The Case Against Nudging and the Paternalistic State

Shruti Rajagopalan talks with Mario Rizzo and Glen Whitman about the downsides of newer, supposedly softer forms of paternalism

By Shruti Rajagopalan

Mercatus Center Senior Research Fellow Shruti Rajagopalan recently spoke with Mario Rizzo and Glen Whitman about their new book, Escaping Paternalism: Rationality, Behavioral Economics, and Public Policy. Rizzo is an associate professor of economics, director of the Program on the Foundations of the Market Economy, and co-director of the Classical Liberal Institute at New York University. Whitman is professor of economics at California State University, Northridge. This transcript, as well as the audio of the conversation, has been slightly edited for clarity.

SHRUTI RAJAGOPALAN: Welcome to Mercatus Policy Download. My name is Shruti Rajagopalan, and I’m a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. Today I’m really excited to discuss a new book called Escaping Paternalism: Rationality, Behavioral Economics, and Public Policy with the book’s authors, Professors Mario Rizzo and Glen Whitman. Professor Mario Rizzo is an associate professor of economics at the NYU economics department and the co-director of the Classical Liberal Institute at the NYU School of Law. In fact, we were supposed to have this book discussion in person at the NYU School of Law, but we moved it online to cope with the COVID pandemic. Mario, welcome to the show.

MARIO RIZZO: Thank you very much for inviting us.

RAJAGOPALAN: We also have with us the other author of the book, Glen Whitman. He is a professor of economics at California State University, Northridge. Welcome to the show, Glen.

GLEN WHITMAN: Thank you for having me.

RAJAGOPALAN: I’m really excited to speak with both of you about the book. The book covers several areas. First, you have reframed the big questions of behavioral economics, in particular the question of rationality. Following from your critique of behavioral economics, the book also discusses a lot of the policy recommendations made by behavioralists, in particular what is now called new paternalism or nudge paternalism or soft paternalism. Can you talk a little bit about how and why the arguments of this book came about? Mario.

RIZZO: Shall I start? Well, around 2002, I saw an article in the American Economic Review’s papers and proceedings by Cass Sunstein and Richard Thaler called “Libertarian Paternalism.” Obviously, the juxtaposition of those two words caught my attention. After I read the article, I became quite annoyed by it. And so, along the lines of the article, I began to think about some of the issues that they had discussed and wrote to Glen, because we had been co-authoring things for some time, about a possible refutation or some sort of article on the issue.

WHITMAN: The basic argument that they were making then, and that they still make now, is that contrary to classical models used by economists that treated people as being fully rational, that real people, as demonstrated by behavioral findings, were not fully rational. And that meant that there was an aperture for behavioral interventions by the government to try to improve people’s decision-making. And so, it was a kind of new argument for paternalism.

The old-school paternalism was to say, “We don’t particularly care about your preferences. We think that there’s some objective notion of the good that we’re going to make you comply with.” So your classic paternalism would have been, say, the temperance movement. This more modern form of paternalism was aimed at saying, “Look, you’re making decisions that are not good, even in terms of your own values or your own preferences. And so, we can intervene in targeted ways in order to improve your decision-making.” So that’s what Mario and I were reacting to.

RAJAGOPALAN: There are all sorts of arguments made in favor of sin taxes. Of course, in the academic literature, it starts with, one needs to calibrate the tax just enough to nudge the individual closer to their true outcome, or what would be their true number of cigarettes per day or how many fries they would like to eat per day or something like that. And sin taxes are usually compared to outright bans, which is banning soda altogether or banning fatty foods altogether. So sin taxes seem to be, like, this great compromise solution. Can you walk us through the connection between behavioral paternalism, sin taxes, and what is this hybrid monster we actually have in the area of consumption taxes today in the economy?

