The Press Now Depends on Readers for Revenue and That’s a Big Problem for Journalism

By Andrey Mir

Who should fund newspapers and magazines, advertisers or readers? Most people, of course, would say readers. Many media critics and news consumers have long argued that corporations influence the press through their advertising, and this leads to distorted news coverage that favors corporate agendas. They believed that if instead of advertisers, the press depended on readers for revenue, this distortion would end. The press would now report only objective truth because this is exactly what people want and are willing to pay for.

Well, the critics have gotten their wish. Over the past decade, a tectonic but largely unnoticed shift has happened: After 20 years of shrinking ad sales, much of the print and online news media now depend more on readers than on advertisers. At major legacy publications such as The New York Times, subscriber revenue far outstrips advertising revenue.

But this certainly hasn’t led to a new golden age of journalism, with readers getting the unvarnished truth and public discourse being conducted by well-informed officials and citizens armed with facts. It turns out that the primary demand of many subscribers isn’t objective truth. They want publications that support their beliefs and confirm their biases. If a publication doesn’t do that, they threaten to cancel their subscriptions.

Companies were not inclined to cancel their advertising because they needed the large audiences that mass-circulation publications supplied and they weren’t so concerned with what the stories said. Readers have more leverage—if their news outlet eases up on former President Trump or says some nice things about Democrats, they can switch in seconds online to a publication more to their liking. More importantly, if a publication starts gaining a reputation for stories that don’t align with the ideological expectations of its potential audience, sales of new subscriptions will falter. So now it’s readers, not advertisers, whose displeasure the media fear the most.

Probably no publications were better at giving readers exactly what they wanted than the Times and The Washington Post during the Trump years. Setting themselves up in opposition to Trump, both more than tripled their digital subscriptions as progressive readers signed up in droves. The Times boasted 7.8 million subscribers at the end of the first quarter this year.

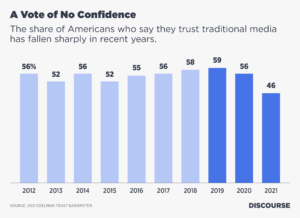

However, slanting news coverage to attract more subscribers discredits publications in the eyes of many nonsubscribers. The dissatisfaction that people have with the news media and the accusations of lies and biases now seem greater than ever. Blame that partly on Trump’s endless attacks on the media, but nevertheless, trust in traditional media outlets has declined to an all-time low.

U.S. print newspaper and magazine advertising peaked in 2000. Soon the internet began vacuuming up that revenue. In 2000, classified ads generated $19.6 billion, a third of the newspaper industry’s ad revenue. Then along came Craigslist, eBay and other online shopping sites, which offered a better service for a lower price or for free. By 2019 classified ad revenue had plummeted to only $2.3 billion.

Competition for display ads was also intense as small and big ad budgets started migrating to the internet. At Forbes magazine, print ads reached 6,083 pages in 2000. They fell 39% the next year and 73% by 2013, the last year the Association of Magazine Media publicly released figures. Publications sold digital ads but couldn’t charge anywhere near what they had charged for print ads. As the saying went, print advertising dollars were replaced by digital dimes and then by mobile pennies, as smartphones became the dominant method for accessing the internet.

Google and Facebook delivered the next blow. The advertising model at legacy outlets was “carpet bombing”—a publication gathered as many readers as it could in a demographic group or geographic area and then sold that readership to advertisers. Every reader saw the same ads whether they were in the targeted group or not. Now, the algorithms of the tech giants know the personal preferences of each internet user and can customize ad messages to everyone individually and at any scale. Digital ads on the legacy media’s online sites simply can’t compete with the relevancy, scalability and efficiency of this form of ad delivery.

In the 20th century, advertising revenue made up roughly 75% of the budget for most daily newspapers. Companies charged only a nominal price for subscriptions, sometimes not covering the cost of delivery, in an effort to build a large audience for advertisers. As advertising fell, however, newspapers started charging higher and higher prices for subscriptions and individual copies, and then began charging for online subscriptions in the late ‘00s. Newspapers started seeing reader revenue as the last hope for staying in business.

In 2014, the model flipped: For the first time, circulation and subscription revenue exceeded advertising revenue at newspapers worldwide. That came just after the U.S. newspaper industry reached a milestone: In 2013 print ad revenue adjusted for inflation fell below its level in 1950, the year the industry started measuring ad revenue and when the U.S. population was less than half its current size.

But this reversal didn’t mean that reader revenue was replacing ad money. It was just that aside from the tiny number of national newspapers and magazines where subscriptions were booming, reader revenue was struggling to stay flat while advertising was falling fast and winning the demise race.

With readers now holding most of the cards, the nature of journalism changed. Its dependence on advertising had determined much of how it was conducted. But the more that news organizations depended on reader revenue, the more they needed to cater—some critics say pander—to readers. “The basic assumption of the news business model—the subsidy that advertisers have long provided to news content—is gone,” said Larry Kilman, secretary-general of the World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers, in 2015. “This is a seismic shift from a strong business-to-business emphasis—publishers to advertisers—to a growing business-to-consumer emphasis, publishers to audiences.”

