Sizing Up Pandemic Relief for Business

The Small Business Administration’s loan programs have been plagued by inefficiency, fraud and other stumbles, but the next package may be on its way

By Tad DeHaven

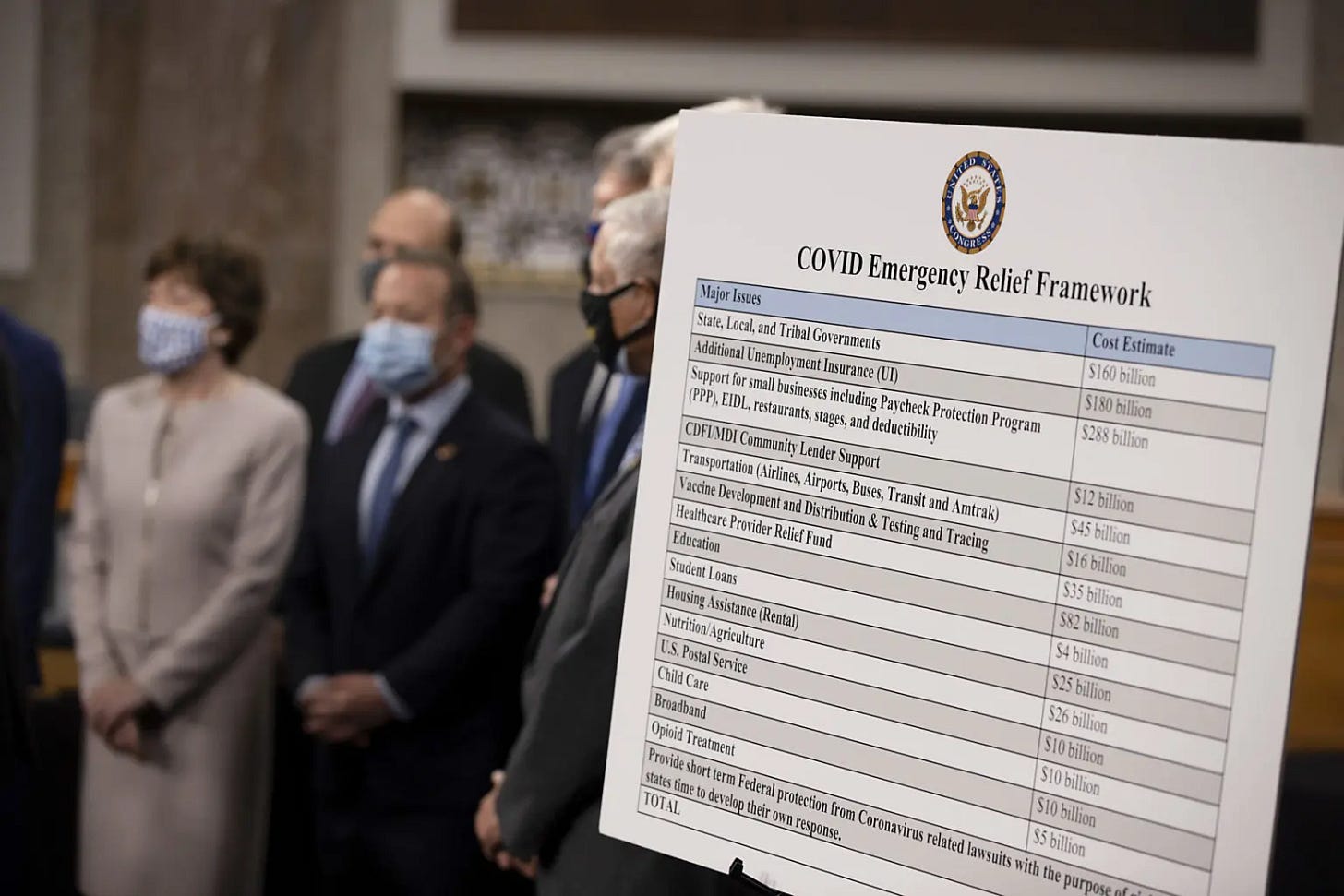

Regulations, government-imposed lockdowns and customers’ fear of contracting COVID-19 have led to an estimated 100,000 permanent business closures across the country, with tens of thousands more on the brink. Federal policymakers responded to the outbreak in March by rushing out legislation that included having the Small Business Administration quickly facilitate emergency low-interest, forgivable loans to small businesses and nonprofits. The effort has received a steady stream of negative press, but Washington may soon replenish the funding to the tune of $300 billion as soon as this week.

