The Dark Side of Historic Preservation

Historic preservation ordinances can limit property owners’ rights, stifle businesses and even hinder the goal of preservation itself

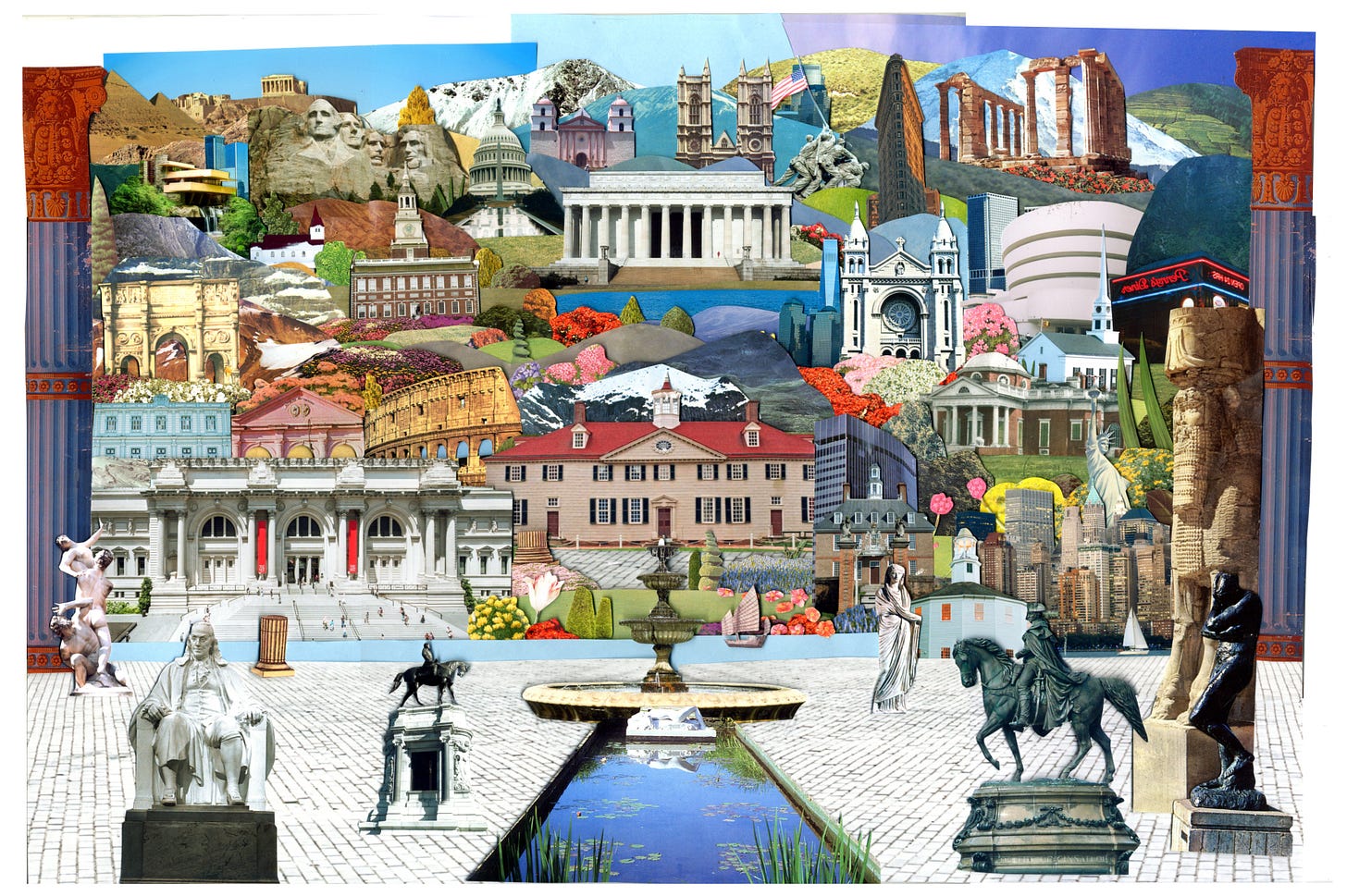

Anyone who has been to Independence Hall, Mount Vernon or Hannibal, Missouri, knows what an enlightening and even moving experience it can be to visit a historic building. The places where history happened can feel like living witnesses to the great events of the past. That makes it natural that we feel an irreparable loss when, say, the home of John Hancock, or a work by the great architect Louis Sullivan, is destroyed.

