The Economic Nationalists’ Banana Republic

Nationalist conservatives’ embrace of “industrial policy” points to a Republican Party much friendlier to big government—and much more willing to accept cronyism as a way of doing business

The attempts of Donald Trump-supporting “MAGA Republicans” to overturn the last election have been the focus of the recent hearings that laid out the nature and planning of the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol. While the threat to free elections is and ought to be our main focus, there is another important lesson to be learned from these events. In showing us what the scramble for power always tends to look like, they remind us what form government action takes when a faction’s pious slogans and big promises meet their implementation.

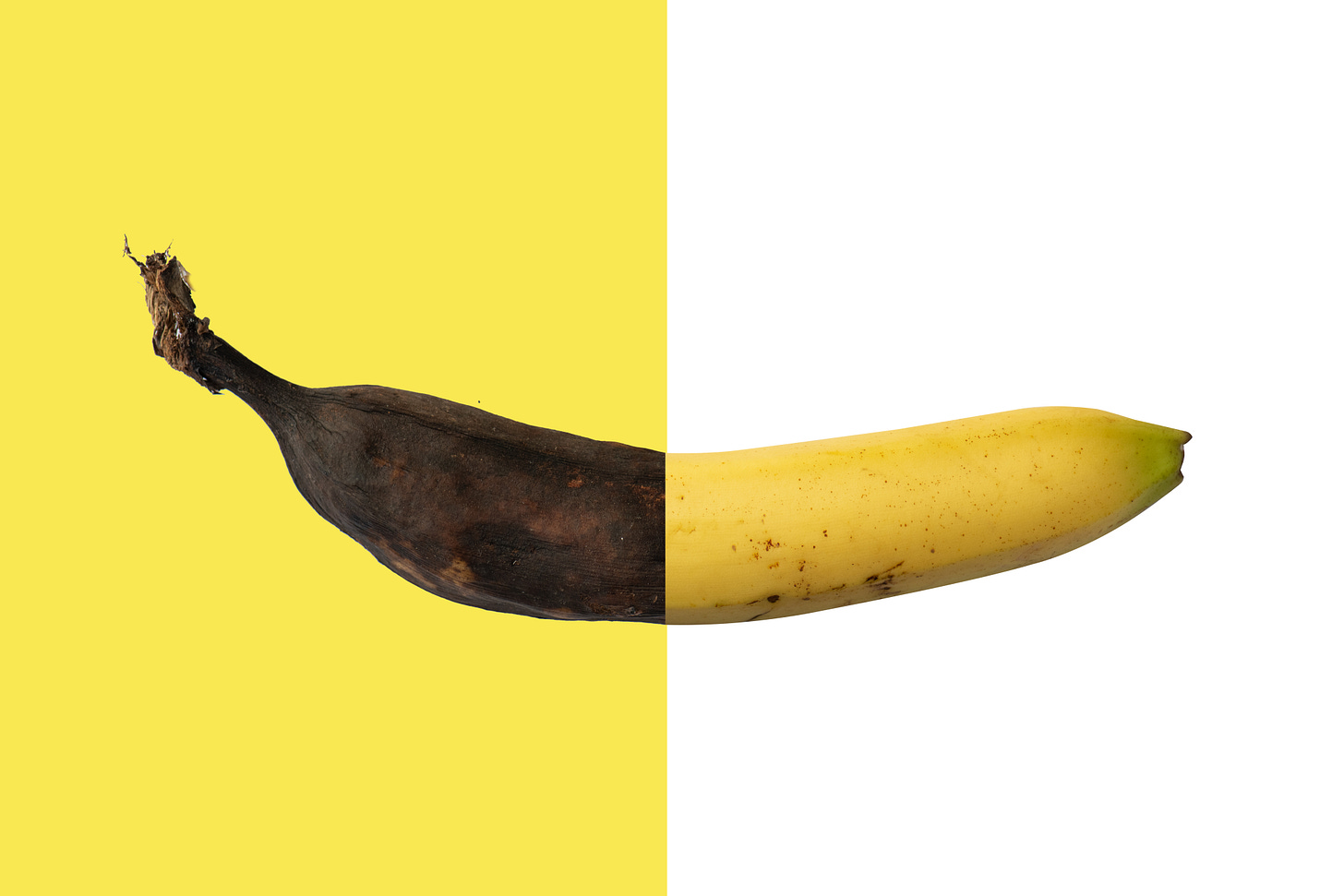

If Trump and his chaotic band of supporters seem like the Keystone Cops staging a coup in a “banana republic,” that has a lot of implications for what big government—particularly of the nationalist variety favored by Trump’s wing—would actually look like if they return to power.

