The Capitol Insurrection Through the Lens of Chinese Propaganda

China is closely watching the effects of the Jan. 6 riot on America’s democratic institutions

By Weifeng Zhong

When America’s institutions blunder, its competitors and adversaries not only take notice of the situation, they take advantage of it. Indeed, for China, the United States—with its open and at times messy democratic system—offers a target-rich environment. But in the case of the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol, China’s response has been surprisingly measured.

As critics were quick to point out, the Capitol insurrection fed perfectly into the Chinese government’s narrative that democracy doesn’t work and that its authoritarian model functions much better. But due to concerns over its own political and social stability, China has not exploited this narrative for propaganda purposes anywhere near as much as one might expect. At the same time, how American institutions handle the aftermath of the Capitol riot will help determine Chinese perceptions and propaganda going forward. And make no mistake—China is still closely watching how everything unfolds.

What China Is Saying—and Not Saying

A good place to gauge China’s perception of the Capitol riot is its preeminent propaganda outlet: People’s Daily. As the Communist Party’s most authoritative official newspaper—just like the Soviet Union’s Pravda—People’s Daily serves the purpose of shaping public opinion in a way that’s coherent with the government’s policy goals. That’s why important events in the United States, a greater world power that holds very different values, often receive carefully calculated coverage.

The Capitol insurrection is no exception. Perhaps surprisingly, People’s Daily’s coverage of the riot was light, and its attack on America’s democratic system came with a delay. The paper reported on the riot two days after it occurred and on page 16. And the paper waited a full week before offering the view that the event exposed “the hypocrisy of American democracy.”

There’s a reason the Chinese government did not give the insurrection higher-profile coverage: The assault on the Capitol started off as a protest, something the Chinese people are not allowed to do. The rioters stormed the Capitol, thinking without basis that the election was stolen. What if the people in China who question their government’s legitimacy with good reason got the “wrong” idea? As Tyler Cowen recently warned, insurrections can be contagious. And so are legitimate protests, including those that, as we’ve seen in countries around the world, can rapidly lead to a repressive regime’s collapse.

Past evidence suggests that the Chinese government is well aware of the drawback of openly discussing any form of protest or even assembly. Consider the Charlottesville white supremacist riot in 2017. Chinese propaganda’s coverage of the event also was tepid and came with a several-day delay. Moreover, the event made China’s government more alert about potential protests at home, particularly in Xinjiang—home to the country’s persecuted Uighur minority.