This hits close to home, if you’ll pardon the pun. I was raised by a family of historic preservationists; my parents were the live-in caretakers at Heritage Square, a Los Angeles museum devoted to protecting old structures. Even after leaving that work, they have devoted themselves to restoring and maintaining 19th century buildings across the country. (They’re currently restoring an old brick mansion in Indiana.) I grew up in a construction zone, surrounded by architectural history and often hearing the slogan, “Old houses need love too.”

But there’s a downside to historic preservation. As Alex Tabarrok puts it, “if today’s rules for historical preservation had been in place in the past, the buildings that some now want to preserve would never have been built at all.” After all, life goes on—and as lovely as old buildings may be, they are not only expensive to maintain and repair, but they can also stand in the way of worthy innovation and necessary development. When the government orders historic preservation by law, the resulting costs are typically imposed on individual property owners in the form of expensive mandates—or on would-be owners, in the form of higher costs for housing.

Government restrictions can also create perverse incentives: A lovely old home can become a costly albatross around an owner’s neck, which scares away potential buyers. And restrictions on construction can deter developers who would otherwise be ready and willing to construct much-needed modern housing.

Good Intentions, Bad Methods

The preservationist cause in the United States is usually traced to the 1860s, when the John Hancock house in Massachusetts was demolished. The resulting outcry spurred efforts to save other revolutionary artifacts and buildings, but interest flagged toward the end of the century. Then, in the 1920s, the cause experienced a resurgence of enthusiasm. Wealthy businessmen such as John D. Rockefeller Jr. and Henry Ford got into the act, with Rockefeller paying to restore Colonial Williamsburg and Ford purchasing dozens of old buildings, such as the Wright Brothers’ bicycle shop, and having them transported to his museum in Michigan.

After World War II, concern for historic structures again waned, until it was reignited by such incidents as the razing of New York’s historic Penn Station, Robert Moses’ scheme to build a highway through lower Manhattan and the demolition of Louis Sullivan’s Chicago Stock Exchange, which cost preservationist Richard Nickel his life.

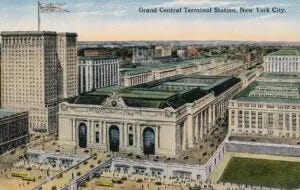

Then, of course, there was Grand Central Station. Built in 1913 by Charles Reed and Allen Stem, Grand Central is a prime specimen of the Beaux Arts style, with a breathtaking star-spangled ceiling where shining constellations seem frozen in orbit around a central golden clock—a perfect encapsulation of bustling Manhattan. By the late 1960s, however, the station was obsolete, and maintaining such a building in America’s most expensive neighborhood was pricey. The newly formed Penn Central Railroad therefore decided not to demolish it, but to build a tall office tower directly over it, in hopes of raising revenue.

New Yorkers rose in indignation—partly because the proposed building was going to be yet another hideous International Style rectangle, but also out of a concern to preserve what was undoubtedly a historically significant building. City officials denied the owners a permit, announcing that the proposed tower would violate the New York Landmarks Preservation Ordinance. Even though the railroad company was not seeking to destroy Grand Central, the city refused to allow it to build in the air above the station.

That presented a legal problem. The Fifth Amendment to the Constitution pledges that the government will not take away private property for public use unless it pays the owner “just compensation,” and the city’s action plainly took Penn Central’s right to use its airspace—dramatically reducing the property’s value. Yet the city did not propose to pay. It said it owed the company nothing because it had not confiscated the land or taken the title but had merely passed a regulation limiting how the company could use the land—no different from countless other regulations the government imposes without triggering the compensation requirement.

