity, ushering in dramatically improved conditions, longer lifespans and more elbow room for economic, scientific and cultural experimentation. Liberalism shifted political control from a narrow band of autocrats and landed elites to a body of self-governing citizens. By supporting the open exchange of ideas, liberalism makes us partners in discovery and truth-seeking, which in turn pushes out the boundaries of knowledge and human progress.

Of course, liberalism in practice has never fully lived up to its ideals. But over time, those ideals have guided us toward greater freedom, equality and human flourishing.

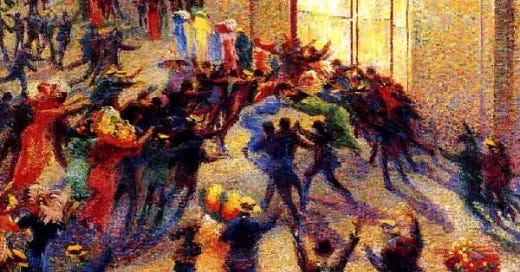

Now, we have good reason to worry that illiberalism is on the rise, globally and here at home. Countries once thought on a clear path toward stable liberal democracy—Poland and Hungary, for example—have taken a right turn toward blood and soil nationalism. China, which was once trending toward greater economic liberty and freedom of expression, has now moved toward iron-fisted authoritarianism.

Challenges from Each Side

While Americans have long been aware of the troubling presence of far-right extremism, conventional wisdom held that it was too much on the fringe to affect mainline 21st century political culture. Events such as the white nationalist rally in Charlottesville in 2017 and the storming of the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6 indicate that the conventional wisdom may be wrong. At the same time, far-left extremists have embraced violence on an alarming scale, with attacks on government buildings and business districts in Seattle, Portland and other cities over the past 16 months.

Liberalism faces challenges not only in politics but in mainstream academic and public discourse as well. Scholars and public intellectuals on both the left and the right have declared liberalism a failed project. Critics on the nationalist right reject liberalism’s openness to the world and its embrace of cultural change, calling instead for economic nationalism and tightened borders. Critics on the progressive left reject liberalism’s openness to the free exchange of ideas. And liberal guarantees of equality, they argue, will not suffice if we are to attend to pressing social justice concerns. Political and economic systems, they say, must be wholly reimagined and reengineered to ensure equal outcomes.

Not so long ago—around 1989 and the fall of the Berlin Wall—it felt as though liberalism no longer needed vocal defenders. It was presumed that the world’s nations were converging toward liberal democracy and its principles and institutions: constitutionally constrained government, the rule of law, protection of minority rights, an independent judiciary, a free press and so on. And whatever disagreements we might have had about the optimal level of economic regulation, these basic principles were the common ground on which most Americans stood. That common ground can no longer be assumed.

What, then, is required of us if we are to reconstruct the liberal project of universal human dignity, civil liberties, constraints on political power, toleration, pluralism, and intellectual and economic openness?

To reconstruct the liberal project we must name and reassert the liberal sensibility. By “sensibility” I mean—borrowing George Will’s definition—something more than an attitude but not quite an agenda. Reasserting the liberal sensibility is less about liberal policy reform and more about fortifying liberal cultural norms and intuitions, and a liberal intellectual tradition that supports those norms and intuitions.

The cultural heritage which contains the whole structure and fabric of the good life is acquired. It may be rejected. It may be acquired badly. It may not be acquired at all. For we are not born with it. If it is not transmitted from one generation to the next, it may be lost, indeed forgotten through a dark age, until somewhere and somehow men rediscover it, and, exploring the world again, recreate it anew.

—Walter Lippmann, “The Public Philosophy”

Walter Lippmann, 1905. Image Credit: Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons

What I have in mind is similar to what the public intellectual Walter Lippmann described as a “public philosophy” and what sociologists Robert Bellah and Phillip Hammond call a “civil religion.” I prefer the phrase “sensibility” because it connotes the space between the unquestioned faith of religion and the cold calculus of reasoned philosophy. The idea here is that by naming the liberal sensibility, we are better positioned to reassert it in our civic lives, and we begin to fortify the common ground that underlies the good society.

But why is a reconstruction necessary—why, despite its many virtues, does liberalism face such significant challenges and require a renewed defense?