WHITMAN: I think the first question that you have to ask is, “Is any correction required?” Before we start talking about the policy itself and the dangers of the policy and whether it can be calibrated right and so on, you have to say, “Look, where does this presumption come from that people must be fixed?” And often it is driven by a kind of gut reaction. You look out there and say, “Well, there are fat people, too many fat people, and therefore we need to stop them from eating too much.” But that, of course, is not science-based. And it really, I think, comes from a more old-school paternalist impulse to say that there’s an objective way to behave, and if you’re not behaving in that way, if you’re not maximizing your lifetime or your number of life years, if you’re not remaining healthy, that that’s somehow an irrational decision.

And that’s not even true under the traditional conception of rationality used in neoclassical economics, nor is it true under the notion adopted by behavioral economists, nor is it irrational in the more inclusive notion of rationality that Mario and I put forward in the book. People have subjective preferences, and they are allowed to indulge them. So if you’re going to intervene, you need to be able to show that people actually are making some kind of an error in the implementation of their true preferences.

If people, say, decide they’re going to start a diet next month, and then when next month comes, they decide they’re not going to do that diet after all, and they continue to eat the way they did before, does that necessarily mean that somebody is making an error? It means they’re behaving, arguably, in a kind of inconsistent way, but there’s no reason for that to justify our saying, “And therefore the correct way for them to behave was for them to have carried through that plan to start a diet.” We have to respect people’s subjective preferences, whatever they might be.

Now, once you’ve decided that, let’s say we, for the sake of argument, say, “Well, we know it. We know that people are making a mistake in that regard.” Then you start to get into all of the more practical issues of, okay, what’s your policy going to be? What is the right size of the sin tax? How big of a bias are you going to try to counteract with that sin tax? How are you going to measure the disparate effects on different people, since even if you admit that there are a large number of people who are, say, eating too much, there are also plenty of other people out there who are doing just fine, who are happy with their eating choices, and they are all going to end up having to pay that tax as well.

And as a result of that tax, they may reduce the amount of their consumption to below what would be an optimal level for them. So that’s something that has to be taken into account, too, and so on and so forth. It is not nearly the simple proposition that we are led to believe.

RIZZO: The mystery in all of this is that behavioral economists have often said, “Oh, well, we recognize that people will be, say, eating sweets or not exercising or whatever the behavior is because they get a certain utility, because they get a certain pleasure from the sweet, so they get a certain pleasure from not engaging in strenuous activity, and so forth.” We recognize all of that. And that goes into our notion of what their true preferences are.

But when it comes to the actual practice, all of that’s ignored. It’s treated as if any deviation from what I would call the health maximum is a problem of lack of rationality or some sort of bias on the part of individuals. And that’s because it’s very difficult to measure the degree to which people’s behavior is a result of some bias or it’s a result of some preference with respect to the sin good, that it may give them some utility. So that’s an important factor. And it puzzles me often because they say very specifically that they include the pleasure of the sin activity as one of the valid reasons for engaging in the activity.

RAJAGOPALAN: I want to pick up here with one of the examples that is very famous from both the Nudge book and a lot of other work that Thaler and Sunstein have done. And this is in favor of default rules. And the particular example I want to pick is default rules for retirement savings. So, their argument’s quite simple: it is that because of a present bias, people don’t save enough for the future. This is seen from both empirical findings in behavioral economics, as well as survey data on how people themselves respond to whether they would have liked to have saved more for the future, and those sorts of questions. So, a simple solution that is presented by Thaler and Sunstein in Nudge is to change what they call the choice architecture. Right? So, it’s a simple enough change.

The old rule would have been that the employee was required to fill out a single form or a bunch of forms and submit them to the employer to enroll themselves in some kind of retirement savings policy with the firm. Now, if you change the default rule—that is, now, people need not opt in; they are automatically enrolled. But instead, they need to fill out forms to change their enrollment policy, or in fact to opt out, right? And this is just a change in the choice architecture. It’s not an actual change in the choices given to the individual.

