Tax Expenditures for the Chopping Block: The Earned Income Tax Credit

The EITC doesn’t alleviate poverty or help the people it’s trying to help—and it’s rife with fraud and abuse

This article is part of an ongoing series of pieces that focus on individual tax expenditures that policymakers might consider eliminating or reforming to address America’s dire fiscal trajectory. Previous articles in this series have addressed the low-income housing tax credit, tax-exempt interest on municipal bonds and the state and local tax deduction.

After a series of new welfare programs was launched in the 1960s as part of Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society legislation, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) was introduced in the 1975 Tax Reduction Act as a temporary program aimed at incentivizing work. The EITC is a refundable tax credit for low- to moderate-income individuals and couples that directly reduces the amount of tax they owe on a dollar-for-dollar basis. It is meant to encourage lower-income Americans to join the labor force.

As with most “temporary” government programs, the EITC was eventually made permanent in 1978. Its initial scope was relatively limited—a credit of up to 10% of eligible workers’ earned income, capped at $400 and available only to working adults with children. The subsidy has since been expanded multiple times through various tax reform packages, which have increased both eligibility and maximum credit payments.

For example, in tax year 2023, a single filer with no children could qualify with an income up to $17,640, while a married couple filing jointly with three or more children could qualify with an income up to $63,698. The maximum credit ranges from $600 for filers with no children to $7,430 for those with three or more children. To claim the EITC, filers must have earned income from employment or self-employment and meet specific rules related to filing status and residency.

The tax credit begins to phase out for a single filer with one child at an income of $21,560 and is fully phased out at $46,560; for a married couple filing jointly with three or more children, it starts phasing out at $28,120 and phases out completely at $63,398.

In terms of fiscal costs, the EITC is estimated to cost the government an average of $76 billion annually. The Treasury estimates that over the coming decade (2024-2033), the total cost of this tax credit will be $759 billion. But the so-called benefits of the EITC don’t outweigh these costs, and the credit is also uniquely susceptible to fraud and error. Policymakers therefore should consider eliminating this credit to improve America’s fiscal trajectory.

Not a Great Anti-Poverty Program

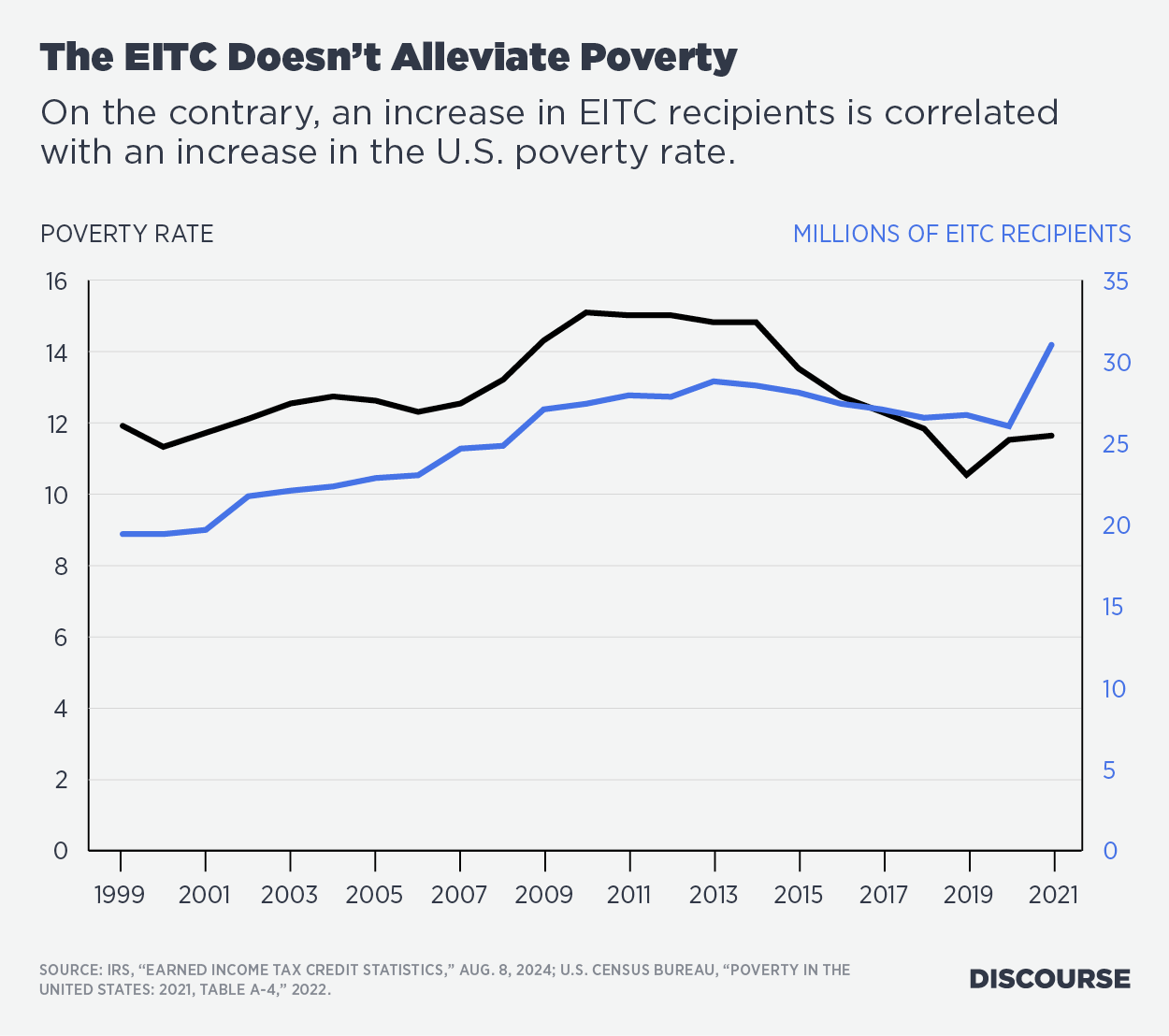

A major purpose of the EITC is to reduce poverty by incentivizing recipients to join or rejoin the labor force. But while the number of EITC recipients grew by a staggering 49% between 2000 and 2013, the poverty rate during this period also grew by about 3.5 percentage points. Similarly, as the chart below demonstrates, the number of EITC recipients declined between 2013 and 2020, and the poverty rate also fell during this period.