For all the ways in which liberalism makes life more productive and peaceful, three powerful forces push against it, forces that I roughly categorize as tribalism, scientism and forgetfulness.

Hardwired for Tribalism

In our polarized times, it’s common to observe that our political discourse, civic lives, media echo chambers and even our residential patterns are increasingly tribal. We’re concerned that, increasingly, we seem to be at war with our fellow citizens. We seem to be losing our ability to be with, converse with, learn from and live peaceably among people who hold points of view different from ours. And it’s not merely that we disagree with the other side, it’s that we see their very existence as a threat to our own.

Clearly, when deployed in this way the word “tribal” is meant to describe something negative. But it’s worth understanding the role that tribalism has played in the 200,000-year history of human evolution. Tribal instincts enabled our early ancestors to survive, despite significant disadvantages. Compared with other mammals, our primitive ancestors were lumbering and slow. With no fangs, claws or protective hide, they were easy prey. But they had two things going for them: They had big brains and they had each other.

Their brains allowed homo sapiens to cooperate, divide and share tasks, and, most importantly, develop language. With language came culture and the ability to transmit meaning; create and share rituals of belonging, reciprocity and allegiance; and establish structures of authority. Bonds of family and band affiliation—the strong sense that there is an “us”—improved a group’s chances of warding off predators, securing food and other resources, and achieving victory in violent confrontations with other bands. Band affiliation, in other words, was the first known social-trust technology that human beings developed to overcome the collective-action problem of survival.

The hardwiring that made tribal affiliation possible and desirable hasn’t changed much. Our tribal instincts are still very much with us. What has changed, largely over the past 250 years (an evolutionary blink of an eye), are social innovations that have radically expanded the radius of trust, far beyond what was possible for our primitive ancestors. It’s the social institutions of liberalism—monetary exchange, property rights, rules of contract—that have expanded exponentially the number of people we are able to cooperate with. By shifting from personal to impersonal forms of trust verification, human beings have grown our circle of potential collaborators from dozens to millions of people.

Long-distance trade, for example, put our ancestors in direct contact with people who believed different things, worshipped different deities, looked and dressed differently. If their first tentative interactions worked out, they tried again, and eventually established patterns of inter-tribal trust. Fast-forward many generations and the descendants of two very different tribes may find themselves working together as colleagues or living together as flatmates or marriage partners. And each descendant of those early trust builders relies upon an intricate network of service providers, clients, product designers and manufacturers (who belong to countless other tribes) to live productive lives of abundance.

It’s not that liberalism eliminates our tribal impulses. What it does do is create a pathway by which we get the benefit of our tribal hardwiring without its damaging effects. We enjoy the rich, intimate sphere of an “us”—family, friends and community—without the anxious fear of a “them.” It gives us pluralism.

But this balance that brings about pluralism is not inevitable. It takes work to maintain, and if left untended, entropy takes hold and we are drawn back to the familiar and parochial. Further, liberal pluralism is vulnerable to the corrosive effects of political interests that feed off division. Authoritarian figures and populist movements exploit this vulnerability by provoking fear. They gain power by advancing zero-sum logic that the well-being of one group comes at the expense of the other; that one group’s survival depends upon the annihilation of the other. The ancient part of the human brain—the part that tells us to fight or flee when our threat response is triggered—makes us collaborators in the manipulation.

One need not look far—over the course of liberalism’s history or in our present moment—to find examples of cynical manipulation. What is new is the ease with which destructive “us vs. them” tribalism can be manufactured at scale. Malicious social media bots advancing false or hyperbolic claims, for example, are designed to trigger expressions of outrage on one side of the ideological divide, which in turn triggers outrage on the other side, fueling polarization and eroding social trust.

In short, one of the most important benefits of a liberal society is enabling us to peacefully co-exist with different people. But our grip on this is tenuous, especially when there are forces that benefit from its decline.

