The Fifth Wave: Is the Medium Really the Message?

Ezra Klein, Marshall McLuhan and the question of structure over content

In a recent New York Times opinion piece, Ezra Klein shares a guilty secret: “I didn’t want it to be true, but the medium really is the message.” As a millennial, and thus part of the first generation of digital natives, Klein tells us that he “adored” the new medium with its “endless expanses of information.” He adds: “My life, my career and my identity were digital constructs as much as they were physical ones.”

Of course, we all know where this is headed. Trump and Twitter happened. This “felt like a sinister apotheosis,” also known as a Very Bad Thing. Inevitably, Klein fell out of love with the web. To his credit, and unlike most anti-technology crotchets, he looks for an explanation for this failed romance among media theorists who have a lot to say on the subject.

First up is Nicholas Carr, who wrote “The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains.” Now, I confess I haven’t read Carr; I couldn’t get past the title. According to Klein, Carr describes the web as a form of addiction, a “hunger.” We leave always craving more. There’s certainly truth to that, as anyone can attest who has lost hours of life in the pursuit of online memes. TikTok has become the fastest-growing social media platform by giving the user more: the mandatory brevity of the videos makes TikTok feel like a feast of stuff. The same is true of Twitter and the 280-character limit. Conversely, Facebook’s complicated format makes it an inefficient pusher of digital addiction.

Compulsive behavior is never good. Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff have warned that, among teenagers, particularly girls, web addiction can be destructive in many ways. For adults, however, it’s mainly a waste of time—which, at worst, is an antidote to the Puritan work ethic. Klein recalls a dramatic moment of recognition: “Hunger. That was the word that hooked me. That’s how my brain felt to me, too. Hungry. Needy. Itchy.” But having confessed that his life, career and identity were digital constructs, and that he felt not only okay with this but superior to “those who came before me,” the itch to reenter the construct shouldn’t come as a surprise.

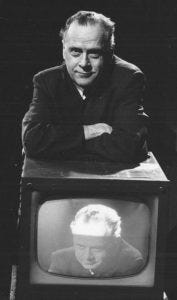

Next up is Marshall McLuhan, famous today, as Klein reminds us, for his oracular judgment, “The medium is the message.” “For the ‘message’ of any medium or technology,” he further explained, “is the change of scale or pace or pattern that it introduces into human affairs.” McLuhan was among the first to grasp that the structure of information is far more determinative than the content.

This is not an intuitive concept. “We’ve been told—and taught—that mediums are neutral and content is king,” Klein notes. Consequently, all our information fights are over content. Whole countries can be punished by the big platforms if the content is unacceptable: Recently, Denmark announced it had banned Covid-19 vaccinations for people under 18 and got red-flagged by Twitter for its troubles. The reason, in part, is that we are blind to structure—we don’t think about letters when we read—but mostly because our informational tussles are conducted as if nothing has changed since the 20th century.

Think of it this way: The structure of information sets the stage and arranges the props of the human drama. The digital medium, for example, looks like the studio of a Marx Brothers movie. Violent slapstick comes naturally there. Pomposity gets mocked without mercy. Of course, important people—our elites—hate this structure. Since pomposity is their reason for living, they wish to cram a different content into the web: Rather than “A Night at the Opera,” say, they expect Shakespearean dignity—they demand “Hamlet.” Yet the structure imposes the terms of the performance. Even if “Hamlet” is mandated from on high, it will be Groucho sneering through “to be or not to be,” and the soliloquy will be punctuated with pratfalls.

Content has a short half-life. It’s the medium that applies a constant pressure on politics. Klein, who is a liberal and a Democrat, seems to believe that Republican presidents can only get themselves elected through some form of media malfunction. Reagan was an actor who knew how to smile at the TV cameras. Trump was a reality TV star and a master of the explosive tweet. In truth, however, any successful politician must learn to perform in the dominant medium of the age. Franklin Roosevelt, though a Democrat, understood how to use his radio voice to tremendous effect. Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign brilliantly exploited the internet to defeat two stodgy establishment figures, Hillary Clinton and John McCain.

Politicians whose skills are misaligned with the medium are condemned to failure. Richard Nixon was eviscerated by television. As for Joe Biden, let’s just say that his attempts at communication are a thin thread of content immediately appropriated by the digital and repurposed into memes.

