The Causes and Cure of the 2021-2022 Inflation Surge

Targeting aggregate demand growth would be the best prescription to break the fever of rising prices

By David Beckworth

Inflation is back, smashing through central bank target levels, and worrying politicians and the public. Central bankers have been forced to intervene to maintain their credibility, even at the risk of shaky recoveries from the COVID pandemic. There is no free lunch for central banks with weak credibility, but to avoid the risk of throwing the baby out with the bathwater, monetary policymakers should shift from targeting inflation as a proxy for aggregate demand to targeting aggregate demand directly.

The Return of Inflation

Over the past year and a half, inflation has surged to uncomfortably high levels in many economies. This unexpected and sustained rise has caught central banks by surprise after several decades of price stability. In the United States inflation reached 9% while in the Eurozone and the United Kingdom, it climbed to 10%. These are levels not seen since the early 1980s and, as a result, the central banks for these economies—the Federal Reserve (Fed), the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of England—began a very sharp tightening of monetary policy.

This aggressive tightening cycle has many observers worried that the central banks may be spawning the next recession. Central bankers themselves have acknowledged these worries, but believe the threat of inflation becoming unanchored requires drastic action. This willingness to push the economy to the brink of a recession so soon after the pandemic may seem reckless, but it has the support of the public. Polling shows that inflation is the number one concern among Americans, while Europeans are also beginning to see inflation as a top issue. An Ipsos poll taken across 29 countries found that, as of April 2022, inflation had become a bigger concern than poverty, unemployment, corruption, crime and the pandemic. This heightened anxiety has emboldened central bankers in their fight.

This reaction recalls the late 1970s and early 1980s when central banks also responded aggressively to rising inflation with support from the public. In the United States, for example, one polling expert noted in 1979 that “for the public today, inflation has the kind of dominance that no other issue has had since World War II.” That included concerns about unemployment, civil rights, Watergate, Vietnam and the Cold War. This intense public angst created by inflation was what ultimately sanctioned Fed Chair Paul Volker’s recession-inducing mission to subdue inflation in the early 1980s.

This historical pattern of rising inflation becoming a top public concern forces us to acknowledge that people are really averse to rising inflation. But why? What is it about rising inflation that makes it more disliked than other pressing social or economic concerns? This historical pattern should also make us wonder what causes rising inflation in the first place, and what central banks can do to best prevent it in the future. Answering these important questions will help reveal that the easiest way for central banks to avoid many of the current inflation challenges is to directly target aggregate demand rather than inflation itself.

People Really Dislike Inflation

It might seem strange to even ask why people hate rising inflation, since most people do not enjoy paying more for goods and services. However, to fully understand the political salience of this phenomenon, it is important to examine its underpinnings. First, we need to define three key terms: inflation, the price level and relative prices.

Inflation is the growth rate of the price level, which, in turn, is a weighted average of all the individual prices in the economy. Individual prices are formed by forces unique to each price as well as by common pressures affecting all prices. The price of oil, for example, can be affected by wars that reduce supply and drive up price, as we have seen in the Russia-Ukraine war, or by new oil field discoveries that expand supply and lower price, such as the North American fracking industry in the 2010s. These idiosyncratic shocks to oil are called relative price changes because they cause oil prices to change while leaving other prices unaffected. Oil prices, however, can also be affected by global aggregate demand pressures, which affect all prices. For example, the large economic stimulus from U.S. fiscal and monetary policies in 2021 that caused the U.S. economy to overheat and spill over into global spending also affected oil prices.

When inflation is low, like it was in the 2010s, relative price changes are the biggest source of variability in the price level and capture the public’s attention. However, once inflation starts rising, there is a threshold at which the public starts paying close attention to broader price pressures. This is where rising inflation starts becoming a concern and feeds back into people’s decision-making. A recent report from the Bank for International Settlement indicates that this threshold is around 5%, a finding consistent with inflation becoming a top concern this past year as inflation surged past that threshold across most countries. The public, in short, really dislikes rising inflation above 5%.