The Fatal Conceit of Scientism

In “The Counter-Revolution of Science,” F. A. Hayek popularized the word “scientism” to describe the inappropriate application of the methods of the natural and physical sciences to the study of human society. As he observed, unlike inanimate objects, human beings have purposes. In a world where uncertainty is ever-present, we seek, imperfectly, to understand and interpret our environment. We form expectations about the motivations and potential actions of other imperfect human beings. We identify ends and make educated guesses at how best to pursue those ends. We act, we learn, and based on that learning, we revise our expectations and act again, all the time changing the very environment in which we are operating. To apply the methods of the physical sciences to human society as if it were made up of billiard balls rather than meaning-creating, expectation-forming, interpreting beings with purposes of their own is, in Hayek’s view, an abuse of reason.

Scientism contributes to what Hayek described as the “fatal conceit,” the assumption that a rationally designed order is superior to an emergent order. The conceit is fatal, he argues, because when we attempt to override the social order that emerges from the bottom up with an intentionally designed order imposed from the top down, we crush the very process by which society learns and adapts.

Though Hayek’s target was socialism, scientism is also at work in contemporary debates about industrial policy. Economic nationalists on both the left and right argue that the U.S. economy has become vulnerable to the whims of foreign powers, leaving many American workers without meaningful and dignified work. The U.S. must “re-shore” global supply chains, they argue, and boost manufacturers through trade restrictions and government subsidies. Some scholars and intellectuals say the U.S. must restrict or reform immigration to preserve America’s culture and identity. In a similar vein, religious conservatives eschew what they describe as the corrosive effects of liberalism on the American family.

Such policies tend to go unchallenged because the self-regulating properties of complex social systems are difficult to comprehend. As Hayek observed, “The curious task of economics is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design.” We human beings have a hard time understanding the limits of human reason. Further, the negative consequences of social disruption will often be experienced more immediately than the order that emerges in its wake. In moments of disarray, the rational mind instinctively (and understandably) wants to deploy its faculties of reason and design to bring order to the apparent chaos.

But this is where we get into trouble. When we apply the principles of design, control and top-down authority to the extended order of the open society, we crush it.

The Problem of Forgetting

As Hayek observed, liberal institutions that make market order possible—private property rights and rules of contract—are not developed through reason. Rather, they are inherited culturally, often without a clear understanding of why the inherited practices convey the benefits that they do. It is not the police car on the corner or the cold calculus of cost and benefit that leads most people to conduct their affairs, most of the time, with honesty and integrity. It is the internalized sensibility that removes predatory behavior from the menu of options from the start. And through generations of enculturation, liberal norms become automatic, a matter of impulse.

Once a set of rules becomes an entrenched part of the culture, the impulse to “do the right thing” bypasses the need for deliberation. Sentiments, intuitions, norms, habits and attitudes create economies of scale for the institutions they support because they work regardless of whether people understand why they work. When moral sensibilities have been so internalized that we follow them without thinking, external monitoring becomes less necessary, thereby lowering the costs of rule enforcement. As the costs of rule enforcement drop, the benefits of rule-following become more widespread. We get more voluntary trade and less predatory behavior. Liberal intuitions, in other words, help liberal institutions take root and thrive.

But a liberal culture is vulnerable to the phenomenon of forgetting. When the right response, the just and honorable response, the peacemaking response, no longer requires deliberation, we no longer deliberate. And without deliberation, we can easily forget why those liberal impulses tend to lead to good outcomes, and that can lead to personal, civic and public policy decisions that undermine a liberal society.

One way out of the forgetting problem is enculturation, to tell ourselves and one another, for example, that “this is what God commands.” Parental, religious, civic and government authorities can bolster the auto-response with systems of reward and punishment. But when these traditional forms of authority break down, so too does the auto-response. When the question is asked, “Why must I follow this rule?” the answer, “Because this is what [Authority X] expects you to do,” no longer suffices. New cultural norms and intellectual rationales are required.

Reclaiming the Liberal Project

Clearly, policy reforms will be part of the effort to reclaim the liberal project. And there is no shortage of target-rich policy arenas where liberal reform is required.

The overcriminalization of daily life, for example, erodes respect for the law and undermines the principle of a rules-based society. The qualified immunity from legal consequences that protects police officers, prosecutors and others with power in the criminal justice system gives people reason to be cynical about the liberal promise that everyone will be treated equally before the law. Government-imposed barriers to entrepreneurial endeavor—from unnecessary occupational licensing at the lowest rungs of the economic ladder to industrial policy that picks winners and losers—serve to subvert market discipline, promote crony capitalism and impede liberalism’s ability to expand human well-being to an ever-wider span of society.