Central Planning by Any Other Name

The new breed of nationalist conservatives who are influential on the MAGA Right regard free marketers and old-style libertarians as anathema, arguing that they diverted the Republican Party to the cause of tax cuts while letting “globalism” destroy industrial jobs and (allegedly) undermine the traditional family—a traditional family viewed through a haze of false nostalgia.

Instead, they have embraced the cause of industrial policy, a euphemism for central planning. Oren Cass founded a whole think tank devoted to the idea that politicians are better at allocating capital than the market. Missouri Sen. Josh Hawley proposed a bill giving Commerce Department bureaucrats the power to determine which products have sufficient domestic manufacturing content. Florida Sen. Marco Rubio has gone from campaigning as a successor to Ronald Reagan to warning about “the perils of free-market fundamentalism” and advocating a “21st century pro-American industrial policy.”

In theory, all of this would be managed by wise planners immersed in the data and dedicated to serving the national interest and saving the American family. In practice, it would be run by the same crew who ran the Trump administration and now runs the former president’s PR machine in exile.

The Rogues’ Gallery

The Jan. 6 insurrection, Trump’s continued agitation about a supposedly stolen election, and his latest scandal over mishandling of classified documents provide vignettes that remind us who would actually be in charge and how that individual would be acting.

One of the more colorful characters in this rogues’ gallery is Mike Lindell, the ex-drug-addict turned entrepreneur who became a Trump favorite and has gone on to host a YouTube network and plan underwhelming rallies where he spouts conspiracy theories about the 2020 election. In all of Lindell’s harangues, the blockbuster evidence that will break everything wide open is always just about to be revealed. His role in the insurrection? Visiting the White House to promote a plan to impose martial law.

Then there is crackpot lawyer Sidney Powell, who promised to “unleash the Kraken”—a reference to a mythical sea monster from a cheesy movie—by which she meant a series of lawsuits making extraordinary claims about the election. But those claims faded away when subject to the evidentiary standards of a courtroom. The Kraken never came, but it all made a good talking point to whip up Trump’s base.

Then there is the gang that organized the unintentionally comical election press conference at the Four Seasons in Philadelphia, which turned out not to be a luxury hotel but instead the parking lot of a light industrial building that houses Four Seasons Total Landscaping. To this day, no one seems to know why.

Or take Donald Trump’s recent trouble with retaining classified documents at his personal home in Florida. Apparently, part of the reason the FBI seized the documents is that one of Trump’s closest advisers, Kash Patel, has been going around on talk radio vowing to release sensitive information. Patel is a guy on the make who has gained Trump’s ear and risen rapidly out of obscurity. He now sells hats emblazoned with his name, stylized as “K$H Patel”—as if to boast that this is all a grift and everyone knows it.

Peter Navarro, perhaps the biggest booster of industrial policy in Trump’s Cabinet, was one of the architects of the president’s restrictive trade policies. He has long been committed to protectionist policies, writing in 1993 that “the essence of a national industrial policy is a full partnership between government and business.… [T]he role of government is to help a nation’s businesses compete by providing technological assistance, subsidies and protectionist measures such as tariffs and quotas.” It was Navarro who also devised the wild-eyed Green Bay Sweep scheme in which the Senate would hold an all-night session, declare the 2020 election results invalid, and have the presidency decided by a Republican majority in the House of Representatives.

These are just a few examples of who would have a say in industrial policy and deciding what enterprises are in the national interest. Obviously, they would choose the ones favored by opportunists and yes-men, including their own various cons.

