‘The Chicago Manual of Style’: My Life as an Editor in Six Editions

The evolution of the manual over time reflects broader changes in style, culture and technology

1969 was a notable year: Not only did I turn 12, an auspicious event in itself, but the year also saw the first moon landing (I was in summer camp and watched it on a too-small black-and-white TV), the Woodstock Music Festival (I wanted to go but had no older sibling or cousin who might have taken me along), and The Who’s “Tommy” (I somehow convinced my conservative parents that it was a significant work of art).

That same year the University of Chicago Press published the landmark 12th edition of “The Chicago Manual of Style.” I didn't know then how significant a role this book and its successive editions would play in my life. The 12th through the 17th editions have followed me and supported me throughout my publishing career. On Sept. 19, the 18th edition will be released, and it will probably be the last one I use as a professional editor. Between the 12th edition and the 18th, much has changed in the publishing industry and publishing technology, as well as in society and culture, and many of those changes have been reflected in the passing editions of the manual. And so, I’m looking forward to receiving and delving into my copy of the 18th, which I’m sure I will find worthy—even though the cover is going to be a completely inexplicable greenish yellow (I do not approve).

In 1980, on the first day of my first job, I was given a copy of the then-current 12th edition of “A Manual of Style” (it wasn’t called “The Chicago Manual of Style” until the 13th): a standard choice of reference for most editors, but perhaps not that useful for my entry-level job at Rand McNally & Co. editing travel guides. But I kept the manual on my desk and turned to it whenever I could. I read it because I felt I should, but reading it also introduced me to publishing as a profession. It helped me believe that despite the tedium of my entry-level job—checking facts in the “Mobil Travel Guide” against brochures from dusty motels, supper clubs and obscure museums that hadn’t changed since the ’50s—I was still entering into something larger than myself: a tradition, a craft, a guild. A calling.

The fact that I was from Chicago and lived in Chicago made me feel even more connected to the “Chicago Manual.” I had personal connections, too. My copyediting teacher, Margaret Mahan, later became the editor-in-chief of the manual’s 15th edition. The first freelance book designer I worked with was Cameron Poulter, whose design for the 12th edition set the standard for several later editions.

There was a lot of delectable terminology in the manual to absorb: quoin, copyhold, solidus, blind folio, errata, gravure. My favorite terms were recto and verso. “A page,” it says a few paragraphs into the 17th edition, “is one side of a leaf. The front of the leaf, the side that lies to the right in an open book, is called the recto. The back of the leaf, the side that lies to the left when the leaf is turned, is the verso.” This calm, authoritative voice, almost biblical in its cadence, I hold as a chief treasure among the manual’s many treasures.

Although I had been the editor of a literary magazine in college, I found out early in my career that, outside an innate and intuitive sense of grammar, I knew very little about editing. But I knew enough to know what I didn’t know, and I learned quickly that everything I needed to know, I could find in the manual. Take the title of the book, “The Chicago Manual of Style.” Quotes or italics? It’s italics, per section 6.168—though, unfortunately, this publication uses the competing “The Associated Press Stylebook,” which puts composition titles in quotes. I said earlier that I was 12 years old in 1969. Should that have been “twelve”? The manual has a system for that: See section 9.2, but also 9.3, which presents an alternative.