So, in a sense, it seems incredibly innocuous, right? It’s probably going to increase savings because they will use a different bias, which is the inertia bias to fix the problem of people having too much present bias. And on the face of it, it doesn’t seem very oppressive because, at any point, technically, an individual can change the retirement options. But you argue against even these policies of default rules, which are just changing the choice architecture. You say that they look innocuous, but they have a whole range of hidden problems and paternalism sneaked into it. Can you walk us through that for this particular example?

WHITMAN: Well, first, I think it’s important to frame the issue here because we are not necessarily opposed to the idea that specific employers might decide, under their circumstances, that it makes sense for them to shift the way that they enroll people in savings plans or don’t enroll people in savings plans. But, in keeping with the behavioral paternalist approach, often the authors that we’re engaging with here don’t always clearly distinguish between who is the decision maker. They’ll refer to it as choice architecture, and they’re not asking, “Well, who is the architect?”

We would argue that there’s a big difference between, on the one hand, having a competitive market of many architects making choices affected by supply and demand forces, affected by the other parties with whom they are interacting, and on the other hand, having a government policy that is specifically designed to lock all of us into the same choice architecture.

So, that said, we go to the issue of, is this necessarily a good idea? It is not nearly as simple as these authors would have us believe. It is not necessarily the case that we will always have the effect that we hope in terms of increasing people’s savings, nor is it obvious that that’s going to necessarily be a good thing.

RIZZO: I think there are two issues, aside from the “who is the choice architect” issue, which I think is very important. First issue is, why does there seem to be an effect of the default of automatic enrollment? And secondly, whether that effect is as unambiguously positive as Sunstein and Thaler and others have claimed it to be. The first question goes to whether the effect that we’re seeing—and we are seeing an effect, that more people are enrolled in these programs, 401(k) retirement programs, under automatic enrollment than under the previous regime of opting in. Is that basically because of some sort of behavioral effect, or is it explicable in more ordinary, shall I say, neoclassical or inclusively rational terms?

As to that question, we did a fairly comprehensive examination of the 401(k) issue. I think the appendix in the book is about 27 pages. And what we find is that there are many factors that occurred simultaneously with automatic enrollment that seemed to be more powerful as explanations for the effect. One of them is, of course, the idea that if the default that your employer establishes is enrollment, that is oftentimes equated as a recommendation from a party which is presumptively more knowledgeable than you are about the advantages of a particular employee benefit, is taken as a recommendation to enroll. So, in effect, what that is is a partial overcoming of the information problem that people have in making the decision, a financial decision to enroll, not enroll. They’re getting help by, in effect, expert advice.

Secondly, simultaneously with this development has been a tremendous increase in the advice and information offered by employers to employees about retirement options. And so, people are much more informed now than they used to be about the advantages of these policies. We go through the various behavioral explanations that the behavioral economists have offered for why the default works and found each of them wanting. And then, so, we rely mostly on more standard explanations. I could talk about the question of whether the effect is unambiguously good, but I’ll hold off from that.

RAJAGOPALAN: Just to follow up on that. There are some other issues related with the default rules. Are you at all worried about individuals changing their behavior once they adjust to the default rule? That is, now that everyone knows that there is automatic enrollment, are you at all worried about unintended consequences, like offsetting behavior by the employer, offsetting behavior by the employee, and what that does to the rest of their, so to say, life behavior related to financial savings and their financial health?

WHITMAN: Yes, absolutely. That’s one of the topics that we discuss specifically in that chapter appendix that Mario was talking about. This happens in a variety of ways. One of the best-known ways is that when people are defaulted into a savings plan, there also has to be a default savings rate. And sometimes that default savings rate won’t necessarily match what people would have chosen on their own.

And so, interestingly enough, while you can cause more saving by the people who otherwise either would not have enrolled or would not have enrolled as soon, you can actually reduce the amount of saving that happens from people who otherwise would have enrolled on their own and perhaps would have chosen a higher level of savings. So that’s one example. And it turns out, empirically, that those effects seem to cancel out in terms of the overall amount of saving that takes place across employees.