But why? What is it about high and rising inflation that makes it so despised? One answer is that inflation acts as a tax on money. That is, inflation erodes the purchasing power of money and makes it costly for people to hold money balances. This tax, in other words, is a levy on the key technology—money—that makes it easier for people to trade goods and services. In some developing economies with high inflation, this tax is onerous and impairs market activity. This tax, however, is probably not a big source of people’s disdain for inflation in advanced economies since most forms of money in those economies pay interest that compensates for inflation and the ones that do not—currency and some bank deposits—make up a small share of household wealth.

A more pressing problem created by rising inflation is that it adds noise to the information content of individual prices. Market systems rely on changes in relative prices to inform decision-making and allocate resources efficiently. For example, a relative price increase in oil caused by the Russia-Ukraine war signals to producers to look for more oil, while for households it tells them to cut back on trips and buy more fuel-efficient cars. These relative price signals are what bring supply and demand into balance in a market economy.

However, rising inflation that comes from excessive aggregate demand growth muddies this price signal and makes it harder to know if oil is truly scarcer and, therefore, how to properly respond. For instance, if oil prices are going up because of aggregate demand growth, then oil production costs will also be going up and reduce a firm’s profit margins and its desire to increase oil production. Similarly, if households believe their wages will be going up because the economy is running hot due to strong aggregate demand growth, they may not cut back on trips nor buy fuel-efficient cars.

While much of the oil price surge of 2022 was likely due to the Russia-Ukraine war, some of it was also the result of the strong aggregate demand growth flowing out of the U.S. economy. Distinguishing between these two types of price pressures is difficult for businesses and households when making economic decisions. This signal-extraction problem rises with the level of the inflation rate and, as a result, makes economic decisions even more challenging during periods of inflation surges such as the last year. People really dislike this uncertainty.

An additional problem created by rising inflation is that it increases everyday transaction costs. Households must spend more time monitoring prices, looking for sales and managing budgets. Additional monitoring costs also arise for firms as they must expend extra time checking raw material prices, labor costs and other prices. In addition, households and firms must pay closer attention to national economic policies and the implications for inflation. Inflation is a tax on the public’s time, and they resent it.

Another feature of rising inflation is that it affects everyone. Not everyone will lose a job during a recession, but everyone will feel the bite of rising inflation. Some groups, to be clear, experience more inflation than others. Poorer households tend to suffer greater inflation, as seen in the United States and in Europe over the last year, and some minority groups are especially harmed by rising inflation. For these households, their incomes do not keep up with inflation, and they find it harder to afford basics like food, transportation and shelter. This uneven bearing of costs adds further distaste to the inflation experience, but no one is immune to it. Everyone must contend with the challenge of rising inflation at some level, making it a universally shared frustration.

These key reasons why rising inflation is so disliked by the public help explain why it has become a top concern across many countries. This ire, in turn, has emboldened central banks to take drastic measures to rein in inflation even at the risk of creating a recession. Given this strong dislike of rising inflation, it is important to understand what causes it and what can be done to avoid it in the future.

The Causes of Inflation

As noted above, there are both relative price changes created by idiosyncratic shocks and broader changes in the price level caused by growth in aggregate demand. The idiosyncratic shocks are often called supply shocks and affect the productive capacity of an economy. Many of the developments we saw in the pandemic—fewer people working, lower oil production, reduced global shipping—are examples of negative supply shocks that reduce the availability of goods and services and, as a result, make them more costly. Positive supply shocks work in the opposite direction: They provide more goods and services at a lower cost.

If supply shocks are big enough, they can temporarily affect the inflation rate. The flow of oil, as noted above, has been impaired by the Russia-Ukraine war and is an example of a negative supply shock that has temporarily raised the inflation rate in both the United States and Europe. Many supply shocks, like the ones from the pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war, are temporary in nature and, therefore, should not have a permanent effect on inflation.