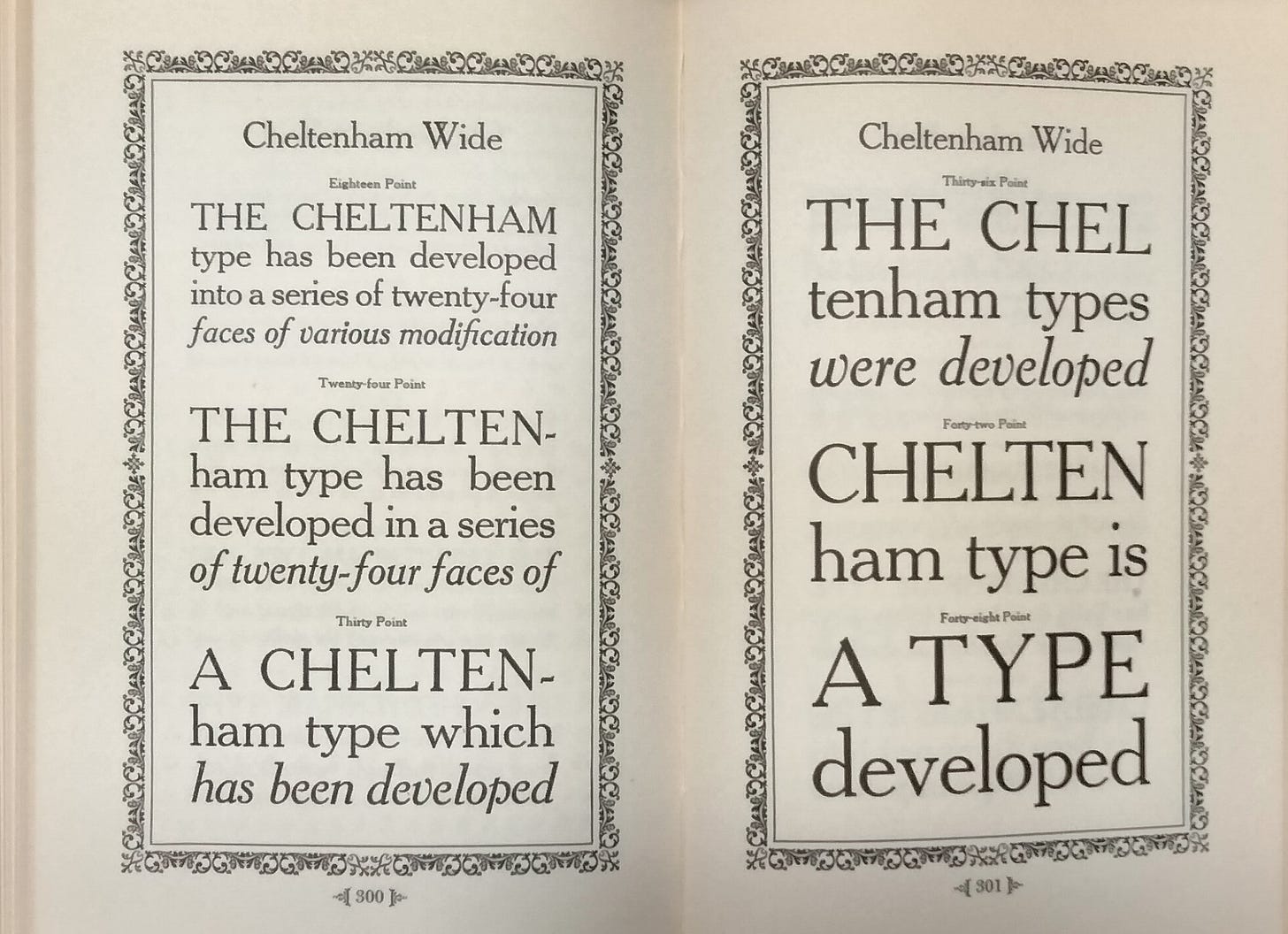

The manual is big and getting bigger. The 17th edition is 1,146 pages; the 18th, we’re told, will be 1,200 pages. The 1st edition of the manual, published in 1906, called simply “Manual of Style” but with an archaically long subtitle, ran only 214 pages, of which only 74 contained actual rules and guidelines. Most of that edition, as with many successive editions up until the 12th, was taken up by an extensive selection of type specimens, examples of how a page of text will look in a particular typeface.

You can tell something about the eras in which each edition was published by looking at the type specimens. The 1906 edition has typefaces such as Cheltenham, influenced by the then-popular Arts and Crafts Movement, and French Old Style, very much of la belle époque, an era then past its prime but not quite at its end. The 11th edition, published in 1949, features a specimen of the gorgeous Bernhard Gothic typeface, one of the then-newfangled sans serif typefaces—the straight-lined, modernist typefaces without ornament seen in signage everywhere.

More recent editions of the manual, by contrast, have a lot less on typography but a lot more on basic rules of grammar and usage. The 15th edition was the first to include an extensive chapter on this topic by lexicographer Bryan A. Garner, perhaps indicating a declining knowledge of grammar in the general population by 2003.

Time passing and trends changing show up elsewhere, also. The honorific “Ms.,” a hallmark of second-wave feminism, hadn’t quite caught on by 1969 for the 12th edition, but had by 1982 and made it into the 13th edition. Evolving technologies such as “desktop publishing” and the “Web” (and “URLs”) made their first appearances in the 14th and 15th editions, respectively. By the 16th edition, an entire appendix was devoted to “digital technology,” and the 17th edition finally allowed us to lowercase the word “internet” in 2017, as the technology went from exotic to ubiquitous.

There are different ways to approach creating a manual or guide to grammar and style: There’s the proscriptive (don’t do that), the prescriptive (do this) and the descriptive (here’s what people do). Although the manual attempts to hold writers and publishers to a higher standard, it does pay attention to the way language is used. In the 18th edition, certain long-standing rules will be changed. The most significant, in my mind, has to do with the long-outlawed use of the singular “they” to refer to one person of any (or unspecified) gender. The fact is, English has never had a good pronoun that is singular but nongendered. Writers and their editors frequently have a hard time wrangling “he or she” and generally try to avoid the construction altogether. But in everyday speech, people have been using “they” as a singular pronoun for quite some time. The 18th edition finally sanctions it.

Indeed, the 18th edition claims to encompass “the most extensive revision in two decades,” touting many changes that reflect current social attitudes:

Every chapter has been reexamined with diversity and accessibility in mind, and major changes include updated and expanded coverage of pronoun use and inclusive language, … new coverage of Indigenous languages, and expanded advice on making publications accessible to people with disabilities. The Manual’s traditional focus on nonfiction has been expanded to include fiction and other creative genres in coverage of topics such as punctuation and dialogue, and the needs of self-published authors receive wider attention.

One thing hasn’t changed, though. If it ever does, I fear my entire faith in the “Chicago Manual” will fall like a castle built on sand. That’s the serial comma, where, in a list of three or more items, the conjunction connecting the final item with the penultimate item is preceded by a comma. In the phrase “apples, oranges, and bananas,” it’s the comma before the “and.” Most of my work has been on the academic side of publishing, and the serial comma is one of those things that separates scholars from journalists (their Bible, “The Associated Press Stylebook,” omits it).

Now, I don’t really think the “AP Stylebook” deserves the bad rep; it’s more complicated than that. And Discourse has applied standard AP style in the editing of this essay (which I find ironic). But the serial comma is dear to my heart. Some call it the Oxford comma, and it's true that it first appeared in the Oxford University Press’ own style manual, “Hart’s Rules,” published as a book in 1904, two years earlier than the “Chicago Manual.” But ask any editor from my hometown, and they’ll tell you: It’s the Chicago comma.

Those outside the publishing industry may dismiss the importance of “The Chicago Manual of Style”—after all, does the serial comma or its absence really matter? Perhaps not, in many cases, though most professional editors have strong, bordering on fanatical, opinions on the subject. But the manual’s broader function is to teach us the way our language is used and how it ought to be used, to promote clarity in communication. And that’s important for any society that depends upon English to shorten the distance between one person and another.