In the golden age of old journalism—the last decades of the 20th century—newspapers and magazines held a strong grip over the ad budgets of many companies. As a result, ad revenue was plentiful and that allowed publications to keep advertisers at arm’s length and protect, more or less, the autonomy of the newsroom.

Ad money affected publications mostly in how it was allocated to the ones that appealed to affluent readers with money to spend on what was being sold, promoted a consumer lifestyle and avoided certain controversial topics that might hurt brands and reduce readership. Media critics called this system “allocative control,” and it meant that publications with the richest readers maintained newsrooms that enjoyed the biggest budgets.

But in day-to-day operations, the newsroom was largely insulated from individual advertisers wanting to kill a story or trying to plant a story. Ethical codes and professional standards—such as objectivity, fairness and balance in covering both sides of a conflict—kept advertisers at bay and also helped keep the quality of coverage at a high level. Newsrooms aimed to avoid the appearance of conflicts of interest by not allowing their journalists to become involved with business or partisan interests. This “operational control” not only gave journalists a moral high ground but also made the most professional outlets more influential and their ad business more profitable.

The Washington Post newsroom in 2016. Image credit: Mandel Ngan/AFP via Getty Images

The long dependence of the news media on advertisers during the last century gave journalists time to build those elaborate protective mechanisms. Media theorists such as Walter Lippmann and Noam Chomsky analyzed the impact of advertising on journalism and outlined the consequences to newsrooms and society.

Then, as ad money abandoned the print media at the beginning of this century, journalists were suddenly left face-to-face with readers, with no time to adjust. As readers began calling the shots in ways that advertisers never did, these standards—especially objectivity and the restrictions on conflicts of interest—have fallen out of favor. In some quarters they’re even sharply criticized, accused of not being in step with an era that some critics believe demands an ideological news agenda.

This sea change has moved journalism from “manufacturing consent” in society, as Chomsky and Edward Herman noted in their 1988 book, to often dividing society because the best way to boost subscriber rolls and produce clicks is to target the extremes on either end of the spectrum.

The media industry still hasn’t fully reflected on how the rapid switch from ad revenue to reader revenue dramatically changed journalism. And not only has this seismic shift in the business model coincided with a sharp decline in the business, but it’s also gone unnoticed by many people inside the industry and critics on the outside.

Publications might be able to regroup and adjust their standards to a time when their audience, rather than advertisers, is the leading source of revenue. But the challenge is holding that audience. Newspapers and magazines relied on reader money once before, in the 19th century, but the audience today is much different. People suffer from subscription fatigue; they’re weary of being constantly solicited by subscription services of all kinds.

So, not only has ad money fled, but many readers are also reluctant to pay for news, especially since they’re bombarded with free content. Regional newspapers that were formerly local powerhouses struggle to sign up online subscribers. As of last year, the Los Angeles Times had only 257,000 subscribers, the Boston Globe 223,000 and the Chicago Tribune 125,000—numbers that are hundreds of thousands of subscribers below their peak print circulations.

What’s more, with their posts and newsfeeds on social media, readers have acquired their own power to assess the news and set the agenda, something unimaginable 25 years ago. In fact, the power of the audience on social media now exceeds the power of the news media itself. In the past, advertisers held allocative control over newsrooms, but newsrooms, largely protected by professional standards, exercised operational control.

Now newsrooms enjoy neither allocative nor operational control, thanks to the relentless pressure from readers. Headlines and stories are changed and editors are forced to resign after readers flood their social media channels with complaints. Paradoxically, journalists have helped develop this power because they often agree with the complaints and are among the most active users on social media.

The audience is the last large potential source of revenue for newspapers and magazines, but they are by no means the last or even an essential source of news and information for the audience. In other words, they need the audience but the audience doesn’t need them nearly as much. This asymmetry not only erodes the quality of journalism but represents an existential threat to the business.

In 2015, just when the situation seemed desperate, the major national newspapers, magazines and news websites did get a short reprieve. Donald Trump came along and gave the media something to sell that turned out to be in demand. On the supply side, the media were ready to eagerly give the audience whatever it still might want. On the demand side, Trump activated the demographic groups that wanted news outlets to fight for their worldviews, both on the right and the left.

Thus, everything was in place for a perfect storm in the media in time for Trump’s presidency. For the major national publications, the ideological zeal that seized the media during Trump’s tenure temporarily solved their business concerns, but for some it came at a cost: an accelerating decline in decades-old journalistic standards and a further drop in credibility with the public. Now, with Trump gone, many media leaders still habitually look for ideological solutions, and sadly, this might be their only option.

There may be no non-ideological solutions left to save the press because the last residual demand for its content is for ideologically slanted coverage. Some readers are willing to pay to support a “cause,” but not so much for traditional news coverage. This puts the press at the mercy of the last consumer—the most vocal and politicized part of its old audience. Journalism has mutated into post-journalism.