The Future of Taiwan: Living Through the Decades of Sparring With China

By Joyce Huang

When I was growing up in the 1970s, we were educated to be Chinese in Taiwan by the ruling Chinese Nationalist Party, or the Kuomintang, which retreated to Taiwan in 1949 after its defeat by the Chinese Communist Party in China.

School textbooks said the KMT would lead us to “eventually retake China” and “liberate” millions of mainlanders across the Taiwan Strait, who were so poor under the thumb of the “evil Commies” that they had nothing but tree roots to eat. It wasn’t until much later we realized that Communist propagandists also painted people on Taiwan in a negative light, saying that we lived under thatched roofs and had nothing but banana peels to eat.

The Taiwan-China hostility runs deep in both societies and cuts across people of all stripes, although the majority of Taiwan natives, like me, used to find that kind of animosity irrelevant. That’s because my family had neither been truly at war with the Chinese nor separated from any mainland relatives. But it was a period of authoritarian rule in Taiwan, and parents taught us to just hush up about politics.

At home, the KMT’s party-state regime posed a bigger threat to many dissidents than the distant enemy of China. Dissidents would be put behind bars or even on death row if they were found to be critical of the authorities, sympathetic to the Communists or advocating for Taiwan’s independence. I once read in old newspaper clips that local intellectuals who called for democracy, freedom and the rule of law in Taiwan surprisingly won praise and endorsement from the CCP. That suggested not only the old KMT-CCP rivalry, but also the democratic façade that the CCP put on in the early days and its attempts to win over the hearts and minds of people in Taiwan.

Abroad, the world began to engage with China following the U.N.’s unseating of Taiwan in 1971 and China’s opening-up policy launched in 1978. One by one, countries, including the U.S., severed diplomatic ties with Taiwan and shifted their official recognition to the CCP as the sole legal government of China.

'One China With Different Interpretations'

Growing international isolation in the 1980s turned Taiwan into the “Orphan of Asia” politically. But our government continued to insist that Taiwan was part of the KMT’s China, or the Republic of China, not the CCP’s China, or the People’s Republic of China, and that the CCP was our common enemy and source of hatred. Indeed, the KMT was right about this because the CCP later deployed hundreds of missiles aimed at Taiwan and has never renounced the use of force against Taiwan. Before the deployment in the 2000s, the two parties agreed to disagree under the 1992 consensus: “one China with different interpretations,” a political dodge that was flatly rejected by the island’s emerging grassroots forces advocating for Taiwan’s sovereignty.

The ever-growing Taiwan-China divide gave birth to the ideas of two Chinas and “one China, one Taiwan.” That second idea morphed into an independence-leaning movement, and nowadays the island’s mainstream identity is to see ourselves as Taiwanese instead of Chinese. Independence-minded or not, most people here prefer Taiwan being called a country simply because it is a fait accompli: We have our own elected government, military and currency, among other elements of a modern country.

But, this has caused me some trouble for years because I mostly report for international news outlets, which, with no exception, revise my referral of Taiwan as a country to an island. It frustrates me since there’s nothing I can do to change the world’s incorrect perception of Taiwan.

Putting political complications aside, Taiwan was doing very well economically in the 1980s and joined South Korea, Singapore and Hong Kong to become “the Asian economic miracle” and one of “Asia’s four little dragons.” American technology companies set up assembly lines here and helped train local talent. Gradually, Taiwan became a high-tech powerhouse, with products made in Taiwan sold to countries around the world that have no diplomatic ties with us.

Economic freedom then enabled us to seek greater political participation and usher in Taiwan’s democratization. With the U.S. acting as its security guarantor, our small island was at once both economically and militarily stronger than its giant neighbor China. (A military expert told me that before the 1980s, it was Taiwan that frequently sent warplanes to fly over China’s Fujian province as a show of force.) As a result, Taiwan is probably one of the most U.S.-friendly places in Asia, and it now fully embraces American-style democracy.

Taiwan’s policy of no contact with China officially ended in 1987 when locals were allowed to visit their mainland relatives. Those who set foot again in their former hometowns and then returned to Taiwan shared proud stories of how their red-envelope money and “three major appliances as gifts”—television sets, refrigerators or washing machines—had been well-received among their belt-tightening mainlander relatives.

Moving to China

Taiwanese businesses began to move their factories to China, taking advantage of cheaper land and labor, even though the Taiwanese government urged them to make no haste. Quickly, products made in China replaced those made in Taiwan. What came next was the story of China’s rapid rise, with many debating whether China posed a threat or an opportunity.

I traveled to China for the first time in 2001, to report in Fujian province on feedback on Taiwan’s implementation of “three mini-links” to the mainland. The Democratic Progressive Party government had launched boat rides between Taiwan’s offshore islands of Kinmen and Matsu to China’s cities of Xiamen and Fuzhou with the aim of bringing people across the Strait closer. I did feel a sense of familiarity there since I spoke both Mandarin and the local dialect of Hokkien. But there was also this invisible wall that I sensed and that undeniably differentiated me as a Taiwanese and the mainlanders as Chinese.

As someone who already enjoyed rights to freely elect township chiefs, lawmakers and the head of state, I found the Chinese political mentality and its one-party state backward. But I saw no reason why Taiwan couldn’t normalize relations with China. And like many, I was convinced that the Chinese would one day catch up economically and politically and, when that day came, Taiwan could serve as a role model of a market-based economy and the only Chinese democracy.

