The Spectacular Promise of Artificial Intelligence

AI has limits, but it could be the big breakthrough in productivity that we need

A few recent consumer-facing innovations—the ChatGPT chatbot and Lensa AI image generator—have brought public attention to a breakthrough moment for artificial intelligence.

The AI of our science fiction dreams and nightmares—complete with human-like consciousness and characteristics—is still a long way off. The real-life versions are a lot more prosaic, and the innovations hitting the headlines right now are still mostly toys that capture the public imagination, rather than productive tools.

But the progress in artificial intelligence is real and significant, and it prompts us to consider the enormous promise of this technology as it comes to maturity.

AI Is My Copilot

Our view of artificial intelligence has been distorted by techno-pessimism and the fact that we are more likely to encounter AI—at least in the forms where we recognize it—in dystopian science fiction rather than technological reality. So every generation has its stories about killer robots bent on destroying humanity. Depending on your age, it’s HAL 9000, the Terminator, the Matrix or maybe Ultron. Even the original “Star Trek,” with its optimistic view of the future and of technological development, had its share of malevolent AIs.

Meanwhile, philosophers generally haven’t helped us grasp the new technology, instead importing their own obsession with arcane philosophical puzzles like the “trolley problem.” So they ask preposterously premature questions about whether self-driving cars should swerve to run over a little old lady in order to avoid running over a child—at a time when self-driving cars still can’t reliably tell the difference between a person and a lamppost, much less between one person and another.

The reality of AI is very different. The one that has most recently captured the public’s attention is ChatGPT, a kind of autocomplete on steroids, where you give the computer a prompt and it generates text based on information it has previously gleaned from the internet. The chatbot’s phrasing and sentence structure are quite plausible, even if it often has persistent troubles with detail and accuracy. It can even compose simple poetic verse, more or less well. (See what happened when Virginia Postrel asked it to write some poetry.)

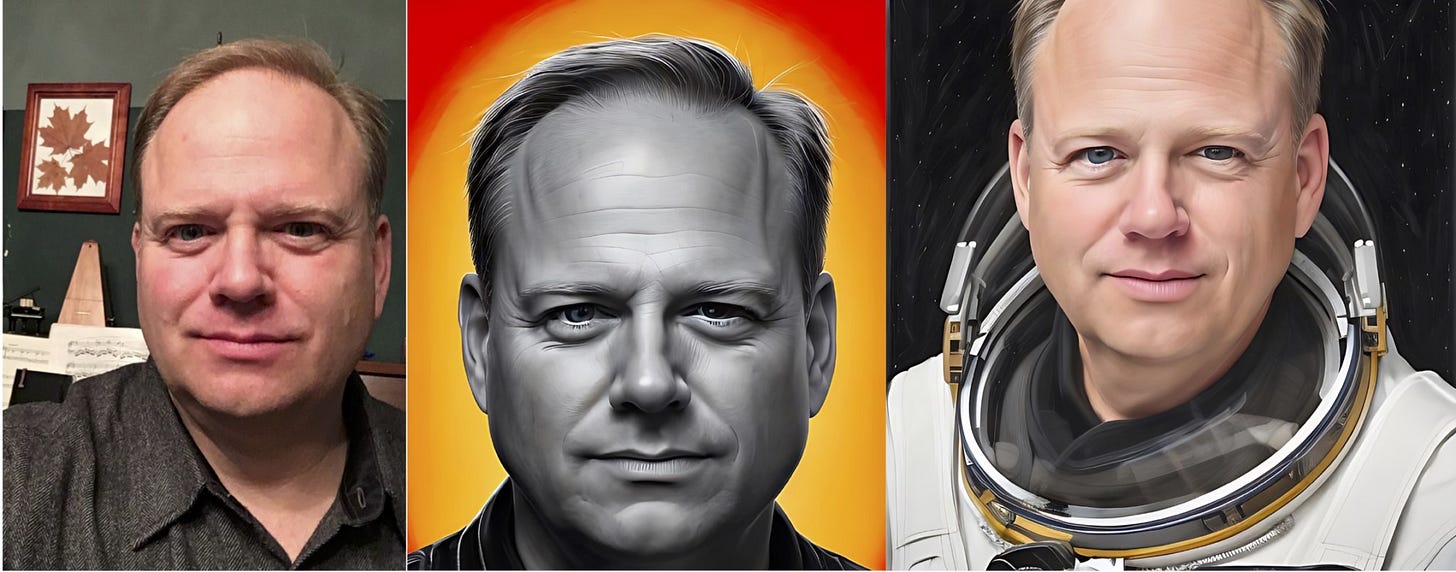

This follows the release of DALL-E, which uses written prompts to create AI-generated art, such as “teddy bears working on new AI research on the moon in the 1980s.” Then there is the newest entry, Lensa AI, which uses the selfies on your phone to generate a series of images of you in different styles, some equivalent to what you might get if you asked an artist or illustrator to draw you. Here I am in real life, versus two Lensa re-creations:

This sort of thing tends to capture the headlines because it provides reporters and commentators with splashy images we can share and lets us fantasize about being astronauts. But the more important uses of AI are those that don’t get the big headlines. Consider Copilot, software developed in part by OpenAI, the same organization behind ChatGPT, but for writing software code. Given a prompt to write code to achieve a particular function, Copilot will churn out a workable result. Here is an overview from TechCrunch:

Available as a downloadable extension, Copilot is powered by an AI model called Codex that’s trained on billions of lines of public code to suggest additional lines of code and functions given the context of existing code. Copilot can also surface [i.e., suggest] an approach or solution in response to a description of what a developer wants to accomplish (e.g., “Say hello world”), drawing on its knowledge base and current context. . . .

