Tax Expenditures for the Chopping Block: The Child Tax Credit

This costly and badly targeted tax credit falls short in achieving its intended goals, and expanding it would exacerbate its flaws

This is the final article in a series of pieces that focus on individual tax expenditures that policymakers might consider eliminating or reforming to address America’s dire fiscal trajectory. Previous articles in this series have addressed the low-income housing tax credit, tax-exempt interest on municipal bonds, the state and local tax deduction, the earned income tax credit, energy subsidies and college tax credits.

Once the dust settles on the outcome of the 2024 election, the debate over the future of the child tax credit (CTC) is set to intensify. In recent years, this policy—a per-child tax credit offered to taxpayers with dependent children—has evolved into a substantial income-transfer program aimed at reducing child poverty and supporting middle-class families. During the election campaign, both sides, in a tit for tat, called for massively increasing the generosity of this tax expenditure.

And this expenditure is indeed generous already. In terms of fiscal costs, the CTC (absent temporary 2021 reforms) is estimated to cost the government an average of $122 billion annually through 2025. However, proposals to extend 2021 reforms and boost payments for newborns would cost about $1.6 trillion over a decade, according to the Tax Foundation, a nonpartisan nonprofit that researches tax policy. Another nonprofit, the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, estimates that these proposed changes could cost up to $1.9 trillion relative to current law.

Despite the expense, the CTC has bipartisan support. During her presidential campaign, Vice President Kamala Harris proposed not only to restore the enhanced CTC, but to also create a new $6,000 tax credit for newborns. Going even further, Harris proposed to delink the CTC from work by delivering the credit’s full amount to families who pay no taxes and have no earnings. Vice President-elect J.D. Vance has floated a similar bad idea that is certain to redistribute yet more taxpayer funds to high-earning households. But despite support on both sides of the aisle, the evidence suggests that the CTC is badly targeted and poorly suited to achieve its goals. As the father of the CTC, Scott Hodge, noted in a Wall Street Journal article:

I was one of the inventors of the child tax credit, nearly 25 years ago—and I think it’s a bad idea. … [I]t has become one of the largest federal income transfer programs. It is one of the leading reasons that more than 40% of all filers pay no income tax.

Understanding the Child Tax Credit

The CTC was first introduced in 1997 as part of the Taxpayer Relief Act, offering families below a certain income threshold a tax credit of $400 per dependent child. Over the years, the credit has been expanded several times, most notably in 2017 and 2021.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 increased the credit to $2,000 per child and broadened its reach by raising the income phase-out limits. In 2021, the American Rescue Plan temporarily expanded the CTC further, increasing the credit to $3,600 for children under 6 years old and $3,000 for children ages 6-17, while also making the credit fully refundable. This expansion expired the following year.

The refundable portion of the current CTC does not require tax filers to have any federal income tax liability. It begins phasing in at $2,500 of earned income, at a rate of $0.15 per dollar of earned income; a maximum of $1,600 per dependent can be claimed as a refundable credit. The remaining portion of the maximum $2,000 credit must be claimed as a nonrefundable credit that offsets federal income tax liability.

The 2017 and 2021 expansions were lauded by many as a significant step toward reducing child poverty. However, the short-term gain to credit recipients masks deeper issues that make a permanent expansion of the CTC a flawed policy.

