The Dark Side of the Screen

Our computers’ journey away from dark to light screens—and back again—shows how digital media influence human behavior

The recent Super Bowl marked the 40th anniversary of the groundbreaking Apple Macintosh commercial that changed not only advertising but the way we use digital devices. Among other things, Apple introduced the light screen to simulate habitual print pages and seduce us into digital usage. Many people by default still use the light mode on the screens of their devices. Some of them don’t even know that there is an option to set up a dark background. To others, the dark mode is an aberration. Why would somebody use the dark mode, so unnatural for reading?

Now, however, more and more users are switching to the dark screen. Why are people offered this choice? How do they choose the dark mode or the light mode? These core questions of digital anthropology can shed light on the tectonic transition from the print era to the digital world.

Nocturnal Creatures

One hypothesis is that the divide between light-screeners and dark-screeners is mostly generational. Older people are digital migrants: We came from the Gutenberg era. The rationale of keeping the light mode on for screens is obvious—this format simulates the appearance of a book page. Many digital migrants would not have even imagined that it could be otherwise. In the print era, a black background with white letters was an artistic technique predominantly employed in posters. It’s close to impossible to read a significant amount of text in such a manner.

Digital natives, in their turn, will likely lean toward a dark screen. There are two primary reasons for this. First, the era of print dominance ended before their time, so black inks on a white page do not hold sway over them. Second, and more importantly, a black screen is genuinely more convenient at night, and night use was the original purpose of the dark screen option. Another name for dark mode is “night mode.” It was assumed that users would switch between the modes according to the lighting conditions.

But I bet nearly nobody does it: The convenience of adapting the screen to different lighting conditions is fairly insignificant amid the annoyance of changing settings twice a day, from black letters on a light backdrop to white letters on a black backdrop and back. So, those who choose the dark mode, whether due to the absence of a book-reading habit or due to their technical proficiency and open-mindedness, will likely stay with this mode around the clock.

The apparent generational divide, however, does not encompass all the nuances behind choosing to use a dark vs. a light screen. The most surprising aspect is that, technologically, if true to its nature, the screen should be dark, not bright. The very emergence of the light screen mode was a global conspiracy of media aimed to seduce humans into the use of a new medium.

The Light in the Darkness

A sign may be defined as a meaningful mark on a meaningless background, a deliberate effort amid inherent nothingness. In terms of energy expenditure, the symbol is “1” while the backdrop behind it is “0.” That is why the screens of computers and other electronic devices were initially dark. If a sign is an active effort on a passive background, then electric marks must be made by firing pixels, gas microtubes, glower filaments or whatever can be illuminated by an electric impulse. Just as it was “natural” for written and printed media to have dark ink on a light page, it is “natural” for an electric screen to be dark with glowing symbols on it.