Reclaiming the liberal sensibility, however, transcends questions of public policy. A robust liberal sensibility that pushes against the forces of tribalism, scientism and forgetting will depend on cultural norms, intuitions and ideas. The ones that seem most relevant today include a default posture of optimism in the face of change, a healthy skepticism of power, an attitude of intellectual openness and humility, and an impulse toward toleration.

A default posture of optimism in the face of change and a healthy skepticism of power are especially important if we are to resist scientistic thinking that favors top-down solutions to complex problems. These defaults may manifest in a variety of ways, such as an attitude of calm curiosity and confidence in the throes of cultural or economic disruption. If we see the world through this lens, our default is to believe that social, cultural and economic processes have a way of working out, even though we don’t know exactly how they will work out.

Resisting Top-Down Control

But this lesson—that complex social systems have self-ordering properties—is not obvious. If the lessons of emergent-order thinking are to stick, and we are to resist the slide toward top-down authoritarian control, cultural intuitions that lean toward liberal solutions need intellectual grounding. Scholars, teachers and writers play an important role in bolstering the liberal sensibility by articulating the mental models that help us understand and anticipate the emergence of order out of economic and cultural disruption.

The economic way of thinking, with its emphasis on spontaneous-order processes, offers one example. Further, intellectual efforts—from well-developed bodies of thought such as public choice theory to dystopian fiction—help us spot the dangers of authoritarian control, even when they are offered by well-intended social reformers.

Similarly, a default posture of openness to new ideas and humility about what we know requires both intellectual and cultural grounding. J. S. Mill’s “On Liberty” helps us see how the free exchange of ideas weeds out error and sharpens our understanding of truth. But for liberalism to thrive, a working knowledge of Mill is not enough. We also need the enculturated habits of curiosity, honesty, and the presumption and practice of good faith. These are skills that are cultivated through practice and coaching by parents, teachers and colleagues. When inducting young scholars into an intellectual community—whether they are undergraduates, graduate students or new colleagues—greater attention must be paid to cultivating these habits. The same could be said for inducting citizens into civic life.

And if we are to resist the dangerous effects of “us vs. them” tribalism, toleration also requires both intellectual and cultural grounding. Only a tolerant society has the potential to become a richly pluralistic society. One can come to this understanding by way of direct experience. By engaging in cross-cultural commercial exchange, for example, we become familiar with one another. Through repeated interactions, baseline tolerance has the potential to turn into civic friendship. But as we live through it, the workings of this process can escape our notice. Knowing the history of how religious toleration in liberal societies developed into religious pluralism can bolster a cultural intuition that favors toleration more generally.

Liberalism Is a Journey

What is both promising and frustrating about liberalism is that it is more process than end state. As if on a journey where the destination is imaginable but not yet experienced, liberal principles serve as our compass. Having the liberalism compass is not the same as achieving the highest ideals of the liberal promise, but it is a powerful tool. It’s guided every wave of human progress we can point to in the past 2 1/2 centuries.

The problem is that the compass has been so present on our journey that we often forget it’s there. Especially as we face daunting challenges with respect to civil rights, barriers that impede economic opportunity, catastrophic disasters and global health crises, we need to remind ourselves that the compass is in our pocket. We need to pull it out, dust it off and use it.

By naming the liberal sensibility, we are better equipped to deliberately assert its principles. We draw attention back to liberalism’s highest ideals, that we are, for example, one another’s dignified equals. We remind ourselves that these commitments define what it means to be a good neighbor, a good parent, a good colleague and a good citizen.

If we name and call attention to the liberal sensibility frequently, it takes hold. It becomes a matter of impulse. If pressed, such impulses should withstand the scrutiny of interrogation. We could, if called upon, explain the intuition behind our liberal principles to our neighbors, our children, our colleagues and fellow citizens, and we would feel it our duty to do so. We begin, in other words, to rebuild the common ground that underlies the good society, a society in which pluralism, intellectual openness and dynamic innovation thrive.