The Autodidact's Bookshelf: This Halloween, Don’t Make a Deal With the Devil

Narratives about selling one’s soul raise the perennial philosophical question of fate versus free will

By James Broughel

In a 1993 Halloween episode of “The Simpsons,” the lovable yet short-sighted Homer sells his soul to the devil in exchange for a donut. Fortunately for Homer, Marge remembers he had promised his soul to her years earlier in return for her hand in marriage, thereby making his deal with Satan null and void. The devil, who is a cross between the mythological god Pan and Homer’s Christian neighbor Ned Flanders, is furious but gets the last laugh when he turns Homer’s head into a giant donut at the end of the story.

The “Simpsons” episode was inspired by a 1930s short story, later turned movie, titled “The Devil and Daniel Webster,” in which a farmer down on his luck trades his soul for seven years of good fortune. Eventually, there is a trial over the contract, and the farmer is successfully defended by the famous 19th-century attorney and politician, Daniel Webster.

There is an entire canon of stories within this genre, involving some highly ambitious protagonist in search of a shortcut to fame and success, only later learning the hard way that shortcuts come with significant downsides.

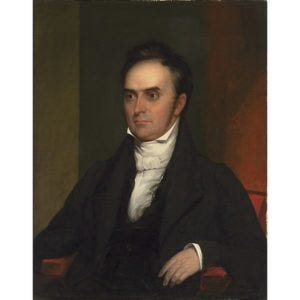

Lawyering up. Portrait of attorney and statesman Daniel Webster. Image Credit: Chester Harding (American, 1792-1866)/Wikimedia Commons

The origins of these stories may in fact be ancient. In the Bible, Jesus spends 40 days and 40 nights fasting in the desert while being tempted by the devil, who promises Christ all the kingdoms of the world if he will only bow down and worship him. There is also an old German folk tale about a mason who asks the devil to help him build a bridge across a river. The devil agrees, but only in exchange for the souls of the first three to cross it. Tricking the devil, the man has a rooster, a hen and a dog go across first.

Modern variants of the story include the classic Roman Polanski film “Rosemary’s Baby,” in which an actor allows a beast to use the womb of his wife, Rosemary, to breed the anti-Christ. In one version from the rock and roll tradition, the blues singer Robert Johnson meets the devil at a crossroads and sells his soul for fantastic guitar-playing abilities. In the 2013 movie “The Devil’s Violinist,” the Italian virtuoso Niccolò Paganini sells his soul for a doting audience and successful concert career. He spends years satisfying his insatiable lust for women and gambling, before the devil’s representative double-crosses him.

The modern incarnations of these “contract with the devil” stories can trace their origins to a late 16th-century play by the English playwright Christopher Marlowe. His “The Tragical History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus” is about a real-life German alchemist, Johann Georg Faust, around whom a mysterious legend grew.

In the play, Faustus grows bored of traditional book learning and takes an interest in dark magic. He summons a demon, Mephistopheles, who is a messenger for Lucifer. For 24 years of fame and fortune, he agrees to sign a contract in his own blood awarding his soul to the devil. Faustus grows rich and famous and embarks on a number of adventures. Along the way, he meets such famed characters as Alexander the Great, and he has a love affair with Helen of Troy. He is offered numerous opportunities to repent, but ultimately, like the violinist Paganini, he opts not to, thereby sealing his fate.

Marlowe’s play served as inspiration for a German version of the same story, written about two centuries later by the poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. His more efficiently titled “Faust” is arguably the greater epic of art and poetry, containing countless literary allusions, especially to the Bible and classical Greek myths. Goethe’s Faust in some ways mirrors the biblical character Job, whose faith in God is put to the ultimate test.

Goethe, like Marlowe, presents Faust as an intellectual who has gone astray. He is talented and brilliant, but has grown tired of the intellectual life, turning to alchemy and magic instead. Faust abandons the books of science and philosophy that represent the path to true knowledge and wisdom, opting for books of spells, astrology and necromancy instead. These might be more exciting, but they are ultimately a spiritual and intellectual dead end. These Faustian narratives teach us that if we aspire to the highest levels of success, we have to put in the hard work, even though some of that work will be tedious and boring.

Part 1 of Goethe’s play centers largely around Faust’s love interest, an innocent young woman named Gretchen whom he ends up impregnating. Realizing Faust cannot be trusted after his actions result in the deaths of family members, she ends up killing her own child and is taken away to jail and sentenced to death. When Faust visits her he tries to get her out, but she resists. In the end, her soul is saved by God because her faith cannot be broken.

In part 2, “Faust” takes a completely different turn, in which Faust is swept away to a pastoral setting, where he embarks upon a series of mythic adventures. Again, Faust engages with such classical characters as Paris and Helen of Troy. Helen and Faust reside together in a utopian land called Arcadia, where she gives birth to a son they name Euphorion.

Temptation. Image Credit: Ary Scheffer (Dutch-French, 1795-1858), "Faust and Mephistopheles"/ Wikimedia Commons

At the end of Goethe’s play, God intervenes and saves Faust’s soul at the last minute, which marks a striking difference from Marlowe’s version of events. For Goethe, women play a central role in guiding men away from their self-destructive natural tendencies. The play ends with the dramatic statement: “Woman eternally shows us the road.”

In the background of all these stories are questions about fate versus free will. Goethe’s play begins with God in heaven praising Faust. It’s as if he knows Faust will not ultimately turn away from him. But if God already knows how the story ends, how can any of us control our own destinies? Some philosophers, such as John Calvin, believed our fates are predetermined, while others see a role for self-determination. Most of these Faustian stories seem to allow for some free will. In Marlowe’s version, dual angels offer the hero competing advice. Faustus can avoid eternal damnation if he repents—he just chooses not to.

Another, more dangerous, lesson is that the devil can temporarily be partnered with—so long as one is cunning enough to outwit him later on. Goethe notes, “Even hell hath its peculiar laws,” which explains how Homer and his counterpart, Jabez Stone in “The Devil and Daniel Webster,” are cleverly able to get out of their seemingly airtight contracts. So too in the German folk tale, the devil must settle for animal souls rather than human ones.

This is a dangerous road to travel, to be sure, and it is one that perhaps America is walking today with its high levels of consumption and debt. Maybe God will swoop in and save us before the bill comes due, just as he did in Goethe’s play. But can we really assume this story has a happy ending?

Homer Simpson somehow manages to avoid an eternity in sprawling landscapes of cherry-red fire. Whether the same can be said for the rest of us will depend on whether we can resist—or outsmart—the everyday evils that continually tempt us. On the other hand, perhaps our fates are sealed no matter what we do.