A Poorly Targeted Expenditure

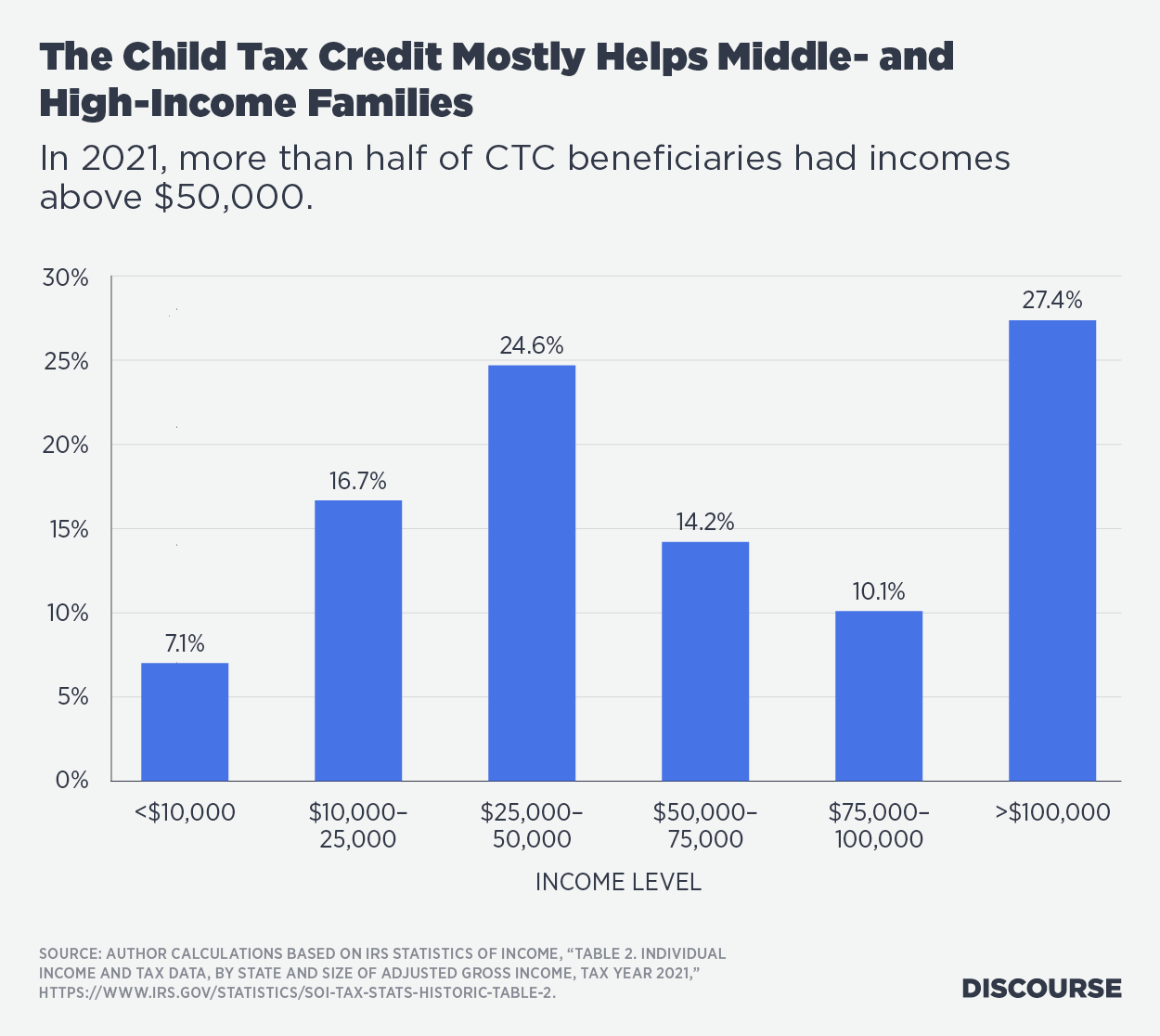

One of the fundamental problems with the CTC is that it operates as a tax expenditure, a type of spending that is often less transparent and less scrutinized than direct government spending. This lack of scrutiny means the CTC is able to effectively function as a subsidy for middle- and upper-income families, many of whom do not need government assistance. This misallocation of resources is evident in the fact that only 19% of CTC expenditures go to the lowest quintile of income earners, who are most in need of financial support.

As the chart below shows, a plurality of claimants in 2021 had income levels above $100,000, while a majority had income levels above $50,000. The data illustrate that, unlike most income-support programs, the CTC is not primarily targeted at low-income families.

The regressive nature of this tax expenditure isn’t limited to the credit as expanded in 2021. In 2019, families earning more than $100,000 claimed 44% of all nonrefundable benefits (at the time, the CTC was not fully refundable), while only 11% of these benefits went to families earning less than $40,000. As Scott Hodge points out in his 2024 book “Taxocracy,” for taxpayers earning between $25,000 and $30,000, the average credit in 2019 was $711, while for taxpayers earning between $200,000 and $500,000, the average credit was $3,018.

Moreover, the CTC’s design creates problematic incentives. By removing the earned income requirement, as was done temporarily in 2021, the CTC can discourage from working the very people it aims to help. Research by economists Kevin Corinth and Bruce Meyer from the University of Chicago suggests that if the temporary removal of the earned income requirement were made permanent, 1.5 million parents would stop working, significantly reducing the policy’s impact on poverty. This decrease in workforce participation is particularly concerning for single mothers, who would be most likely to leave the labor force under a permanent CTC expansion.

The CTC also fails as a tool to increase fertility rates, which are below replacement level in the U.S. Financial incentives like the CTC have been shown to have little impact on long-term fertility decisions. Studies indicate that while financial transfers may lead to a short-term increase in births, they do not significantly affect the total number of children that women have over their lifetimes. This is especially true for the CTC, which primarily benefits middle- and upper-income families rather than the lower-income families that might be more responsive to financial incentives. If policymakers are concerned about declining birth rates, they should focus on addressing the underlying economic and social factors that influence family planning decisions, such as the high cost of housing and child care, rather than relying on financial incentives that have proved to be ineffective.

Reducing Child Poverty?

Since the passing of the American Rescue Plan in 2021, which significantly expanded the CTC, economists have argued that a permanently expanded CTC “would dramatically reduce childhood poverty.” Indeed, measures of child poverty did observe a 29% reduction with the expanded allowance (from 17% to 12.1%).

However, accounting for the 1.5 million parents expected to stop working if the CTC were permanently extended (according to the Corinth and Meyer study), this reduction in poverty lessens to 22%. While still a relatively impressive figure, it doesn’t account for other unintended consequences of permanently expanding the CTC. Some parents would likely work fewer hours, while others might choose not to marry or to divorce in order to maximize their financial benefits. As Scott Winship noted in The New York Times, for families with the weakest attachment to stable work and family life, “it would be likely to consign them to more entrenched multigenerational poverty by further disconnecting them from those institutions.”

A Better Path Forward

Rather than expanding the CTC, Congress should focus on policies that reduce the cost of living for families with children. These policies could include deregulating housing markets to make it easier for families to afford a home, reforming child care regulations to increase supply and reduce costs, and improving access to educational opportunities through school choice initiatives. Intermediate reforms could simplify and consolidate existing benefits without adding new or larger subsidies to the existing system.

Additionally, rather than allocating almost $2 trillion to expanding this tax expenditure, policymakers could use that money to lower tax rates for low-income families. The focus should be on simplifying the tax code, reducing the administrative burden on families and the IRS, and promoting economic growth by allowing families to keep more of their earnings.

Although economists and policymakers continue to debate the CTC’s impact on reducing short-term poverty, its expansion is not the right solution for the long-term challenges facing American families. The CTC is poorly targeted, creates perverse incentives, promotes labor force detachment, and is unlikely to achieve its intended goals of reducing poverty or increasing fertility rates.