The Era of Nepo Babies Is Upon Us

Wealth and privilege have their advantages, but they will only get you so far

By James Broughel

In a 1962 televised debate, a 30-year-old Teddy Kennedy was vying to fill a U.S. Senate seat left vacant by his older brother John when he became president. Teddy’s opponent was the more established Massachusetts attorney general, Edward McCormack. At one point during the debate, McCormack pointed a finger disapprovingly at Kennedy, publicly questioning whether he was qualified to be a senator when he was just three years out of law school.

McCormack declared boldly before the audience, “If his name was Edward Moore with his qualifications ... your candidacy would be a joke. But nobody's laughing.”

Moore was Kennedy’s middle name, but the attempt to call out Kennedy for not checking his privilege famously backfired. Voters came to see the attack as mean-spirited and unfair, and perhaps more importantly, an indirect attack on a popular sitting president. Young Teddy swept into office, and went on to be elected to eight full terms as a U.S. senator.

Growing up in Massachusetts, in a Democratic household where the Kennedys were elevated to near-sainthood, this story was relayed to me many times during my childhood. It is useful because it highlights the double-edged sword of nepotism. On the one hand, it is undoubtedly true that without the Kennedy name young Teddy’s candidacy really would have been a joke. But it’s also true that voters liked Teddy’s association with his more famous older brother. Plus, over time Teddy proved himself a capable dealmaker in the U.S. Senate, in some ways transcending—or at least making good use of—the Kennedy name to become an effective representative for his state.

Today, the term “nepo baby” has become popular to describe people who benefit from their ultraprivileged backgrounds. Miley Cyrus is one such example, whose father Billy Ray had a huge hit in the early 1990s with the silly, but super-catchy country song, “Achy Breaky Heart.”

It’s easy to poke fun at the twerking Miley, but we shouldn’t be too hard on the nepo babies. After all, anyone who has good genes, whether their parents are famous or not, is privileged to some extent. The children of athletes have a leg up when it comes to making the major leagues. The same is true in academia. One recent study found that tenure track faculty at universities were between 12 and 25 times more likely than the general population to have a parent with a Ph.D. That means a lot of smart people are nepo babies too.

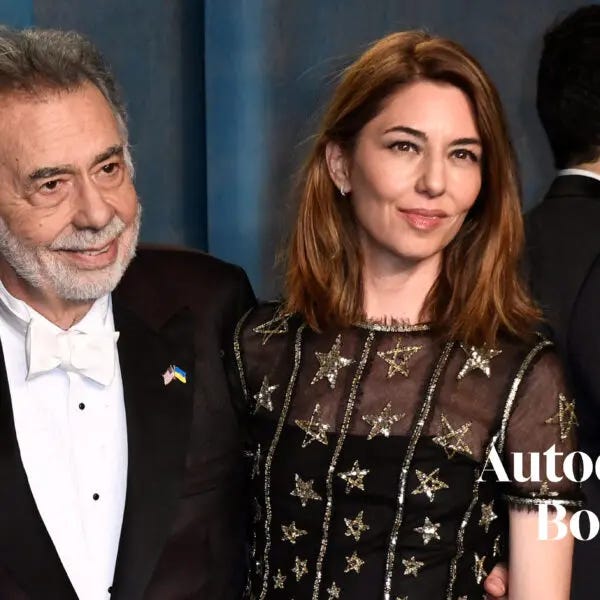

Talent is talent, and it should be respected and recognized regardless of where it comes from. Sure, “Lost in Translation” was directed by Sophia Coppola, the daughter of the famous film director Francis Ford Coppola, but it’s also a great movie in its own right, irrespective of Sophia’s upbringing. When one considers that other Coppolas include actors Nicholas Cage (Francis’ nephew, he changed his name to avoid the association), Francis’ sister, Talia Shire, and her son, Jason Schwartzman, one does have to wonder if a lot of talent stems from good genetics.

Of course, these individuals may never have gotten a chance at the spotlight without their family connections, but there’s also survivorship bias going on here. Thousands of people are children of or are otherwise somehow closely associated with famous people. Many of them are trying to make a go in show business, and almost none of them succeed. So to claim that privilege is all that’s going on with the Mileys and Sophias of the world fails to recognize the unique aptitudes these individuals possess in their own right.

One of the things I learned living in New York City for over a decade is just how chock-full of semifamous people the city is, and how easy it is to form connections to many of them. I had one friend who dated Johnny Knoxville, the star of the hit MTV show “Jackass” (she herself was the daughter of super-rich parents and lived in one of the Trump towers). The singer in the band I played in dated (and had his heart broken by) Regina Spektor, who went on to become a famous singer. I had several friends who played in bands with Sean Lennon.

I mention these people not to name drop, but to showcase that in a city like New York, a relatively regular guy like me found himself surrounded at times by some pretty well-known people. Most of the time, these associations weren’t nearly as helpful for advancing a career as one might think.

“The Great Gatsby” wrestles with some of these themes of old versus new money and insider versus outsider status. In the book, the world of elite New York and Long Island is portrayed as morally and spiritually vacuous, and indeed, nearly a century later, this is something I witnessed living in New York City too. The music scene, in which I spent a lot of time, included a lot of independently wealthy young people. And like some of the characters in “Gatsby,” many of them just seemed lost.

In F. Scott Fitzgerald's masterpiece, "The Great Gatsby," many characters live spiritually empty lives. Image Credit: Francis Cugat/Wikimedia Commons

The singer in a friend of mine’s band was one of the heirs to the Guinness beer fortune. He was a super nice guy and, much like Jay Gatsby, the parties he hosted at his huge loft apartment on Avenue A overlooking Tompkins Square Park were legendary. But sometimes I wondered if people like him were in bands because they loved music, or because they loved to party, had money to spend and needed a way to pass the time.

“The Picture of Dorian Gray” by Oscar Wilde is a story that captures the ugliness that sometimes lurks inside those who on the surface appear to have everything. This helps explains why so many of the most privileged people in our society fall victim to drug or alcohol abuse. On the other hand, the rich are people too. Many of Jane Austen’s novels, such as “Emma,” playfully illuminate the petty romantic squabbles of the rich, but they also show us that the rich are basically just looking for the same thing as everyone else: They want to love and be loved. Even Jay Gatsby, who was willing to do nearly anything to achieve wealth and status, ultimately only wanted the love of his lost sweetheart, Daisy.

In New York, I never envied those people who were born into the upper echelons of wealth and privilege. It seemed to me like more of a curse than a blessing. For every Anderson Cooper who made a name for himself—he’s the son of heiress, Gloria Vanderbilt—there are a hundred Hunter Bidens. Many of them don’t survive to tell their tale.

Ironically, Edward McCormack—the would-be senator who sparred with Teddy Kennedy during that Massachusetts debate—was himself no stranger to nepotism. He was the nephew of John McCormack, a one-time speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives. The example just goes to show that many of us are not that far removed from privilege. In fact, a single adult today making $50,000 a year is richer than almost 99% of the world’s population. We should remember that the next time we call out someone for being born with a silver spoon in their mouth.

Being a nepo baby has its advantages to be sure, but privilege will also only get you so far. And even if one “succeeds” by conventional standards, the “victory” can often feel pyrrhic in the sense that the expectation is always to achieve more money and more fame.

Unfortunately, one aspect of human nature is that there seems to be no amount of material wealth that makes us satisfied. Moreover, achieving status is often even more important to us, and that’s a zero-sum game—for every winner there must be a loser. Whether we can ever get off this wheel and appreciate how good we have it is an open question. Here too, for better or worse, we can learn a lot from the nepo babies.