Systems and Constraints

Martin Gurri talks with Alicia Juarrero about her theories of stability and change in the context of government institutions

By Martin Gurri

This interview is a companion to an article about Alicia Juarrero’s ideas that is also published on Discourse.

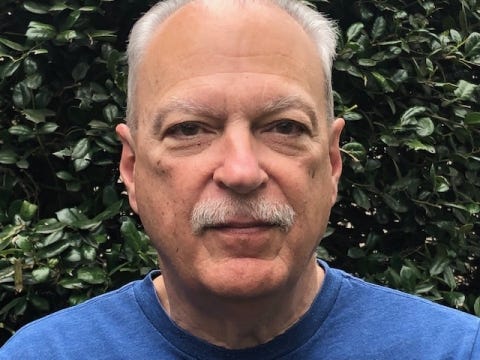

Alicia Juarrero is the founder and president of Vector Analytica, Inc., a software development firm in Washington, DC. Her books include Dynamics in Action: Intentional Behavior as a Complex System (1999) and the forthcoming Complexity and Constraint: How Context Changes Everything; many of her papers can be found at her website, www.aliciajuarrero.org. Juarrero has taught philosophy at Prince George’s Community College in Maryland and has been a visiting scholar at Georgetown University in Washington, DC, and Durham University in the United Kingdom. She received her BA, MA, and PhD from the University of Miami in Coral Gables, Florida.

Recently, Juarrero spoke with Martin Gurri, a visiting research fellow at the Mercatus Center. This transcript of their conversation has been slightly edited for clarity.

MARTIN GURRI: In your terminology, institutions could be described as strange attractors that constrain system behavior toward specific outcomes. If we take modern government as our example, would you say these institutional constraints are inherently stable or unstable? What determines stability or instability within a system?

ALICIA JUARRERO: Complex systems such as institutions are hierarchically entangled networks—entangled across spatial and temporal scales. Networks are nested within networks that are in turn nested within more encompassing ones. I think it’s important to use the term system for the totality: both the individual and smaller actors and the larger and more persistent dynamics (attractors) in which these are caught up.

I think of the stability of a system within a larger institution more as a question of the degree of coherence or fit between the two. Fit in the sense of fittingness, not in the sense of old-time Darwinian interpretation of fastest or most efficient, etc. You never want a perfectly fit, coherent, and therefore stable system (therein lies stasis and death). But for a system to evolve and thereby persist over time requires a certain (unspecified!) resilience more so than stability. I do think that the world finds itself at a moment in history where, for a variety of reasons that have come together simultaneously, the fit between the two is very strained.

GURRI: A case can be made (I have done so at length) that the institutions we have inherited from the 20th century have lapsed into in a state of terminal crisis: they are in the throes of what you would call phase change. Sticking with modern government as our example, what elements would you look for in a system to determine the outcome of the transformation? Can post–phase change outcomes (government in transition, in our example) be predicted in any way?

JUARRERO: We cannot know ahead of time if it’s terminal because we cannot predict complex systems in detail, except in the very short term, and even then, only when they are in a stable state. You cannot predict because they are nonlinear, sensitive to initial conditions and context in general, etc.

Three options are possible once a complex system reaches a threshold of instability: adaptation, evolution, or disintegration. There is never a guarantee that the whole will not collapse, which it will do if we are unable to adapt and evolve to achieve a new coherence or fit. I think of adaptation as modifications within a given space of possibilities. You either expand your adaptive capacity or move to a more stable location within that adaptive space.

So if we jury-rig capacity such that it can handle the currently higher amplitude and frequency in the perturbations, we’ve adapted. For example, the suggestion that there be a national stockpile of health emergency equipment like the petroleum reserve is an example of expanding adaptive capacity. Ongoing epidemiological surveillance such as that proposed by the Stockholm Paradigm would be another.

I envision evolution, on the other hand, as a comprehensive reconfiguration of the entire space of possibilities such that it becomes structured with entirely new actors (roles) and patterns. Some argue that on that criterion the French Revolution was a real revolution, but not the American Revolution. In nature, such a reconfiguration is easier to spot. The evolution of vertebrates, the emergence of language, the development of agriculture, and the Industrial Revolution would be four examples.

Radically new technology has the capacity to affect that kind of full-blown phase change. But so does the closure of a new set of interdependencies. Working that out is at a very incipient phase, though, especially with respect to social systems.

GURRI: To what extent is it possible to control, or at least influence, the outcome of phase change once it has begun? Is there a way to reshape or reform a system such as modern government from within? In this endeavor, would an authoritarian government (for example, China’s) hold an advantage over a noisier and messier democracy?

