The Autodidact's Bookshelf: Economists Don’t Have Very Good Answers When It Comes to the Environment

There’s an eternal conflict between civilization and nature—and economists’ efforts to strike a balance between the two usually come up short

By James Broughel

The environment is one of the hottest of the hot button issues that divide the two major American political parties. The Democratic Party’s near obsession with climate change is about as far away from the “drill, baby, drill” philosophy that permeates Republican dogma as one could imagine. Yet these debates about striking the right balance between environmental concerns and economic ones are nothing new. Moreover, economists have shown themselves to be less than fully capable when it comes to settling this most monumental of political disputes.

Striking a Balance

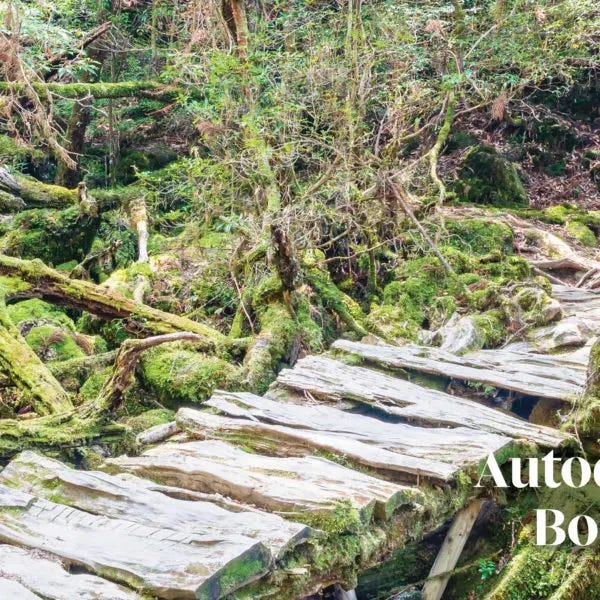

The debates over the balance between the environment and the economy have been with us about as long as there has been human civilization—they’ve even seeped their way into popular culture. One film that captures the essence of these debates is the 1997 Japanese anime movie “Princess Mononoke,” an animated epic fantasy film written and directed by Hayao Miyazaki. The film follows a young man named Ashitaka, who is cursed by a demon and so ventures off on a quest in search of a cure. He becomes embroiled in a struggle between the gods of a forest and the humans living in Iron Town, who consume the forest’s resources. As he tries to find a way to strike a peace between the two sides, he meets Princess Mononoke, a young woman raised by wolves who is determined to protect the forest. Together, they attempt to bridge the divide between the two sides and stop a destructive force that threatens all human civilization.

“Princess Mononoke” explores themes of environmentalism, human progress and the relationship between civilization and nature—and by not portraying either side as completely good or evil, it aptly captures how complicated and nuanced the tension between the environment and economy can be. As an economist who also occasionally writes on environmental issues, I too am interested in the ever-present tension between protecting our planet and creating enough wealth in the market to promote human flourishing and alleviate poverty.

Where Economists Disappoint

Unfortunately, most modern methods used by economists to account for environmental concerns in an economic context come up short for one reason or another. For example, economists have long attempted to price environmental amenities that are not traded in any market using techniques such as “contingent valuation” or “hedonic pricing.” These are fancy terms for surveys and statistical methods that assign dollar figures to things that people care about but aren’t for sale in any marketplace.

As an example, a survey might ask people how much they would be willing to pay to preserve a particular endangered species. Likewise, economists might observe people’s behavior in certain market contexts, such as real estate transactions, and then infer how much they are willing to pay for environmental amenities, such as proximity to nature.

One problem with such approaches is “speciesism,” where resources are valued solely from a human perspective, ignoring any concerns of the animals themselves that might be impacted. While this criticism could be leveled at all market activity—markets, after all, involve trading among people and not animals—even from a purely human perspective attempts to “monetize” nonmarket activity can be problematic.

For one thing, “utility”—the main measure of well-being economists are concerned with—is not a store of value in the same way that money is. So, for instance, comparing a dollar’s worth of enjoyment from watching a beautiful sunrise is not the same as a dollar invested in a savings account (which can result in more than a dollar’s worth of enjoyment in the future).

This misunderstanding creates challenges for economic tools like cost-benefit analysis, as well as “green accounting” schemes that try to incorporate environmental impacts into metrics like GDP. When returns can be reinvested, as is the case with capital traded in markets, society’s base of wealth can grow in a compound fashion. Environmental capital may have lasting benefits too, but the benefits don’t evolve in the same way. Fundamentally, the time profile of returns from natural and physical capital are different.

Also popular among economists are climate models that forecast future impacts of climate change on human well-being. These models assume from the outset a certain functional relationship—called a “social welfare function”—that captures how changes in environmental outcomes translate into changes in human well-being. This built-in assumption requires ethical choices that are usually not transparent and furthermore about which economists have no particular expertise.

Economists do deserve credit for at least taking a stab at these difficult problems in an analytical way, but thus far their efforts have not succeeded. The simple reality may be that it is ethics, not economics, that must guide us as we try to best address our environmental challenges. In this sense, we as a society have probably asked too much of the economists. They may not be able to provide objective answers to questions that are inherently subjective in nature.

A New and Better Future

“Princess Mononoke” ends with a magical forest spirit destroying Iron Town. At first, this appears like a tragedy—human greed and arrogance have brought about a seeming apocalypse—but the tragedy can also be viewed as a new beginning. While the destruction forces people to rebuild, it also raises the prospect that a superior civilization could replace the old one (indeed, the people of Iron Town plan the building of a new and better city), one that is more in balance with nature.

Films like “Princess Mononoke” remind us that man’s pathological pursuit of wealth and power has the potential to destroy both our civilization and our planet. The 2021 film “Don’t Look Up,” starring Leonardo DiCaprio, Jennifer Lawrence and Meryl Streep, offers a similar catastrophic prophecy. The movie draws our attention to the absurdity of the human response to civilization-wide challenges. Too often, rather than confront reality head-on, with all its accompanying inconveniences, we instead opt to maintain a deeply held commitment to the denial of simple and obvious truths.

At the same time, we can’t forget that without the wealth and technology that markets are so good at generating, we can hardly be good stewards of our planet. This creates a role for economists in identifying the most cost-effective solutions once the right questions have been asked. In other words, economics is limited in its ability to tell us what the right questions to be asking are, but it is very good at finding affordable solutions as a follow-up exercise.

As good citizens, we can and should seek to educate ourselves about what values should be elevated in our national discourse. One of those values is certainly protecting the environment. When disputes arise about values, as is inevitable, it is in realm of politics, and not economics, that we must settle our differences.