In 1978, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the city’s favor, fashioning what has come to be called the “Penn Central test”—a legal theory so biased toward the government that when it’s used, property owners virtually never receive the compensation to which they are entitled. The Penn Central test is an “ad hoc factual inquiry,” the court said, which requires judges to balance “several factors”—meaning that instead of consulting clear and predictable rules, judges award compensation on a case-by-case basis after deciding whether they personally think a restriction on property rights “goes too far.”

In an earlier case, the Supreme Court had explained that the purpose of the “just compensation” requirement is to prevent the government “from forcing some people alone to bear public burdens which, in all fairness and justice, should be borne by the public as a whole.” But the subjective and amorphous Penn Central test, which remains on the books today, lets the government shift the entire cost of maintaining historic property onto individual owners, even if they never asked to be the custodians of a landmark, and even if the property is being preserved solely for the public’s benefit.

Rockefeller and Ford spent their own money to preserve history—but the Penn Central test lets historic preservationists in the government force property owners to do so against their will—and out of their considerably smaller pockets.

‘A Cudgel to Stop Development’

Since then, “historic preservation” ordinances have become commonplace. According to the National Park Service, there are some 2,300 in the United States, and as urban planning expert Adam Millsap notes, these restrictions are often “used as a cudgel to stop development,” rather than to preserve truly priceless buildings. He gives many examples:

In San Francisco, a project to turn a laundromat into an eight-story apartment building was delayed for years in order to determine whether the laundromat had enough historical significance to prevent its demolition. In St. Petersburg, Florida, a couple was blindsided by a third-party historic designation request from their neighbor that delayed a pending sale by six months and cost them $30,000 in legal fees. In Denver, Colorado, preservationists tried to get a 1960s diner labeled a historic landmark to prevent its redevelopment into an eight-story mixed-use apartment/retail building.

What’s more, bureaucrats often deem structures “historic” even though they lack genuine historical value, and the “historic” declaration is merely a manipulative effort to control how people use their own land.

It’s not just restrictions on remodeling or demolishing buildings, either: Politically powerful businesses sometimes use historic preservation laws to stymie potential economic competition. In 2002, the politicians in Islamorada, Florida, adopted an ordinance banning chain drug stores, to protect existing pharmacies from having to compete. Rather than admit to this motive, however, town leaders claimed they were trying to preserve the town’s “historic atmosphere.” Fortunately, a federal court saw through that and declared the ordinance unconstitutional. Islamorada, it noted, “has no Historic District, and there are no historic buildings in the vicinity.”

That decision was a rare exception. Far more common are cases in which preservation ordinances reduce or eliminate property owners’ rights—and courts refuse to enforce the Constitution’s guarantees of just compensation or due process. Take the 2007 case in which a federal court in Kansas denied compensation to the members of a monastery who were forbidden from demolishing a dilapidated structure on their land. Officials rejected their application for a permit, not because the building was historic, but because it was located within 500 feet of buildings deemed historic.

The brothers had spent 16 years trying without success to find a way to fix or use the building before deciding it had to be torn down—but the court, using the Penn Central test, said the government’s refusal had not imposed a severe enough “impact” on their rights to warrant compensation. Cases like these are so typical that the government is, for all intents and purposes, immune from liability if it takes away property rights pursuant to a historic preservation ordinance.

When ‘Historic Preservation’ Backfires

The regulations in officially designated “historic” neighborhoods can be so byzantine and confining—not to mention subjective—that property owners may find it impossible to replace or upgrade even the ordinary fixtures of their homes. Such rules typically subject every choice an owner might make—from lights to windows to paint colors—to review by layers of government bureaucracy. The 57-page book of “Guidelines” for the historic district in Stevens Point, Wisconsin (famous for, well, nothing), is typical: It warns against “replacing transparent windows or doors with tinted or frosted glass,” or removing “character-defining vegetation,” or adding “architectural components and details that are not appropriate to the historic character of the structure.”