Another thing that can happen is that people can save more in their 401(k)s, but then they can adjust in other ways by reducing other forms of saving that are not affected by the default rules, or by incurring more debt—say, buying more cars or buying larger cars, or by incurring more house debt or more credit card debt, or what have you. And so, it doesn’t follow that by increasing their savings in retirement plans we’re necessarily increasing their savings overall or improving their financial situation on net.

RIZZO: Yes. That’s an important factor because, obviously, the ultimate goal of all this is to increase savings. And the unintended consequences, the indirect consequences, are ones which are frequently ignored in the sort of celebratory attitude that people have toward this default business. And so, I think that that’s an important factor to consider: What is the overall effect? And we try to outline that in the appendix.

WHITMAN: I’d like to add on to that. In addition, there’s the background assumption or a background presupposition, which we’ve all been working with so far in this conversation, even, which is that we must increase the savings rate, that it is a given that that is an unalloyed good. We take a subjectivist perspective, as most economists do, saying that, “Look, it’s ultimately a matter of individuals’ preferences, including their time preferences—their willingness to delay gratification, and so forth.” And those should matter. And those are the relevant standard for deciding how well people are doing.

The behavioral economists have challenged that, not by challenging subjectivism, not by challenging the idea that you can decide what is best for you, but rather, challenging the idea that people are necessarily acting in concert with their own preferences about time and about the delay of gratification. And we think that that argument turns out to have feet of clay. And the reason for that is because they have based their argument of the idea that people are violating even their own preferences on the idea that people display time inconsistency.

Loosely, what that means is that people will make different choices about a tradeoff depending upon whether it’s close to them in the present or far away in the future. So, if you’re choosing between $10 today and $11 tomorrow, you should make the same decision for that choice as you would for $10 a year from now and $11 in a year and a day from now. And when they don’t make the same choice, when people instead say they would choose $11 when it’s a year and a day from now, but then, when it approaches the present, they would reverse that decision and instead choose the $10 over the 11—so they choose the smaller sooner over the larger later amount—they say, “Well, that’s a kind of inconsistency. And inconsistency does not fit with our notion of rationality in economics.”

And so, they use that as the aperture to say, “Okay, in that case, people must be making a mistake, and that means there’s room for us to step in and try to correct that mistake.” And so, that is the type of argument that we engage heavily, especially in the early chapters of the book, to say that actually is a non sequitur. Even if you believe that people are behaving inconsistently in that way, that does not give the analyst or the politician the right to decide which of those tradeoffs is the correct one, to decide which one is better for your preferences.

RAJAGOPALAN: There’s this question that keeps popping up throughout the book—this comes from the language that is in the behavioral economics literature—about true preferences. And—Glen, you just hinted to that—is it my true preference to really save more, or am I just seeing right now that my true preference is to save more in the future? But the moment I’m encountered with the choice of saving more, I actually don’t want to save more. I want to take that cruise or I want to buy that car. Right?

So now there’s the question—there’s, of course, the philosophical question of what is someone’s true preference, but there’s also the more practical matter of who decides what is someone’s true preference. And you have a range of arguments called the knowledge problems faced by the paternalists. This is, of course, a nod to the famous hierarchy and notion of the knowledge problem. Can you walk us through some of these problems?

WHITMAN: I’ll jump in on that one and say, the first step is you have to realize, of course, that just because somebody says something doesn’t mean that it’s true. People may say, “Oh, I really should lose some weight” or “I really should stop smoking” or what have you, but actions speak a lot louder than words. Now, what the behavioral economists have said is, “Well, maybe even the actions don’t speak very well. Maybe your actions don’t accurately represent your preferences.” And that may well be true, but that doesn’t mean that we should suddenly trust everything that people say.

There’s a social desirability bias as well. People say what they think they’re supposed to say or what they know that other people want to hear. Set that aside, even supposing that we have an individual who has a kind of inconsistency, and even, following the behavioral economists, we say that that reveals that there must be an irrationality there, there are still a lot of steps in identifying what the true preference is that somebody has in order to get them closer to it. So, we have to say first of all, what was their true underlying preference? And if the things that people say don’t reveal it, and the things that people do don’t necessarily reveal it, then what is going to be their source of information that’s going to give them this infallible knowledge of what it is that people genuinely want in their true heart of hearts? So that’s the first thing.