With Copilot, developers can cycle through suggestions for Python, JavaScript, TypeScript, Ruby, Go and dozens of other programming languages and accept, reject or manually edit them. Copilot adapts to the edits developers make, matching particular coding styles to autofill boilerplate or repetitive code patterns and recommend unit tests that match implementation code. According to one estimate, with this AI assistance, a programmer can complete a task in half the time it would otherwise take. Then there is a recently announced $6 billion deal in which a major pharmaceutical company bought the rights to a molecule (the basis for a drug to treat autoimmune disorders) that was discovered using AI. If we’re looking for AI applications that are about “atoms not bits,” then here it is, and it is just the beginning.

A Work Sandwich

The new AI is still highly limited in what it can and cannot do. DALL-E and Lensa still have notable problems with hands, often rendering their subjects with six fingers. Inigo Montoya, beware. ChatGPT, when asked a question about the political philosophy of Thomas Hobbes, produced a result that is “a confident answer, complete with supporting evidence and a citation to Hobbes work, and it is completely wrong.” Those of us whose jobs involve knowing the difference between Hobbes and Locke are not going to be out of work any time soon. Many ChatGPT responses have the distinctive air of an inattentive student trying to bluff his way through an answer on a topic he has only skimmed.

The best way to understand the current state of AI is to understand the Trough of Disillusionment artificial intelligence has been floundering in since the first great wave of enthusiasm about self-driving cars. About eight to ten years ago, self-driving technology made a few leaps forward, and there was a great deal of confidence that we would have self-driving cars hitting the market as early as 2018. Elon Musk kept promising “full self-driving” by the end of the year, year after year. It still hasn’t happened.

But the self-driving car was always going to be the hardest application for AI to tackle because it is one in which the machine has to be right nearly 100% of the time. Given our tendency to make allowances for human error but not for machine error, the AI behind a self-driving car has to be not only as good as a human, but much better.

The most productive areas for AI, for the near future, are going to be those where AI can mess up a lot of the time and still be useful. Take the Lensa AI images shown above. The program used about 15 pictures of me—I am not the selfie-taking type, so I really had to scrounge for them—to generate 100 images. I would only ever consider using perhaps a half-dozen of them. Some don’t look much like me at all; the AI got the mouth or the eyes or the forehead completely wrong. Some look a lot like me, but they look almost identical to the photos I already have. Only a few added something that I thought was interesting and potentially usable. But if it takes only a few minutes and a few dollars to generate them, then only a few more minutes to sift through them and pick out the good ones, it just might be worth it.

Yet notice that this requires human work and effort on both ends. It requires humans to start things off by creating the right prompts—to decide what we want and how to tell that to the computer—and it requires humans to finish the job by sorting through the results and improving or refining them.

The usual analogy is that of a work sandwich: human thought and effort at the beginning and the end, with automatically generated AI results as the sandwich filling in the middle. This still requires a lot of human knowledge and judgment. The human operator has to know enough to decide what tasks are worth doing and to evaluate the results.

In contrast to the hopes of the visionaries and the fears of the techno-pessimists, AI will augment human work instead of replacing it.

The Automation of Automation

You could argue that this is what artificial intelligence has been doing all along, and early forms of AI have become so embedded in our normal workflow that we don’t even notice them.

The science fiction version that we’ve come to think of as AI is a fully human-like intelligence, even a superior super-intelligence. But the actual definition of artificial intelligence is any machine built to do what would otherwise have required human intelligence. By this definition, a pocket calculator is AI. It adds and subtracts, just like a person! So are spell check and autocomplete, or the calendar on your phone that pings you with a reminder that you have a conference call in 15 minutes. We have been living with simpler versions of AI for decades—from autocorrect to an airplane’s autopilot—and we already rely on AI to speed up rote and routine tasks.

So what’s new this time? Why is this new AI different?

Copilot is probably the best example. Existing AI automates relatively simple and formulaic tasks. The new AI will automate or semi-automate tasks that are more complex, less formulaic and more creative, such as writing computer code or answering questions in a chat.

Automation of production is nothing new. It has been central to the economy since the Industrial Revolution. What the new generation of AI makes possible is the automation of automation. Up to now, when we want to automate something, that means designing a machine that will perform that task, and only that one task. If we want to make something or do something different, a human has to come in to redesign the machine or reprogram it.

But we’re on the cusp of technology that will allow us simply to decide what new thing we want to do, and as with Copilot, the AI will figure out how to do it. This is why there’s so much excitement surrounding the new AI technology: It has the potential for a great leap forward in human productivity. If a programmer can write code twice as fast, how much more work will everyone else be able to do with AI?

This is exactly the sort of thing we need right now. There has been a lot of talk recently about a “Great Stagnation,” the idea that productivity increases have slowed down in recent decades. The most intriguing speculation is that big productivity advances require a new “general-purpose technology” that comes along very infrequently, something like the assembly line or electrification. A general-purpose technology isn’t just a breakthrough in one field but one that applies across all fields and increases the productivity of everyone and everything.

If we are looking for such a technology that will jump-start productivity—and perhaps help pull liberal societies out of their current funk—artificial intelligence is the most promising candidate, and these new innovations bring us closer to AI having that big practical impact.