Or consider Somerset, Maryland’s instructions to residents of the historic zone who might wish to install an air conditioner: The town “strongly suggests” that residents schedule “a pre-permit meeting” before even filling out the application for a permit, and of course, there’s a fee for such a meeting. Once that’s done, applicants must visit the County Historic Preservation Office for “further instructions.” That office will forward the applicant’s plans to members of the Town Council for their review—and the application must also be approved by the County Permitting Office.

“Once you have both of the county permits,” says the town, “you apply for a Town of Somerset permit and put yourself on the schedule for a Town Council meeting where a decision will be made.” At every stage of the process, there are fees and delays—this in a county where the summers average 85 degrees and 70% humidity.

No wonder some communities have chosen to repeal their historic preservation ordinances. Given the costs, delays and nitpicking that preservation laws can inflict, property owners sometimes resort to demolishing potentially historic properties as quickly as possible, before politicians declare them landmarks. In 2015, the buyer of Ray Bradbury’s Los Angeles home tore it down almost immediately, probably to avoid being saddled with an outmoded house he couldn’t renovate. A Washington, D.C., property owner who swiftly ordered a historic building destroyed in 2002 told reporters she did it because she knew the city would seize the property if she hesitated. More recently, a San Francisco millionaire bulldozed a 1936 Richard Neutra home, even though it had been designated historic. The city ordered him to rebuild it, but backed down in the face of a lawsuit.

Other regulations can also prevent the rescuing of old buildings. Frank Lloyd Wright built a home for his son David in Phoenix in 1952. After David’s wife died in 2008 at the age of 104, it was purchased by investors who hoped to open it to the public. But NIMBY neighbors refused to allow that, so the house had to be sold to private investors who promised to preserve it—but not to let the public see it. Why would anyone undertake the expense and hassle of saving a historic structure, when it’s impossible to recoup one’s investment—or even to offer tours?

In fact, neighbors often use historic designations as a NIMBY tool. Witness the 2017 incident in which Seattle’s historic preservation board blocked a 200-unit building, thereby reducing the availability of more housing and driving up the cost of homes. Officials in Houston are currently trying to use historic designation to block “gentrification” (that is, renovation and improvement) of the Denver Harbor neighborhood. Last year, Philadelphia did the same. Such restrictions aren’t designed to protect the old—but to forbid the new. As historian Jacob Anbinder recently put it in “The Atlantic,” preservation “can function as a pretext for preventing change entirely”—and to further enrich those fortunate enough to already have homes, at the expense of those who would like to.

“All aesthetically meritorious undertakings, including art museums, parks, etc. have some kind of financial cost,” observes Think Progress’ Matthew Yglesias:

If a city or state wants to bear some cost in order to fund a museum, that goes through some kind of appropriation process where the cost is assessed and subject to scrutiny. Historic preservation, by contrast, tends to operate as a kind of ratchet where more and more stuff is added to the list over time and there’s little assessment of the overall impact. Then since nobody actually wants to freeze every structure in place, the key issue becomes which people have the right kind of pull or consultants or lawyers or whatever to navigate the process and get things done.

Even where owners don’t want to demolish buildings, overlapping permit requirements, and the delays accompanying them, can make preservation hard, or even impossible. The congregation of Manhattan’s West-Park Presbyterian Church recently asked the city to repeal the building’s landmark status because nobody can afford the $50 million it would take to restore the building. Preservationists want to see the building remain—but they aren’t shelling out the cash. Yet the city refused, leaving the decaying building to simply sit there. Even when owners try to fix a building, preservation restrictions can be costly. Last year, a New Jersey couple trying to repair their historic home in Montclair suffered a disaster when workers caused damage that rendered the house uninhabitable. Their only choice was to tear it down—but local officials refused to give them a demolition permit.