Though McLuhan was a brilliant wielder of the epigram, some of his deeper dives tend to baffle even the sympathetic reader. There is an urge to simplify. If the medium is the message, then that message must be a single powerful effect. “Television turned everything into entertainment and social media taught us to think with the crowd,” Klein writes.

I’m not sure we gain much by simplifying media, whose effects, demonstrably, are layered and complex. Television is less about entertainment than about incoherence and visual promiscuity. After all, you can be sobbing over a character’s death in a televised drama one minute and then suddenly plunged into a commercial selling diapers for incontinence the next. You can flip between Laurence Olivier’s “Hamlet” and the hapless Washington Nationals. Such proximity poses a riddle. Television, according to McLuhan, is a “cool” medium: We fill in the blanks. Each TV viewer constructs an “Alice in Wonderland” world of imagery liberated from causality, in which the cosmic and the absurd, “Hamlet” and incontinence diapers, sequentially coexist.

Even the pace of TV programming has a social impact, as McLuhan suggested. The old television-by-appointment model trained us to patience and forced us to watch together, while streaming encourages binging and solitude.

As for social media, Klein is absolutely correct that it aims to convert users into a vast conformist herd—but that has come at the end of a process that began in the opposite direction. The early internet brought about a great fracturing of the public. Or, more accurately, it allowed a fractured public to be itself, as the gravitational pull to remain a “mass audience” suddenly vanished. Two decades ago, the public shattered like Humpty Dumpty and has never been put back together again. This means that both conformity and disintegration are at work in the digital medium today: That’s how you get ferociously loyal online war-bands skirmishing over every aspect of reality, from Covid vaccines to the shape of the earth.

Another effect of the digital medium is more indirect but may also be more profound. The moment one enters the online environment, the self begins to liquify. The lack of external or internal pressures makes it impossible to maintain a definite shape or character. On the web, you can be anyone or anything—a vertigo-inducing condition that is equivalent to being nothing. Identity, which in traditional culture was pressed hard upon us by social forces and in modernity became problematic, now dissipates into thin air. Those of us who are of a certain age will borrow attributes from the analog world. But the young make no distinction between virtual and real. They are stuck on a question that is part narcissism and part fear of the monster in the labyrinth: What am I?

Let’s be clear: This is a pathological affliction. It’s the cause of much anxiety, depression, even suicide. The youngest generation boasts of its fluidity: You can be any one of 72 genders, alter your online portrait to fit some ideal of perfection and, if the mood strikes, you can become someone else entirely, again and again. What is affirmed isn’t freedom but necessity. What is experienced isn’t discovery but confusion. The herd instinct in the young runs far deeper than the algorithms of social media. By being told which words are mandated and which are taboo, which opinions are safe and which are “harmful,” an artificial membrane is produced to hold, in a facsimile of identity, the liquid self.

It may be that the lure of populism depends to some extent on this effect. Populists like Trump and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez are skilled actors who can project outsized, sharply defined personalities across the digital medium. Their supposed “authenticity” is really a performance—an ability to play-act boldness of character—that could be perceived as guiding stars in the darkness by those suffering the process of identity dissolution.

Klein concludes on an optimistic note. That may seem unwarranted but it accords perfectly with the rigid conventions of New York Times opinion pieces, which always follow the same pattern: bad news + getting worse + catastrophe = reason to hope. Citing Jenny Odell’s “How To Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy,” Klein suddenly discovers choice, agency and “the revolutionary potential of taking back our attention.” He insists that this isn’t a plea to unplug and turn our backs on technology, and maybe he’s right—but other than the conventional happy ending, I’m not sure what, exactly, the argument is.

If we are in the grip of a vampirical hunger, an irresistible addiction to online buzz, then saying “let’s take back our attention” begs the question of how. I think that question points directly at the future. We’re not returning to the days of ink-stained editors and paper boys thudding a wad of newsprint on our front doors. Short of retrograde despotism, the digital medium can’t be caged, conquered or silenced. What then? To paraphrase Andrey Mir, who is the McLuhan of our century: Since we can’t kill or “fix” the digital medium, we’ll have to find a way to live with it.