And then the second thing is, even if you know that, then you have to know what is the extent of people’s bias. In other words, how strong is that effect that is somehow pulling them away from what it is that they truly want? And then you also have to know, well, is it possible that the individual has already done some degree of self-correction? They may have opted into some kind of automatic deduction plan. They may have joined a Weight Watchers club. They may have done all manner of things to shape their environment in such a way as to get what they perceive as a better choice.

And so, what we have to know is, how far away are they operatively in their real-world behavior from their actual preference? And then we have to know, okay, for a given intervention that might be designed to fix that error, okay, well, how effective is that intervention going to be? And is it possible that the intervention will, to some degree, cause an unraveling of those choices that an individual has made for himself to structure his environment or in some other way shape his own behavior?

And going even a step further, we also have to realize that most policies that we have are going to be one size fits all. And so, that means we have to start worrying about heterogeneity in the population. How are people’s true preferences different? How are their biases different? How are their self-corrective measures different? And when we intervene, is it possible that by helping some individuals, we’re actually going to be harming other individuals? And in that case, how are we going to weigh those benefits and harms against each other? And we argue that this knowledge problem faced by policymakers means that they’re very unlikely to have the answer to any of those questions, to say nothing of all of them.

RIZZO: I should add a couple of more general things. First of all, I think it’s important to take seriously this notion of true preferences as the fundamental characteristic of this new form of paternalism. Because unless we do so, it is easy to fall into the trap of saying, “Well, all they’re trying to do, all these paternalists are trying to do, is achieve goal X, defined in some quasi-objective terms.” But that’s not what new paternalism or behavioral paternalism is about. It’s about affecting your underlying preferences.

And that’s a far more difficult thing than the old paternalism, which said something like, “Well, you shouldn’t drink. We don’t care what your true preference is regarding drinking. We’re just going to stop you from drinking. So we’re going to make drinking illegal, and that’s the end of it. Simple.” Simple at least in concept, but, of course, it produces Prohibition with all its problems. So that’s very important to emphasize. This is the unique characteristic of behavioral paternalism, the search for true preferences.

The second general thing I want to say is that we can look at true preferences in a slightly different perspective. Operationally, true preferences are the preferences that people would have if there were absolutely no biases. So, it’s a residual category. Now, there are at latest count approximately 200 biases, which are listed on the Wikipedia page of cognitive biases.

So, in any realistic situation, in order to discover true preferences, we’ve got to go through the list of biases and ensure that none of the biases, or at least none of them to any reasonably important extent, are present in a given situation, in order to exclude all of that and then to discover what the purified preferences are of people. I mean, it’s another way of looking at it, and it’s a way of looking at it that’s quite realistic because, in effect, that is their definition of true preferences—the preferences people would have if there were absolutely no biases. And with 200 biases, you can see how taking that seriously is a very difficult task.

RAJAGOPALAN: That’s an old way of phrasing it because it sounds like the way humans would behave were they not human at all, is what they’re really saying about human behavior.

RIZZO: Well, that is an important element. The behavioral economists have complained since the existence of behavioral economics that the neoclassical economic man is totally unrealistic. It’s a caricature of what people are like. But then, in their normative prescriptions, they want to turn real-world individuals into neoclassical agents.

