The Lost World of the Liberty Movement

Tim Sandefur’s “Freedom’s Furies” brings back to life the forgotten political culture that gave birth to the 20th-century liberty movement

The past, as they say, is a foreign country. They do things differently there. That’s part of the point of traveling, whether to distant lands or to the past: to understand how things might be done differently, and better, and to ask if the arrangements we take for granted might not be necessary after all.

We tend to regard the current alignments of our ideological coalitions as eternal and unchanging. On top of those alignments, we also accept a set of cultural associations that become attached to our partisan loyalties—assumptions about what kind of person adopts certain political views: urban or rural, religious or secular, rich or poor, white collar or blue collar. But these associations are more ephemeral than we think, and not so long ago, many of them were very different.

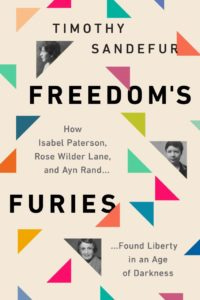

Tim Sandefur’s new book, “Freedom’s Furies: How Isabel Paterson, Rose Wilder Lane, and Ayn Rand Found Liberty in an Age of Darkness,” offers us a valuable and engaging travelogue through one of these foreign countries, showing us the origins of the 20th-century liberty movement in the persons of its three “furies”: Isabel Paterson, Rose Wilder Lane and Ayn Rand. In sketching out their lives and ideas, he introduces us to a cultural milieu so different from today’s that it has been almost entirely forgotten.

The Village Rebels

Ayn Rand is probably the most famous of the three “furies” today, a philosopher and novelist known as a champion of individualism and capitalism. She also achieved the greatest commercial success, with the publication of her runaway bestseller “The Fountainhead” in 1943. But that same year, in a remarkable confluence, the two other women also published fierce defenses of liberty. Isabel Paterson, an influential New York literary columnist and Rand’s mentor, published “The God of the Machine,” an examination of the principles behind the American political and economic system. Rose Wilder Lane published “The Discovery of Freedom,” which was not a commercial success—though Lane turned out to have a much larger cultural influence through her rewriting of her mother’s memoirs of growing up on the frontier, which were published as the enduringly popular “Little House on the Prairie” series.

Ayn Rand, champion of individualsim and capitalism. Image Credit: "Talbot"/Wikimedia Commons

These writers may be considered “conservative” in the sense that they were attempting to defend the individualism and self-reliance of America’s founding and the capitalist system that sprang from those values. But these values are mostly regarded as conservative today because of the superficial political associations created by later attempts to fuse the philosophies of rugged individualism and free enterprise with the religious traditionalism of the conservative movement spearheaded in the 1950s by William F. Buckley and National Review.

In the 1920s and ’30s, however, things were quite different. In the most illuminating section of Sandefur’s book, examining the part of this history that was newest to me, he describes the influence on all three women of a literary movement known as the “Revolt from the Village.” The starting point for these women was reading, not the works of Austrian economists or even the Federalist Papers, but rather the novels of Sinclair Lewis. His 1920 novel “Main Street” chronicles how a small town’s anti-intellectualism and conformity—a complex he dubs the “village virus”—slowly extinguishes the soul of an idealistic young woman.

Today, we would think of this aversion to the narrow-mindedness of small-town life as a marker for left-wing views, but it was a theme that these defenders of individualism embraced. Both Lane and Paterson were from small towns on what had once been on the frontier, and they escaped as soon as they could, in Lane’s case heading all the way to Albania and then spending much of her life as a wandering reporter. In “The Fountainhead,” Ayn Rand would famously dissect conformism and its obsession with respectability.

Sandefur writes:

They saw themselves as genuinely modern, and they viewed fascism, communism, and the New Deal as reactionary movements that sought to turn back the clock, undoing the progress toward individualism they had experienced in their youths and reimposing the authoritarianism and philistinism so well pilloried in Main Street.

Sandefur offers good summaries of the three women’s ideas and explores the differences between them. Paterson and especially Lane embraced a vague form of religion, in distinction to Rand’s atheism, and over time they became more sympathetic to the traditions they had rebelled against in their youth. But none of them was ever really a traditionalist, and they lived what can only be regarded as highly unconventional lives.