In 1975, 7.5% of earners claimed the EITC, but by 2020 the proportion had doubled to almost 16% of earners. In 2021, the Biden administration temporarily expanded the credit to taxpayers with no qualifying children and expanded the age range for eligible workers—which led to more than 1 in 5 workers claiming the credit in 2021.

Although more and more people are claiming the EITC, it indirectly harms those low-income workers who are ineligible for the subsidy, particularly low-income childless workers. If successful in inducing work, the EITC would increase the supply of labor in the marketplace. An increase in the supply of low-income workers would, in turn, reduce the market rate of wages. Research focused on the effects of the EITC on ineligible workers finds that $0.36 of every EITC dollar ends up in the pockets of low-skilled workers’ employers because of reduced wages. The same study finds that the welfare of EITC-ineligible childless women (meaning the overall well-being of these individuals, including income, consumption of goods and services, and amount of leisure time) falls by $0.18 on every dollar earned.

Impact on Work Incentives and Families

In addition to harming low-income workers, the EITC also has deleterious effects on other groups of people. One of the largest expansions of the EITC occurred in the early 1990s: Tax reforms increased total EITC enrollment by about 52% between 1990 and 1994. Employment of single mothers also rose during this timeframe, which has been claimed as evidence of the EITC’s success. But while some economists have argued that the expansion of the EITC could explain about a third of the rise in employment among single mothers in the 1990s, others have argued that this observation is empirically fragile because the 1990s tax reforms also coincided with welfare reform and robust economic growth.

In fact, during the early 1990s, labor force participation among single mothers increased only modestly. About 70% of the increase in participation among single mothers occurred between 1994 and 2000—a period when EITC enrollment saw a measly 1% increase.

Another concern is the EITC’s effect on second earners in married households. Research has shown that the EITC discourages labor force participation among secondary earners with low-income spouses. One study found that the EITC reduced the participation of women with husbands earning below $24,000 by roughly 10%-12% in the 1990s when the program was expanded.

Other research has found that EITC expansions between 1984 and 1996 led to modest reductions in hours worked by married men and married women, while women in the phase-out range of the credit experienced the greatest reductions, between 3% and 17%. This suggests that economists should consider the impacts of the EITC not only on labor force participation, but also on changes in hours worked by targeted and nontargeted groups.

Another 2018 study found that some eligible women can expect to lose about half of their pre-marriage EITC benefits following marriage, making them 2.5 percentage points less likely to marry their partner than single mothers who expect no change in their benefits. At a time when 40% of births are to unmarried women, we should be wary of subsidy programs that further discourage marriage.

A Serious Fraud and Error Problem

Not only is the program ineffective at achieving its goals, but many of the recipients of the EITC make fraudulent claims to receive the tax credit. Combined with poor administration, this results in billions of dollars in mispayments and overpayments every single year. The IRS estimates that an astounding 33% of EITC claims are paid in error every year—that’s roughly $25 billion a year in lost revenue due to error and fraud alone.

A compliance report conducted by the IRS found that the overclaim percentages for the EITC were between 29% and 39% during the period 2006-2008 and between 31% and 36% in an earlier study looking at older tax data. Among taxpayers who overclaim the EITC, around 80% turn out to be ineligible for the credit altogether, rather than eligible for a smaller credit amount.

This problem hasn’t improved over time. In 2023 the Treasury inspector general published a report focused on tax year 2022. The report found that the improper payment rate for the EITC was 32%, up from 28% in 2021.

In Desperate Need of Reform

The EITC modestly boosts workforce participation but comes at a significant fiscal cost. Despite its intention of reducing poverty, the EITC has seen substantial growth in recipients without corresponding decreases in poverty rates. And this growth did not significantly affect labor force participation among targeted groups, such as single mothers in the 1990s.

Furthermore, the EITC creates negative side effects, including reducing wages for ineligible low-income workers and discouraging labor force participation among secondary earners in low-income households. The program also suffers from significant fraud and mismanagement, with about a third of claims being erroneous, leading to billions in overpayments annually. At the very least, policymakers should aim to cut out the waste and fraud that is such a prominent feature of the EITC program.

Rather than attempting to subsidize labor force participation, policymakers should focus instead on policies that boost wages and employment and reduce barriers to entering the labor market. Removing or eliminating burdensome occupational licensing requirements that affect low-income workers and pursuing tax reforms that lower the burden on businesses and workers—all of which would encourage investment, business expansion and job creation—would be a good place to start.

If policymakers want to make the EITC more effective at increasing labor force participation, there are reform options available. The program, as currently structured, has no working hour threshold. Establishing a 30-hour threshold for benefits might encourage non-working individuals to work, rather than paying those already working to keep working. As NYU Professor Lawrence Mead notes:

The idea that “making work pay” can by itself raise work levels significantly has obvious appeal. It suggests that, if society just gives poor adults a better deal, they will choose to work on their own, without the unpleasantness of work enforcement. Experience shows, however, that this kind of incentive is very unlikely to suffice.