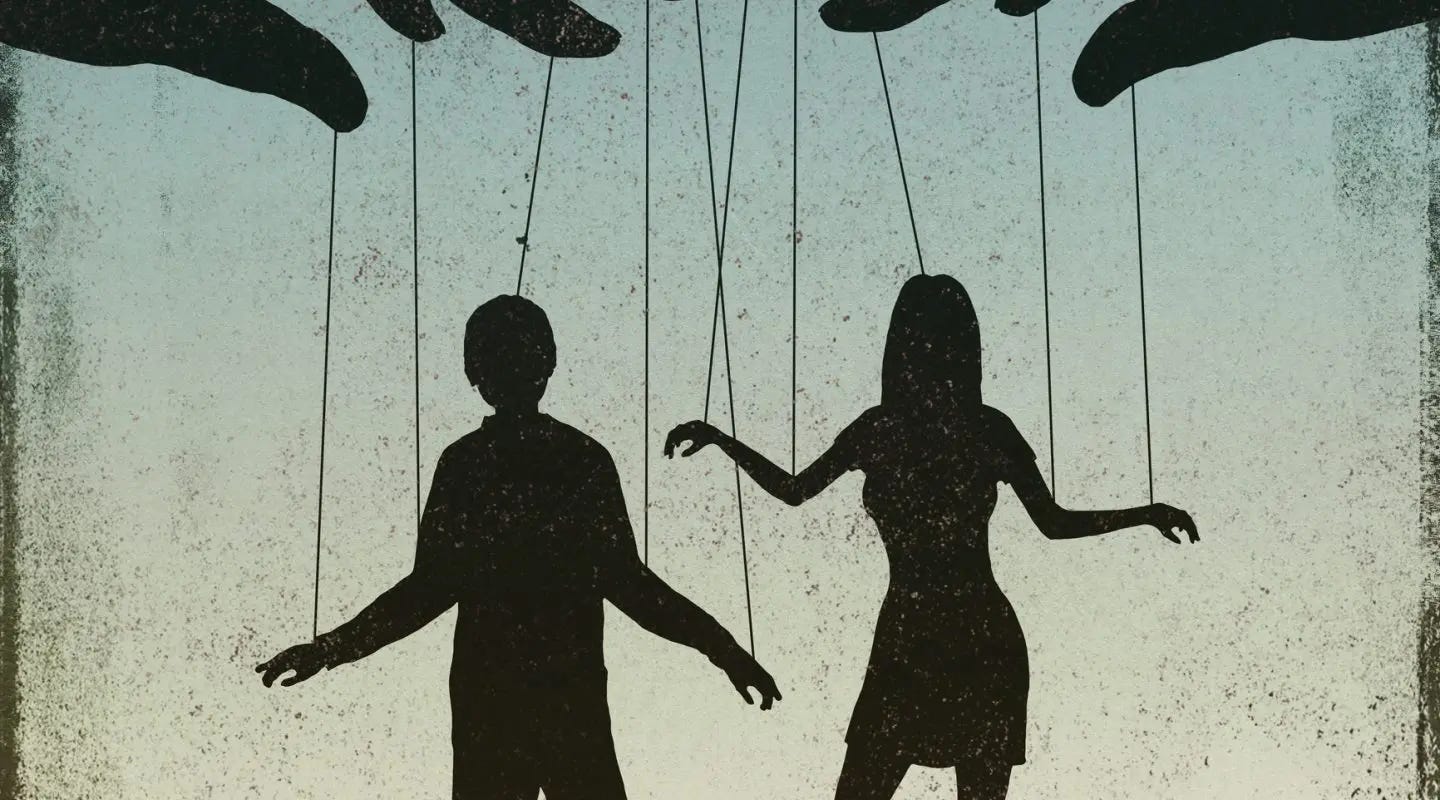

There are two senses in which behavioral economists view human beings as puppets. One is to control them, to ensure that they do what the behavioral paternalist thinks they ought to be doing, acting in accordance with their true preferences. But also, it turns them into the very puppets or caricatures that neoclassical economics is being criticized for conceiving human beings as. It wants them, in effect, to become neoclassical agents, to decide things as the neoclassical rational agent would.

RAJAGOPALAN: So, now there are two sets of issues going on with nudge paternalism. The first is, we are trying to find the accurate behavior or the true preferences and actions of the individual agent. But there’s a second problem, which is that the paternalists themselves are human, one could assume. Right? So, what are the sort of problems that they face when they are trying to nudge people toward their correct behavior? One is the incentive problem, which talks about all the public-choice-theory sort of issues that creep into paternalism, and this has mainly to do with tobacco and vaping and those kinds of policies.