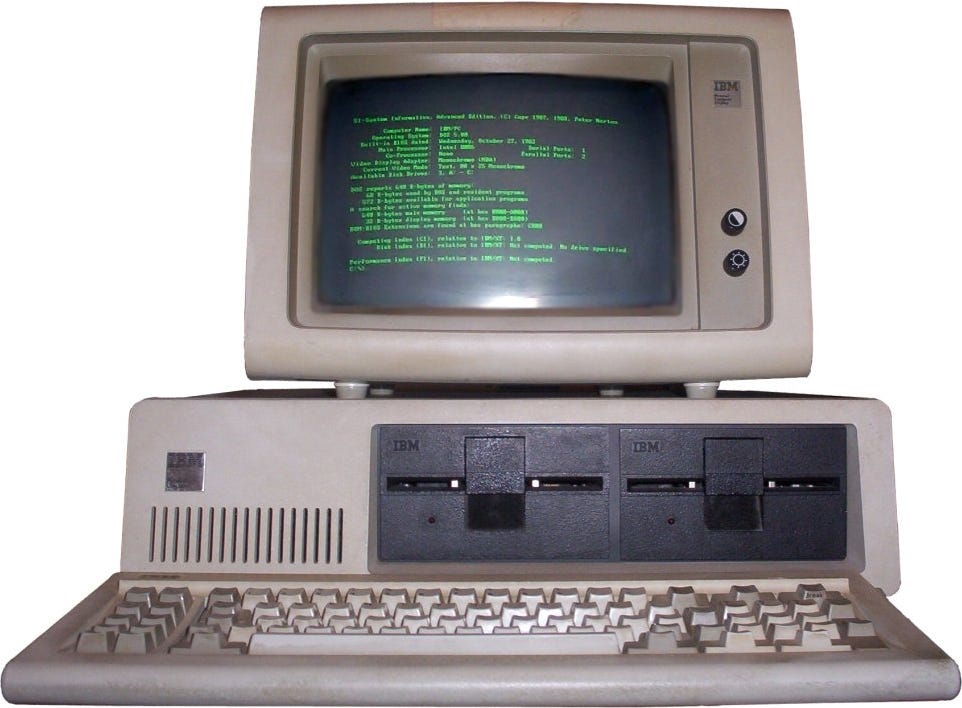

Indeed, the first computers mostly had dark screens. They followed the logic of energy efficiency, not consumer accommodation. Here lies another cultural divide behind the light and dark screen users. Programmers, the creators of the digital world, are more likely to opt for a black background. Ordinary consumers, who use computers for other needs, are more likely to use the light mode. By introducing the light mode, technologically unnatural to screens, computers have accommodated nonprofessional users.

Let There Be Light

We can pinpoint exactly the moment in history when programmers ceased to dominate the population of computer users, and the number of ordinary consumers grew enough to become a new target for computer design, leading to the advent of light screens. This “demographic” shift occurred on Jan. 24, 1984, when Steve Jobs introduced the public to the Macintosh—the first computer specifically geared toward consumers and devoid of the burden of “programmer-centric” heritage in its design.

Apple Macintosh made “the computer for the rest of us.” It had a graphical interface (with pictures) and a mouse, allowing users to interact with any spot on the screen immediately, without running the cursor along the lines and characters. Accommodating regular users led to the emergence of a new principle of computer design: What you see is what you get. The very idea of graphic design made the light background inevitable.

Digital mythology attests that Apple’s team, with Jobs himself, might have gleaned the idea while visiting Xerox. Xerox had been primarily known for its copying technology, introduced for commercial use in the 1950s. However, concerned about competition from the Japanese and fearing that business would become paperless in the future, the company created a computer division, which in 1973 developed the world’s first desktop computer with a graphical interface and a mouse.

Perhaps Xerox’s attachment to paper and office paperwork was an additional factor that prompted the white background of its first graphical interface. In one way or another, the likely involvement of a paper-centered digital corporation in the transition from naturally dark screen interfaces to the paper-like light screen can be considered a kind of Easter egg from the perspective of media evolution. Regardless, the Xerox computer was quite expensive and never took off. Perhaps people at Xerox did not have that Steve Jobs instinct to think of the consumer, not just the product and its functions.

The resemblance of the screen to the printed page with pictures represented a crucial cultural change. The computer industry turned its face to consumers, not programmers. IBM also transitioned from MS-DOS to Microsoft Windows, a consumer-centered interface. And something profound happened: Digital media, born with a dark screen and illuminated symbols, learned to simulate paper to lure billions of people from the paper era into the digital world.

There was no other rationale for the light mode. Computers did not need it. To communicate with programmers, a dark MS-DOS screen with illuminated symbols worked just fine. But a few thousand programmers cannot ensure the development of the digital industry and, consequently, the ongoing progression of digital media. Media evolution needs billions of users who make entrepreneurs invest billions of dollars in the development of new media. This is why media evolution has made computer screens light.

However, a question arises. Yes, light screens seduced the print-trained humans and expanded the demographic of computer users from thousands of programmers to already almost 5 billion consumers. Why, then, is a dark mode back now? Is it just a generational shift, with younger users having less attachment to books with black ink on white pages? Is it because they increasingly use social media at night, in the dark? These factors undoubtedly play a role. But there is something else in the dark screen’s comeback.