The other source of inflation is aggregate demand or, equivalently, the level of current-price spending. Its growth is determined by the mix of fiscal and monetary policies, but occasionally can be influenced by other shocks like a financial crisis where households quickly cut back on spending. Since the 1990s, most advanced economies have chosen their central banks to be the final arbiters of aggregate demand growth and, as a result, monetary authorities have typically determined the growth path of aggregate demand and the trend inflation rate.

Central banks have been fairly successful over the last 30 years in maintaining stable aggregate demand growth, but there have been times when they have failed. Most recently, the Fed allowed the level of aggregate demand to rise above its pre-pandemic trend starting in the fourth quarter of 2021. This gap has been growing and indicates that a significant part of the 2021-2022 inflation surge in the United States has been due to excess growth in aggregate demand.

Rising inflation, then, can be caused by both negative supply shocks and excess aggregate demand growth. Inflation-targeting central banks need to know in real time how each of these factors are influencing inflation for them to successfully deal with it. This understanding stems from the fact that central banks cannot fix inflation caused by negative supply shocks without making matters worse. They can only address inflation in a stabilizing manner that is caused by excess aggregate demand growth.

Should the Fed, for example, tighten monetary policy in response to the rising inflation caused by supply shortages coming out of the Chinese lockdowns and Russia-Ukraine war, it would not solve the underlying supply disruptions and only further impair an economy already harmed by the supply shocks. On the other hand, the Fed can fix the rising inflation caused by excess aggregate demand growth that came from the $1.9 trillion American Recovery Package. In that case, the Fed solves the underlying aggregate demand problem by tightening monetary policy and, in the process, putting current-price spending on a more sustainable growth path.

The distinction, then, between rising inflation caused by supply shocks and inflation caused by excess aggregate demand growth is essential for successful central banking. But therein lies the rub: It is impossible to know this distinction in real time.

This uncertainty is well illustrated by the Fed’s confusion over the 2021-2022 inflation surge. Initially, Federal Open Market Committee members saw the rising inflation in 2021 coming from supply shocks and, consequently, were slow to tighten monetary policy. In hindsight, however, Fed officials acknowledged that excess aggregate demand growth was also a part of the inflation surge and wished they had tightened sooner. Another example is the ECB’s response to rising inflation in 2011. ECB officials tightened monetary policy in response to this period’s rising inflation as if it were caused by aggregate demand growth when, in fact, it was caused by a relative shortage of commodities driving up their price. This confusion led to a collapse in aggregate demand and helped create a sharp recession in Europe.

The Cure for Inflation

So what are central bankers to do? How can they overcome this knowledge problem? One popular suggestion is to directly target aggregate demand growth rather than inflation. Instead of trying to divine what part of inflation is due to aggregate demand shocks and should be managed, we should look directly at aggregate demand itself. This approach cuts out the middleman of inflation and goes straight to the underlying source of inflation movements that is amenable to monetary policy.

The amazing thing about this approach is that it provides a clever workaround to the central banker’s knowledge problem. That is, by forcing monetary authorities to focus on stable aggregate demand growth, it keeps trend inflation anchored but allows for temporary inflation caused by supply shocks. This is the very outcome desired by inflation-targeting central banks.

The next question, then, is how do we measure aggregate demand? There are different ways to do it, but one well-known method is to use nominal GDP (NGDP). NGDP measures total current-price spending on final goods and services in the economy—it is the economy we see in the real world. Put differently, NGDP growth has both real GDP growth and inflation embedded in it. Using this measure creates a monetary policy framework that is called NGDP targeting.

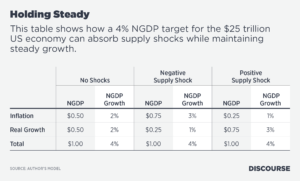

The table below provides an illustration of this approach for the U.S. economy. It assumes the U.S. economy is at $25 trillion and the Federal Reserve is targeting NGDP growth at 4% a year, reflecting the Fed’s desire for 2% inflation over the long run and a belief that real GDP growth potential is 2%.