JUARRERO: The direction and speed a phase change will take are influenced by whether or not any novel fluctuation appears and is amplified by the current environment such that it becomes the nucleation for the phase change itself. We do not know enough about how to detect and manage the timing of such fluctuations.

I think authoritarian governments can clamp down and thus enforce the constraints that held the status quo together—but I know of no cases where new coherences evolve from top-down, much less strong-arm, tactics. I suspect that clamping down longer than necessary results in a much more drastic phase change than if change is allowed to happen earlier. I would place my long-term bet on India rather than China—and of course, I think no country on earth beats the American capacity for change.

But evolutionary upheavals are not pretty or pleasant. Alas, creative destruction destroys a lot in the process. We can look to ways to making it easier for those negatively affected without trying to prevent the transition.

GURRI: Singularities, you have said, are unique events that trigger phase change. At what point is it possible to recognize an event as a singularity? What does the pandemic crisis look like to you from this perspective?

JUARRERO: As I see it, a singularity is unique and can trigger phase change . . . but only under such and such circumstances. Under other circumstances those same events might not be that influential. We forget the importance of temporal constraints—timing—in complex systems. Since we can only catalyze and not command phase changes, identifying and taking action during temporal windows of change—which might close if not taken advantage of—is a very interesting area of study that hasn’t been explored much.

I do think one management technique that might be useful would be to identify small experiments in the direction we want to see change occur and amplify those by providing resources to allow them to flourish. The United States’ federal organization effectively institutionalizes that possibility. A different way of doing the same thing is to loosen governing constraints that hinder the amplification of new ideas. Again, bottom-up fluctuations are more likely to succeed than top-down ones. But top-down constraints that are too rigid will prevent innovations coming from the local level from bubbling up.

As a complex system decompensates, the wild fluctuations and oscillations that occur—and happen more often and with greater amplitude than is characteristic of the system—often precede a phase change. Complete disintegration of the constraints governing the overall system (as in the meteor strike that destroyed the dinosaurs and perhaps precipitated the Cambrian explosion, or as in the fall of Rome) can also precipitate a phase change. But complex systems ordinarily degrade gracefully—they go through a period of decompensation; they are dysfunctional but not yet nonfunctional—before total collapse.

To judge if this pandemic constitutes a singularity that will lead to a phase change would require a much wider lens than anyone possesses.

GURRI: You describe a kind of dance between the local and the systemic. A local event can sometimes rise to have a global impact: the “shot heard round the world.” Can you comment on this from the perspective of the protests which followed the killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis policeman? When (and how) can we be sure that the impact is permanent, and not an artifact of the moment?

JUARRERO: Kant described that dance way better than I ever could. Trees, he said, are produced by the leaves and in turn produce the leaves—parts interact to produce a novel whole, which in turn loops back down to produce the parts. This parts-to-whole and whole-to-parts influencing, he said, “is unlike any kind of causality known to us.” And indeed, to this day, we still don’t quite understand recursive causality among parts and wholes—certainly not in human organizations.

Again, timing is one constraint that plays a role in these dynamics, and one we don’t understand very well in human organization. We do in some dynamics: think of a child’s swing. It isn’t so much how hard the child kicks to make the swing go higher; it’s when the child performs the kick that matters. So context-dependence is central to whether or not an event can have a global impact.

The George Floyd killing took place under uncommon circumstances: after weeks of a pandemic-caused lockdown; with Trump, not Obama, in the White House; at a time when everyone has cell phones with cameras. But phase changes of complex systems can be understood only in retrospect; they cannot be predicted in detail the way the precise second an eclipse will occur centuries hence can. We Americans love the idea of “This time is different,” but we won’t be able to tell except in retrospect.

GURRI: Finally, how did you become interested in this esoteric subject?

JUARRERO: My dissertation was about “Explanation and Justification of Moral Behavior.” Explaining behavior involves spelling out why something happened. In the case of blinks, the explanation is straightforwardly mechanical causes: dust blown into my eyes caused me to blink. Explanation of winks, on the other hand, doesn’t yield straightforwardly to that kind of cause—the explanation is more along the lines of “My intention to wink caused me to. . . .” Same for “I raise my arm” versus “My arm rises.” The latter can be explained in terms of a spastic twitch, the insertion of an electrode, etc. “I raise my arm,” on the other hand, implies intentionality.

So how does intention cause behavior? That is what I’ve been interested in since the dissertation.