Coastal Elites

Sandefur notes that “women in the early 20th Century had experienced an unprecedented liberation.” The three subjects of Sandefur’s book were part of what Paterson called the “Airplane Generation,” a cohort of women who escaped their farms and small towns, traveled the world and went to the big cities to pursue careers. Surrounding them in this book are many other such women. Paterson’s editor was Irita Van Doren, and Lane and Paterson were friends with Dorothy Thompson, an influential reporter and radio commentator who was the inspiration for Katharine Hepburn’s character in “Woman of the Year.”

Lane and Paterson were both in their thirties when women were given the right to vote. They were conscious of the fact that theirs was the first generation to escape the drudgery of farm labor, and to have a genuine opportunity to define their own lives and participate in American democracy and the American economy. Their opportunities were still far from truly equal, but it was a bracing new freedom nonetheless. . . . As women, they knew all too well how freedom can be destroyed by those who claim they are only trying to “help,” or who try to “protect” people from the obligations and rewards of living their own lives. They viewed the New Deal as precisely that kind of debilitating paternalism.

Isabel Paterson, literary columnist. Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

What is perhaps more remarkable from today’s perspective is that these women came up through the world of art and literature. Similarly, H.L. Mencken and Henry Hazlitt—the latter was a leading free-marketer of the time and a friend of the trio; he and Mencken would be fused into the crusading pro-liberty columnist Austen Heller in “The Fountainhead”—were both editors of the American Mercury. This was one of the prominent right-wing publications of the early 20th century but also one of its leading literary journals. Paterson was a key figure covering the book publishing scene in New York City, while Ayn Rand started out as a scriptwriter in Hollywood and later hobnobbed with studio executives and movie stars.

These people were what you might call “coastal elites”—yet they argued for laissez-faire economics, promoted individualism and fought against the left.

Subversive as All Hell

By contrast, the “progressives” and big-government types of the era were often on the side of the village. They were advocates of conformism and enforcers of it.

Rose Wilder Lane, "subversive as all hell." Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

One of the most welcome developments in the past few years is that just about everyone has finally come to realize what a terrible person Woodrow Wilson was. In his day, Wilson was the great hero of the progressive movement, and he sought to expand the power of government and establish a vast administrative state. At the same time, he championed segregation, censored and imprisoned dissenters and instituted domestic spying. But Wilson was hardly alone, and the main focus of Sandefur’s book is to retrieve from its historical memory hole the growing authoritarianism of Franklin Roosevelt’s policies during the 1930s.

Sandefur recounts one example in particular. In 1943, Rose Wilder Lane wrote a postcard to her local radio station responding to one of its broadcasts with criticism of the Social Security program.

When the local postmaster saw Lane’s postcard, he contacted the FBI. It dispatched a pair of state police officers to her home to interview her. Indignant, Lane demanded to know what right they had to investigate her political opinions. . . .

“Was writing the postcard a “subversive activity?” she asked. The cop muttered yes, to which she replied, “Then I’m subversive as all hell!” . . . As with many of Lane’s stories, it probably became embellished in the retelling, but when journalists asked the FBI, it admitted the incident happened. In fact, Lane’s complaint became a personal embarrassment to FBI director J. Edgar Hoover when the American Civil Liberties Union’s executive director Roger Baldwin, an acquaintance of Lane, wrote to him directly to ask about it. This may have been the act of one overzealous local official, but it reflected a wider trend of the New Deal era in which the vastly expanded powers of government were used to boost FDR’s supporters and punish his critics.

One of the pleasures of “Freedom’s Furies” is finding characters from “Atlas Shrugged” popping up in real life. Hugh Johnson, the former general tasked to be a kind of economic dictator under the National Industrial Recovery Act, who was famous for being drunk and abusive, clearly helped inspire Ayn Rand’s brutish commissar Cuffy Meigs. General Electric president Gerard Swope, who proposed a plan to “stabilize” the economy with Mussolini-style industrial cartels, is recognizable as a model for the progressive businessman Jim Taggart. “Atlas Shrugged,” Sandefur argues, was Ayn Rand’s novel of the New Deal, and the programs of the New Deal were a playground for the unscrupulous and power-hungry.

This history offers some interesting lessons that put today’s political realignments in context. “Freedom’s Furies” reminds us that respect for individualism and free markets was once the creed of leading artistic and literary figures in the big city—while there is a natural alliance between big government and small-minded authoritarianism.

This may be a lost world in some respects, but it is also ominously familiar at a time when both left and right have turned against individual rights and are competing to offer their own versions of the village virus.