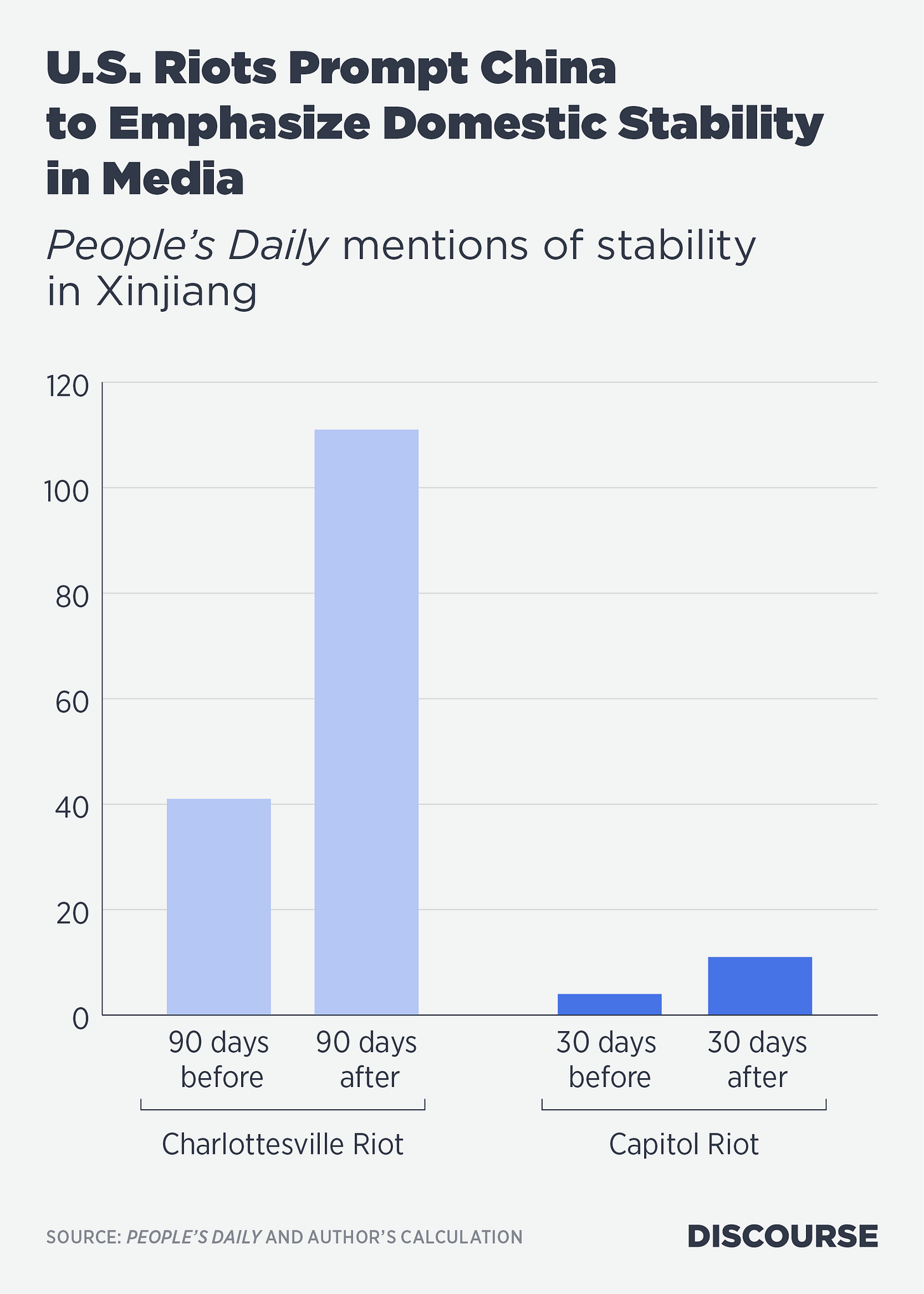

The chart below shows the number of times People’s Daily mentioned keywords related to the stability of Xinjiang during the 90 days before and the 90 days after Charlottesville. The emphasis on the Uighurs, a politically sensitive issue in China, increased from 41 times before the event to 111 times afterward. While it hasn’t been 90 days since the Capitol siege, a comparison based on the 30 days before and after the incident shows a similar pattern.

There’s no justification for the disgraceful attack on the Capitol last month. But the calculated reporting on the event by China’s propaganda suggests that, even on a bad day, America remains a beacon of democracy.

China Is Still Watching

As I have written elsewhere, it is of great interest to the Chinese government whether fair processes, such as those regarding election disputes, are upheld in the United States. If they are not, China will perceive America’s democratic institutions as being weak.

In the case of the Capitol siege, every person engaged in the insurrection should be punished to the fullest extent of the law—no less and no more. So should former President Donald Trump, who appeared to have incited the violence when he urged his mob supporters to “fight like hell.” With that in mind, his impeachment trial in the Senate should move forward as planned.

But punishing these individuals beyond due process would be unjust. Some, for example, have called for the Transportation Security Administration and the FBI to place all Capitol rioters on the no-fly list, before they are even convicted. That is no different from any other illegal pretrial punishment, a practice the Chinese government frequently engages in. For example, Gui Minhai, a Swedish citizen and Hong Kong–based publisher of political gossip books about China’s Communist leaders, vanished while in Thailand in 2015. After what’s believed to be three months of undisclosed custody by the Chinese authorities, Mr. Gui resurfaced with a video confession widely broadcast in Chinese media—all before the suspect was even tried, let alone convicted of anything.

It would also be unjust to punish those who were not involved in the insurrection for the insurrection. Some, for example, have called for expelling from Congress the Republican lawmakers who objected to the Electoral College count, because that, somehow, is believed to have incited the violence. I’m not in any way defending those lawmakers who objected to the result of the election or claimed the election was stolen. They should be punished—by their voters in the next election, not by their colleagues who hold different views.

By contrast, the expulsion of lawmakers from the legislature because of differing views is also a favored tactic used by the Chinese government. For example, Hong Kong used to have pro-democracy lawmakers. Not anymore. Beijing ousted four of them last year—simply because it didn’t like their political views—and the rest resigned en masse in solidarity.

On both sides of the aisle, it is tempting to maximize our own policy preferences at the expense of the liberal order that sets us apart from the unfree world. But one of America’s strongest soft powers in the eye of its rivals like China is its ability to resist that temptation, not to succumb to it. Losing this soft power may well have a larger, longer-term impact than the riot at the Capitol.