China did catch up and its economic might and military power have surpassed Taiwan’s. Restrictions for mainlanders to visit Taiwan were relaxed in 2008 under the pro-Beijing leadership of Taiwan’s ex-president Ma Ying-jeou. And millions of Chinese tourists have arrived and traveled across Taiwan. I remember my relatives and friends in the service sector all extending a wholehearted welcome to the Chinese spenders even though some of those from Beijing criticized Taiwan’s international airport as being outdated. But few admitted that they were particularly fond of the Chinese for a reason I can only guess, that the Chinese Communist leadership remains a political bully toward Taiwan.

Still, to many businesspeople in Taiwan, China was more of an opportunity than a threat, until recently. As its military might grows, China, under its increasingly assertive leader Xi Jinping, is making more and more threatening noises. Over the past few months it has frequently sent military jets to fly over Taiwan and conducted military exercises that are said to be preparation for invading Taiwan.

But, as many analysts here have predicted, this psychological warfare of China’s has failed to intimidate the people of Taiwan because, after decades, we are used to China’s coercive messages. And few are surprised by the neighboring superpower’s hostility toward the independence-leaning Democratic Progressive Party government, although, to some, it appears to have spiraled out of control amid best-ever U.S.-Taiwan ties and worst-ever U.S.-China relations.

The New Generation

What’s different from the past is Taiwan’s “born independent” millennials. They’re not afraid to speak up against China, especially after its oppressive and Cultural Revolution-style attacks on young freedom fighters in Hong Kong over the past year. No doubt the island’s increasing anti-China sentiment can only further fuel tensions across the Taiwan Strait, although Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen is considered to be more prudent than her predecessor, Chen Shui-bian.

As a journalist, I’ve never heard louder warnings about how the Strait can easily become the top flash point between the U.S. and China, which could lead to an actual confrontation. Equally loud are worries and doubts over the resolve of the U.S. administration, whether under ex-President Donald Trump or current President Joe Biden, to come to the island’s aid if China makes the first move to invade Taiwan. Many ask: Are the American people prepared to go beyond statements and sanctions to fight the Taiwanese’s war? Or even if they are, will the American soldiers arrive in time to help expel the Chinese military, whose capabilities may hold the advantage over its U.S. counterparts in several critical areas? No one has a definitive answer.

To avoid a potential conflict, strategists in Washington such as Council on Foreign Relations President Richard Haass and research fellow David Sacks called on the U.S. government last September to introduce a policy of “strategic clarity” to make it explicit that “the U.S. would respond to China’s use of force against Taiwan.” They argued that “waiting for China to make a move on Taiwan before deciding whether to intervene is a recipe for disaster.” Those who disagree say the proposed policy shift would not substantially enhance deterrence but instead would be provocative.

They noted that the U.S.’s longtime posture of “strategic ambiguity” over Taiwan has managed to keep China at bay for four long decades and will continue to do so. While the debate goes on, Japan and the U.S. recently issued a joint statement underscoring “the importance of peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait”—an apparent move to counter China’s growing assertiveness.

I share many strategists’ viewpoints and concerns, but I also understand why Taiwanese are complacent. An old man once told me confidently that “the Commies dare not attack because the U.S. military is backing us like our big old brother,” and many in Taiwan agree. He used the phrase “big old brother” in a positive way, unlike in George Orwell’s 1984.

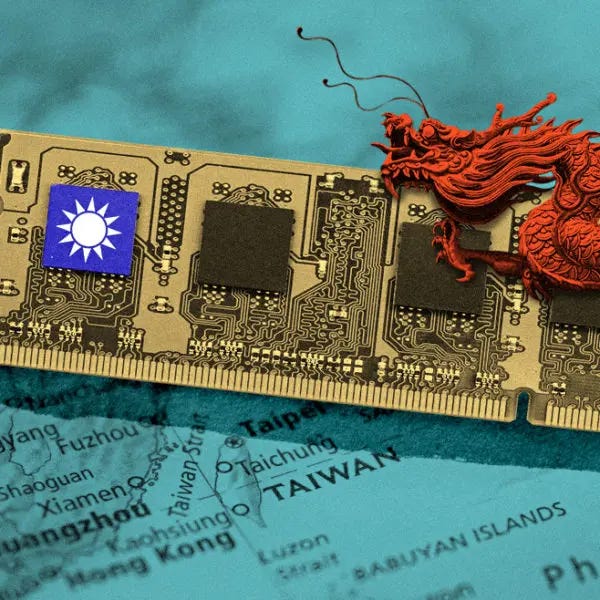

I agree with him, but I have my own reasons. One of the main ones is that Taiwan’s semiconductor sector is so strong that it’s in America’s interest to protect it to maintain U.S. tech supremacy over China, which is at the heart of the two superpowers’ long-standing competition. As many analysts have pointed out, that competitive edge will work like a “silicon shield” to protect Taiwan against China.

But China could also use the excuse of defending Taiwan’s tech strength to trigger its aggression and accelerate its timetable for retaking Taiwan. Scholar Niall Ferguson has likened Beijing to a “diplomatic hedgehog,” which he said knows one big thing and “that big thing may be that he who rules Taiwan rules the world.” Taiwan’s strategic importance is indeed rising. But certainly I hope that China isn’t ready to make that risky and aggressive move.

This is the fourth and final article in a series on “The Future of Taiwan.” The first article focuses on steps the U.S. can take at home and abroad to prevent a Chinese invasion of Taiwan. The second article discusses the obstacles facing a Chinese military conquest of Taiwan. The third article highlights the importance of Taiwan's semiconductor industry.