Light-On vs. Light-Through

In the 1960s, Marshall McLuhan famously stated that “The medium is the message.” It was (and still is) a hard statement to understand, as communication studies have mostly focused on the transmission of messages, in full accordance with Harold Lasswell’s formula, “Who says what, to whom, through which channel, with what effect?” McLuhan called this method of study the “theories of transportation” and claimed that his approach, by contrast, was the “transformation theory.” He was interested in what media do to people, not what people do with media.

While teaching media at Fordham University, McLuhan’s son, Eric, faced the same issue: The students struggled to comprehend why the medium itself is the message. In 1968, Eric McLuhan and his colleagues conducted the so-called Fordham Experiment, which demonstrated how different media can communicate different messages from the same content. Specifically, the experiment was intended to explore the differences between the perception of TV and the perception of movies.

Students were divided into two groups. In the same room, the same film was projected onto a semi-transparent screen. One group sat on the side illuminated by the projector’s light, and the other sat on the opposite side—the image “shone” on them through the screen. So, the same movie was projected in “light-on” and “light-through” modes. The light-on mode recreated the physical perception—light fell on a surface and shaped images that were perceived by the eye. The light-through mode represented the principle of the electronic screen: Light falls on the eye, passing through the screen with information.

The Fordham Experiment revealed significant differences in audiences’ perception. The main distinction lay in the level of audience engagement. Those watching the movie screen (light-on) perceived what was happening on the screen as alienated events, as objects of observation. They felt more detached from the content and were able to judge the content more rationally and analytically.

Those watching the same film through the screen, with the light directed at them, were more immersed in what was happening on the screen. Reflecting on their viewer experience, they placed greater emphasis on the emotional aspects of perception. They also found it more challenging to correctly evaluate the duration of the film.

In one instance, when the students were watching Buster Keaton’s comedy “The Railrodder” (1965), a participant from the TV group (light-through) even went to the other half of the room to see what the movie group (light-on) was laughing at. It was not that funny on his side, so he wanted to make sure that the other group was being shown the same film. Keaton, nicknamed “The Great Stone Face,” had a peculiar style of comedy without a smile. On the light-through side, involvement placed the viewers in the picture and diminished the comic effect, while the viewers on the light-on side remained detached observers and got all the fun intended by Keaton.

The Fordham Experiment showed that if the light shines on the screen/object, it allows the observer to stay more detached, whereas the light that itself carries information and shines it on you favors better immersion in that information. Visual detachment favors rational, abstract and analytic perception. Visual immersion favors immediate reactions that are likely more emotional and spontaneous.

Screen Instead of Sun

The very principle of light-on belongs to the physical world. Everything is lit up by the sun, and this is how we see things–their shapes reflect sunlight. In the digital world, however, information itself glows, lighted up by electric impulses.

As soon as digital media outgrew the programmer demographics, they began to simulate not electric but physical “illumination” of information to seduce billions of users into digital media consumption. Their “purpose” was to activate market forces for further development of digital media.

But the current comeback of the dark mode indicates that humankind is approaching the final stage of resettling onto the digital. Perceiving information that itself glows is becoming more common than perceiving information that is lit up. Digital media no longer need to simulate physical lighting conditions, so they are reverting to their natural format–the dark mode.

Two centuries ago, electricity began erasing the distinction between day and night, replacing humans’ naturally lit environment with an artificially lit one that is totally controlled by human media activity rather than the “activity” of the sun. Now the information glowing from digital screens is completing this transition from the sun-dependent environment to the screen-dependent environment.

The dark screen, carrying information in light-through mode, no longer unaltered by the simulation of sunlight, not only accommodates media consumption that ignores the “natural” reality of day and night but also enables better and stronger immersion of the users in the reality of the screen. Information glowing onto us users diminishes our ability to perceive objects in a detached way and to control the time spent in media consumption. We invest more time and effort, fully immersing ourselves in digital media. While some decry our screen “addictions” and increased detachment from the physical world, this is precisely what digital media need from us to continue to evolve.