All the Way Down

Now, you could say that this clown car is just who is running the show on the political and PR end of Trump’s organization and is not representative of what a nationalist conservative administration’s actual policy would be on substantive issues. But the evidence indicates otherwise.

Consider the last-minute pardons Trump issued for a raft of his cronies, a serious presidential power that says a lot about how he prefers to use his authority. Recipients included Elliott Broidy, a top campaign fundraiser who was later convicted for “a covert campaign to influence the Trump administration on behalf of Chinese and Malaysian interests” and former campaign strategist Steve Bannon, who was being prosecuted for fleecing Trump’s own supporters by raising money supposedly to build a border wall. These pardons were a signal that Trump intends to protect open, flagrant corruption.

Or consider one of the crowning examples claimed by Trump early in his presidency as a triumph for his power as a dealmaker-in-chief in bringing manufacturing back to the United States. In 2017, Trump loudly announced a deal with the Chinese firm Foxconn to build a $10 billion LCD factory in Wisconsin that he proclaimed would be the “Eighth Wonder of the World.”

The whole deal fizzled out, and last year the facility was largely abandoned. It is likely the whole project was never intended to go forward; Foxconn officials never explained what was actually happening at the plant or what its economic rationale was, producing instead a comical stream of vague promises and evasions. But the whole thing had a definite political rationale: to curry favor with the leader who was then in power.

The Trump administration’s scandals are reminiscent of the inner workings of a banana republic, and the president’s exercise of industrial policy largely followed the model of a banana republic.

The Industrial Renaissance of Cold Fusion

This is not merely a partisan failing; it is not just about nationalists or populists or Republicans.

I remember the last time there was a big push to revive central planning—excuse me, industrial policy. That was back in the 1990s, during the early years of Bill Clinton’s presidency, and the man pushing this idea was the Clinton administration’s chief policy guru Ira Magaziner. But just a few years earlier, Magaziner had testified before Congress pushing for millions in funding for cold fusion, the fanciful notion that a “tabletop” setup could generate enormous amounts of energy from nuclear fusion at room temperature. Magaziner warned, “If we fall behind at the beginning” of this amazing new technology, “we may never catch up.”

But everyone fell behind. The science behind this supposed breakthrough couldn’t be replicated and was widely debunked. The technology never materialized. But Magaziner did OK. He failed upward and was put in charge of drafting the Clinton administration’s plan to overhaul the nation’s entire health care system.

I’m not saying Magaziner was a conscious grifter who knew that cold fusion was bunk. Most likely, he had no way of knowing either way and was just acting on behalf of his lobbying client, the University of Utah. But this just underscores the problem with industrial policy. What you get is not the policy that makes the most sense, even if a central planning committee could reliably determine exactly what that is. What you get instead is whatever pet projects happen to have a friend at court.

Freedom Is Indivisible

The real cautionary tale for industrial policy is the country that is the closest you will get to a banana republic in Europe: Viktor Orban’s authoritarian populism in Hungary. Orban is the MAGA Right’s new hero—he was rapturously received at the Conservative Political Action Conference last month—and his restructuring of Hungarian politics is considered a model for the nationalist right.

Yet a central feature of that system is government intervention in the economy and the symbiotic relationship between economic nationalism and authoritarianism. For example, Orban’s childhood friend Lorinc Meszaros rocketed in a mere five years from being a pipefitter to being a billionaire, thanks to his miraculous ability to get government contracts. The system is set up in such a way that if you want to make money and have a successful enterprise, you have to support the ruling party or else find that the continued existence of your business will be determined not to be in the national interest.

This is the basic chicken-and-egg question of an illiberal society. Does the strongman ruler use corruption to stay in power, or does he pursue power in order to profit from corruption? The most likely answer is … both. Margaret Thatcher used to say that “freedom is indivisible.” Just as economic freedom and political freedom are tied together, so economic nationalism and authoritarian politics are two sides of the same coin.

That’s the implication of the attack on the Capitol for nationalist conservative economic policy. If Jan. 6 looked like an attempted coup in a banana republic, we should remember what else banana republics are notorious for: chaos, corruption and economic backwardness.