And the other is slippery-slope policies, where even well-intentioned or seemingly well-intentioned agents—once they start nudging you in one direction, that is not the end of the matter. It is not the end of the matter that you say, “We just change the default rule,” or “We just give you the calories and tell you how much to consume.” The paternalism snowballs and turns into a whole other beast, which looks a lot more like the old paternalism than the innocuous libertarian paternalism. So, can you talk a little bit about these critiques, which are specific to the behavior of the paternalist?

RIZZO: The question of incentives is important because a lot of the book revolves around the idea that if people bear the consequences of biases that they might possess, that that bearing of consequences will cause the biases to erode. And there’s plenty of evidence of that, and we go through that in the book. The problem with the political system is that if decision makers are biased in the political system, they do not get a feedback, in the way you get with making private decisions, that will cause the biases to erode.

For example, any bias that a voter might have in assessing public policy does not have a feedback. There is not a feedback loop that causes them to bear the consequences of their poor policy decision based on the bias that they exhibit in their voting behavior. And so, this is part of what Bryan Caplan calls rational irrationality. And this is an important element that makes the political system far more vulnerable to biases than the market system.

For example, so-called availability bias. You see a certain problem is manifest in some spectacular event. And then, for example, there may be some spate of airline accidents, or there may be some spate of a particular type of drug side effects, very, very visible, etc. And so, people may be led on the basis of that to advocate policies which are extreme and unwarranted regulatory reactions to these problems. And there’s no feedback mechanism in the sense that an individual subject to bias, voting for candidates who approve of these policies, doesn’t suffer the consequences of the overregulation individually. Now, if a person makes a mistake because of some bias on a product to buy in the market, there is a feedback mechanism because they’ll get a product which is not as good.

WHITMAN: I would also add on the example of vaping as a nice example of the kind of crisis-driven decision-making that Mario is talking about. In the case of vaping last summer, we saw the emergence of a kind of new health crisis related to vaping. It was vaping-associated pulmonary illness, or VAPI. And it seemed to be a lung condition that was manifesting entirely in people who had been smoking vapes. And the policy response to that crisis, as people started to die from this, was to immediately go to the route of bans, and specifically bans that were entirely disconnected from what appeared to be the real cause of VAPI.

As they looked into it, it appeared that the most likely culprit—and indeed, one that was validated by the CDC later—was vitamin E acetate, which was an additive in vape capsules that appeared almost entirely, if not entirely, in the black market. Nevertheless, the response to this in many municipalities was to ban flavors, ban flavored capsules, even though there was no connection whatsoever between flavoring and the most likely culprit of vitamin E acetate. So, it was kind of a panic-driven response. “We’re going to ban it temporarily—all vapes we’ll ban—and then even after that, we’ll keep the ban on flavored vapes, even though there’s no connection whatsoever.”

And what this reminds us of more generally is that the tone of behavioral paternalists from the beginning has been to say, “We are going to be evidence-driven. We are going to advocate policies which are based on research and a careful consideration of all the factors involved to try to find out what people’s true preferences are.”

One phrase that we love that was used in one of these articles was “a careful, cautious, and disciplined approach.” And that’s a nice ideal. But I think all of us live in this political system that we have, and we know that that is an ideal that is very, very rarely achieved. The reality is that policymakers, including voters and politicians and bureaucrats, move forward very quickly with policies that are not necessarily fully justified based on the evidence and are often driven by a kind of action bias—a desire to do something, even if that something is entirely disconnected from the problem that you’re trying to fix.

RAJAGOPALAN: Yeah. So, if I can say it the way you say it in the book, in the language of true preferences, it’s no longer about the true preferences of the individual agent. It’s just about the true preferences of the paternalists. And they would prefer that you not vape. And that’s the end of the matter.

RIZZO: Right. Yes.

