The Lies We Tell Ourselves To Keep Going

In Virginia Feito’s novel, “Mrs. March,” a privileged Manhattan housewife faces the inevitable consequences of self-deception

By James Broughel

A criticism sometimes leveled at laws enacted in Washington is that they achieve the opposite, or at least something completely different, than the stated name of the statute. For example, the “Affordable Care Act,” while reducing health insurance premiums for some, also made premiums more expensive for a wide variety of individuals who already had insurance. The Patriot Act, with its provisions for government surveillance, is viewed by many as anything but patriotic. And the Defense of Marriage Act denied countless individuals the option of marrying.

Adding to the list of Orwellian legislative names is the recently signed Inflation Reduction Act, which a wide range of experts agree will not affect inflation substantially. Given the existence of such misleading titles, a reasonable question to ask is if they are just a perverse rhetorical tool—intended to pull a fast one over on an unsuspecting American public. Maybe. But what if, instead, the sponsors of these laws actually believe their own hype? What if they are pulling a fast one on themselves?

Chronicler of self-deception. Franz Kafka in 1923. Image Credit: Klaus Wagenbach Archiv, Berlin

It is this tendency to deceive ourselves that has long fascinated artists, authors and social scientists. A famous example comes from the work of Franz Kafka. His short novel “The Metamorphosis” is nominally about Gregor Samsa, a salesman who awakens one morning to find he has turned into a giant bug, often depicted as a cockroach. On the surface, it’s a clever, funny, fantastical story. But it also has a more sinister message, which is that families keep secrets they often have trouble facing privately, let alone publicly. In this sense, the story is a frightening allegory about the lies ordinary families tell themselves to keep going.

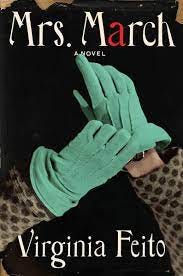

A more recent example comes from the 2021 book “Mrs. March” by Spanish author Virginia Feito. It’s about an Upper East Side housewife who is married to a successful novelist, George. Mrs. March is a part of the upper echelon of elite, New York City society. But she is also a neurotic and unlikeable woman, plagued by an obsession about what other people think of her.

Early on in the book, we are inclined to think Mrs. March is the byproduct of a rotten culture that encourages people to compete in perverse, zero-sum status competitions. And indeed, this is the case. But we gradually learn there is something more disturbing going on beneath the surface. Specifically, Mrs. March becomes convinced one of the characters in her husband’s books, an unattractive prostitute named Johanna, is inspired by her.

Mrs. March also starts to suspect her husband has murdered a young woman who disappeared in a small Maine town where he goes on hunting trips. Mrs. March suffers delusions in the form of optical hallucinations and also delusions of grandeur, imagining herself a sleuth solving a murder mystery and bringing her husband to justice.

Themes of identity show up again and again in this smart, captivating book. At one point Mrs. March takes on the identity of a New York Times reporter in order to investigate her husband’s supposed crimes. She is disgusted by her own naked image in the mirror, and constantly makes awkward attempts to avoid seeing her unclothed self before bathing or while dressing. We don’t even learn Mrs. March’s first name until the book’s final lines, making her a kind of nobody and “every-woman” all at the same time.

Mrs. March experiences a personal transformation over the course of the book, suggesting that she—like Gregor Samsa—may be undergoing a metamorphosis. One is reminded of the movie “Persona,” by Ingmar Bergman, which is nominally a story about two women, one who takes care of the other as a nurse, but is really about two sides of the same woman’s personality—one presented to the outside world and the other kept secret and tucked away inside. At one point near the end of the book, Mrs. March finds herself lost among the reflections cast by her bedroom’s many mirrors. The reader is left wondering: Which one is the real Mrs. March?

One of the more pleasurable and entertaining aspects of this book is catching on to its many allusions to other works of mystery and horror. Mrs. March’s first name, Agatha, is likely a reference to Agatha Christie. Indeed, the name “Mrs. March” is so similar to “Miss Marple,” one of Christie’s two great detective creations, it could hardly be a coincidence. Mrs. March visits a small town in Maine where the characters possess thick Maine accents, reminding the reader of characters from Stephen King’s novels. A dead pigeon in a bathtub—a hallucination of Mrs. March’s—might be an allusion to Alfred Hitchcock’s movie “The Birds.” Meanwhile, cockroaches show up periodically in the apartment, again reminding one of Kafka.

Queen of Crime. Agatha Christie in 1958. Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Other creepy moments abound in this clever little book, including an anxiety-raising visit to a psychic, where Mrs. March receives a foreboding Tarot card reading. Perhaps Mrs. March’s name is also a reference to the astrological sign Pisces or to the spring equinox, which occurs in March, as these esoteric symbols have a close connection to the Tarot.

“Mrs. March” is in part a sly commentary about the superficiality of the super-wealthy on New York’s Upper East Side. It’s also a commentary on the role of housewives in society and the empty struggle involved with keeping up appearances. Yet, if all that was wrong with Mrs. March was that she buys into a culture that is phony and superficial, that would make for a pretty boring book. What makes this story such a page turner is Mrs. March’s dark side. Like Gregor’s family in “The Metamorphosis,” she has a dirty little secret she holds onto and can’t even admit to herself.

To one extent or another, we all tell lies to ourselves to help avoid confronting reality. Politics has a funny way of reflecting this troubling characteristic of our personalities, which is one reason for the Orwellian titles of so many laws. The problem is that self-deception is not innocuous. It is like a rot that festers over time, eventually metamorphosizing into something highly destructive. At that point, the only way out is to face reality head on.