The first column in the table shows what happens if there are no shocks. NGDP grows 4%, or $1 trillion, and the spending is evenly split, as planned, between higher prices and real economic growth. The second column shows what happens when there is a negative supply shock. The economy still grows $1 trillion, but now three-fourths of that spending goes to higher prices and only one-fourth to real economic growth. The third column shows what happens when there is a positive supply shock. The economy, again, grows $1 trillion, but now three-fourths of that spending goes to real economic growth and one-fourth to higher prices. In all scenarios, total dollar spending stays the same while the inflation rate is allowed to temporarily move around in response to supply shocks. This is how NGDP targeting allows for price fluctuations caused by supply shocks while still aiming for a stable trend inflation rate.

Note that we see in this illustration an average inflation rate across the three scenarios of 2%. If the supply shocks are assumed to be temporary and evenly distributed, then this 2% average inflation outcome should hold up over time. That means by pursuing an NGDP target, a central bank is also effectively targeting an inflation target over the medium run. NGDP targeting, in other words, is a two-for-one deal that gives central banks the inflation cure they are seeking.

Even though no central bank currently targets NGDP, this framework can still be useful in understanding the inflation surge of 2021-2022. As noted above, some of this inflation was due to supply shocks and some to excess aggregate demand growth. In real time, it was hard to know the breakdown between these two sources, and this lack of understanding contributed to the Fed “falling behind the curve” with rising inflation.

One way the Fed could have cross-checked its inflation views during this time was to look at NGDP relative to its pre-pandemic trend. This trend provides a good approximation to where NGDP would have gone in the absence of the pandemic, given potential real GDP and the Fed’s 2% inflation target. Figure 3 shows that after a sharp decline in NGDP, the Fed was allowing rapid catch-up growth to the pre-pandemic trend. By the third quarter of 2021, NGDP had fully returned to this trend. The Fed should have started the tightening of monetary policy around this time to avoid excess aggregate demand growth. It did not, and by the second quarter of 2022, NGDP was approximately $1 trillion above the pre-pandemic trend. This large NGDP gap implies the economy was running hot and, in turn, that a significant part of the inflation surge was due to excess aggregate demand growth.

By contrast, the Eurozone’s NGDP has had a slower recovery from the crisis and only reached the pre-pandemic trend by the second quarter of 2022. That means the inflation surge in Europe was caused largely by supply shocks up to this point, and that the ECB had less need to tighten monetary policy as aggressively as the Fed. NGDP would have provided a great cross-check for both the Fed and the ECB in understanding the inflation challenges they faced over the last year, emerging from the pandemic’s unprecedented and bewildering economic turbulence.

To be fair, NGDP data comes out with a lag, and therefore it may be tough to discern in real time where NGDP is going. For this reason, central banks should look at forecasts of NGDP. In a recent Mercatus Center working paper, Pat Horan and I show that had the Federal Open Market Committee been looking at monthly NGDP forecasts, they would have seen signs to tighten back in 2021. Similar findings are shown in this Dallas Fed note. NGDP forecasts, then, provide a useful way to cross-check the stance of monetary policy.

The Future of NGDP Targeting

This article has made the case that targeting aggregate demand growth is the best cure for rising inflation. It focuses the attention of monetary authorities on the underlying cause of trend inflation while allowing them to see though inflation caused by supply shocks. This approach is not a new idea, but recently garnered a lot of attention following the Great Recession of 2007-2009 and now is showing its relevance again in the midst of the inflation surge of 2021-2022. It is a versatile and robust monetary policy framework that would have been helpful over both periods.

No country has ever explicitly targeted aggregate demand growth, but now that central banks are doing regular reviews of their frameworks it should be a top contender for replacing existing approaches to monetary policy. As noted earlier, NGDP targeting also acts as a medium-run inflation target and would make it easier for central banks to avoid inflation crises like the present one. If implemented properly, it would lead to greater monetary stability and fewer inflation crises across the world. Here’s hoping this is the future of central banking.