WHITMAN: I think what’s important to realize is that there’s sort of an academic debate, and then there’s a policy debate. Now, at the academic level, the behavioral paternalists are very clear about the fact that they are not old-school paternalists, that they really do only care about maximizing your own preferences, making you better off by your own lights. And much of our argument through much of the book is directed at that kind of pure Platonic form of the argument. But as soon as you enter the realm of politics, things get messy. We know that’s true.

And so, when it comes to a particular policy that is being promulgated, it may be supported by a combination of people supporting it for different reasons. It may be partially supported by some behavioral paternalists who think, “Well, maybe people are making an error, a cognitive error, that’s causing them to betray their true preferences.” But they may be supported by some more traditional, old-school paternalists of the “you’re not supposed to get pleasure from this” variety that Mario was just talking about.

And they may also be supported by some people who have an old-fashioned financial interest in shaping people’s behavior, such as, for instance, tobacco companies, which have an interest in keeping out upstart competitors from new vaping companies. They would rather you continue to smoke either old-school cigarettes or their variety of the vaping capsule or their variety of the vaping device—the one that they produced rather than the one produced by the entrants into the market. And so, you get this conglomeration of different bases of support for a paternalist policy. And interestingly, they can all hide behind the fig leaf provided by a behavioral paternalist argument.

And so, that’s why one of the things we say in the book—we draw on the economist Bruce Yandle’s idea of bootleggers and Baptists. Bootleggers are the traditional special interests that do things for financial reasons or support regulation for financial reasons, and the Baptists are the true believers who support a regulation—usually a paternalist regulation—because they think it’s just the right thing. So, you can think of them as your old-school paternalists. And what we say is that in the modern era, I think we’re starting to observe the emergence of a kind of bootlegger-Baptist-Baptist coalition. It’s two different varieties of Baptists. You have your old-school paternalists, and you have a new variety of paternalists that comes from this seemingly scientifically motivated behavioral-paternalism perspective.

RAJAGOPALAN: Behavioralists are the new Baptists, right?

WHITMAN: In a way.

RAJAGOPALAN: I think we’ve got a pretty good sense of the policy arguments in the book. I would really encourage all our listeners to read the book because there’s a whole other academic area that we didn’t get into too much, which is how these problems came about in the first place. This is more debate between neoclassical economists and behavioral economists on what is meant by rationality within standard economic models.

And in the book, both Mario and Glen offer us a whole new theoretical area, which is inclusive rationality, which tries to look at human beings as if they were human—as if they’re not agents in a model, as if they have all these inconsistencies but they still manage to understand the context and the environment that they inhabit and adapt to it and make the best decisions that can be made, even though those decisions don’t always nicely line up in a mathematical model.

So, for that, I would strongly encourage everyone to read the book. Thank you once again, Mario and Glen, for coming on the show. For our listeners, the full title of the book is Escaping Paternalism: Rationality, Behavioral Economics, and Public Policy. It was published in January 2020 by Cambridge University Press, and it’s available on Amazon.

Some of the work done by the Mercatus Center in the area of paternalism, especially some of the policy areas that we talked about—one is in the area of sin taxes. This is an excellent book edited by Adam Hoffer and Todd Nesbit. It’s called For Your Own Good: Taxes, Paternalism, and Fiscal Discrimination in the Twenty-First Century. It takes a lot of the arguments in Taxing Choice, which is an old book by Bill Shughart, and it brings those arguments to the 21st century, where a lot of the fiscal choices are motivated by this kind of new paternalism.

Another area that we discussed is default rules and consumer finance. And in the area of consumer finance, we have a critique of new paternalism by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, by Todd Zywicki and Adam C. Smith. The paper’s called “Behavioral Paternalism and Policy in Evaluating Consumer Financial Protection.” All these will be linked in the show notes. Thank you, again, for being with us. Thank you, Mario. Thank you, Glen.

RIZZO: Thank you. Thank you very much.

WHITMAN: My pleasure, thank you.