With such restrictions in place, it’s little wonder that owners of historic buildings sometimes let them fall into disrepair knowing they will ultimately collapse, leaving the owners free to do what they want with their property. It’s a phenomenon so common it’s earned a nickname: “demolition by neglect.” Government efforts to outlaw this practice have proven futile. After all, what’s the government to do? Piling on more financial mandates will only hasten the building’s demise.

A Future for the Past

There are better alternatives. If a community wants to preserve a historic property, it’s only fair to expect the community to pay for it, rather than force owners—who have only one vote each—to shoulder that burden. Thanks to the Penn Central test, owners have little chance of obtaining justice in court. But states can provide greater protections for individual rights than the federal government accords, and some have done just that. The consequences have been more sensible and equitable land-use regulation.

In 2006, Arizona voters adopted Proposition 207, an initiative that, among other things, overrides the Penn Central test and requires the government to compensate owners when it reduces their property value by restricting their rights to use their land. When the initiative was adopted, local government officials howled that it would cost taxpayers immense sums and deprive bureaucrats of power to protect the public. That turned out not to be true. In the ensuing decade and a half, there have been hardly any lawsuits under the initiative. Instead, it has given property owners leverage to resist unjust infringements of their rights, and forced politicians to negotiate fairly about how much historic preservation the public is actually willing to pay for.

Focusing on incentives can also be more effective at preserving old property than stringent rules that increase the cost of repairing or maintaining historic sites. When Tom Messina, owner of Tom’s Diner in Denver, started preparing for retirement, he faced a problem: Locals didn’t want the building—a prominent example of mid-century “Googie” architecture—remodeled or demolished. They circulated a petition to have it declared historic, which would bring with it all the red tape and expense of maintenance, and thereby scuttle Messina’s plans.

Fortunately, a company called GBX Group intervened. If the city would withdraw the threat of regulatory prohibitions, GBX would work to make the property marketable, thanks to various tax credits and preservation grants that made it economically viable to save the building. Denver agreed and relaxed its limits on renovation. The building, adapted in a style that complements the existing architecture while modernizing it, recently reopened as a cocktail lounge. “I didn’t see this coming but it’s really exciting that it worked out the way it did,” Messina said.

Easing restrictions on property use can actually increase people’s willingness to preserve it and eliminating the subjectivity of regulations is essential to ensuring owners’ rights to fairness. Ambiguous rules—such as those that require a renovation to be “compatible with the character of the neighborhood”—can mean anything. Consequently, they often end up meaning whatever politicians say they mean. More than a half-century ago, the U.S. Supreme Court said that any law that requires people to get a permit or a license must specify the criteria for the permit in clear terms, so applicants can know what is or is not allowed. Or, as Justice Felix Frankfurter wrote, “Prohibition through words that fail to convey what is permitted and what is prohibited for want of appropriate objective standards offends Due Process.”

Yet just as courts using the Penn Central test fail to enforce the just compensation rule, so judges frequently shrug at the due process problems when the rules governing historic neighborhoods are written in vague terms. Boise, Idaho’s historic guidelines instruct property owners not to place their solar collectors in a way that “adversely affect[s] the perception of the overall character of the property”—whatever that might mean. Under amorphous standards like that, government power hangs over any property owner’s head like the sword of Damocles, ready to drop without warning.

There’s no reason historic preservation cannot be served by clear and objective rules that tell people what’s allowed and what’s prohibited. The Permit Freedom Act—championed by the Goldwater Institute, where I work, and pending now in several state legislatures—seeks to implement this common sense safeguard.

Preserving the past is a worthy goal. But like all worthy goals, it also represents a tradeoff, with costs and benefits that must be weighed in the balance. Ignoring property rights, the role of incentives and the principles of due process—which forbid vague laws—blinds both politicians and voters to the cost side of the equation. That tends to benefit the politically powerful at the expense of less influential property owners—and of consumers who would benefit from new and more innovative construction. Without legal checks and balances, historic preservation cannot only stifle new building and improvement, but even obstruct the goal of preservation itself.