To be fair, the question of how policymakers should respond to this epochal pandemic is complicated and polarizing in the extreme. And small businesses still face the prospect of more state-imposed restrictions and reduced foot traffic until we have a successful vaccination effort. Even if there were no alternative to tapping the federal government’s vast borrowing power to keep hundreds of thousands of businesses afloat, the results so far show that outside-the-box thinking is needed.

The Trump administration and Congress concocted the SBA’s Paycheck Protection Program, or PPP, to help small outfits maintain their pre-pandemic payrolls by guaranteeing loans issued by private lenders that would be forgiven if the recipient met certain conditions. After an initial $349 billion for loans was swiftly exhausted, Congress authorized another $310 billion. When applications were cut off in early August, a total of 5.2 million loans worth $525 billion had been approved. In addition, the SBA has signed off on almost $200 billion in nonforgivable loans under the Economic Injury Disaster Loan program, which is still accepting applications, and another $20 billion in Advance grants under the disaster loan program, which are no longer available.

Flaws in the Paycheck Protection Program

In designing the PPP, policymakers faced conflicting concerns: too much red tape and the money may not reach its intended targets in time or at all; too little and the program’s effectiveness would be undermined by waste and fraud. The result was a clunky rollout that saw larger companies with established banking relationships move to the head of the line while smaller, less-connected businesses waited in the back. That was followed by months of reports of dubious recipients and fraudsters.

Take, for example, a Bloomberg report from October on widespread fraud with the Advance grants:

For a few months this year, a U.S. government aid program meant for struggling small-busines owners was handing out $10,000 to just about anyone who asked. All it took was a five-minute online application. You just had to say you owned a business with at least 10 employers, and the grant usually arrived within a few days.

People caught on fast. In some neighborhoods in Chicago and Miami, it seemed like everyone made a bogus application to the Small Business Administration’s Covid-19 Economic Injury Disaster loan program. Professional thieves from Russia to Nigeria cashed in. Low-level employees at the agency watched helplessly as misspent money flew out the door.

Even after the $20 billion in funding for grants dried up in July, the fraud continued, as scammers looted a separate $192 billion pot of money set aside for loans “I’ve never seen anything like it,” said an SBA customer-service representative who spoke on the condition of anonymity to protect her job. “I don’t think they had any processes in place. They just sent the money out.”

As the article later notes, the cost of the fraud meant that legitimate businesses were left out. And according to a report last month, SBA loan officers are claiming that the agency’s management is instructing them to avoid using the word “fraud” in writing if they spot suspicious applications. “Two people said managers cited concerns that loan officers’ notes could be subject to the Freedom of Information Act,” the story noted. “Another person said a manager explained that the word ‘fraud’ was banned because it could eventually become public through lawsuits.”

The Wall Street Journal reported last month that “several hundred PPP-related investigations have been opened, involving nearly 500 suspects and hundreds of millions of dollars of loans, according to the FBI.” Like ants and flies at a picnic, fraud and abuse are natural byproducts of government spending programs, although a former Justice Department prosecutor quoted by the Journal says that in this case, “The scandal is what’s legal, not what’s illegal.”

Studies of Effectiveness

While there have been some preliminary studies on the effectiveness of the relief programs, until this month the SBA had released data only for loans of $150,000 or more, which account for less than 15% of all recipients. A federal judge ruled, however, that the SBA must release information on all recipients by Dec. 1, and the administration reluctantly acquiesced.

Early analysis of the complete data reinforces what was already known: much of the money went to larger businesses, and some went to business tenants at properties owned by the Trump Organization and the president’s son-in-law and senior adviser, Jared Kushner. The former is an unsurprising outcome of the programs’ design and the intense lobbying from industries angling for exceptions. The latter appears to be a case of guilt by association because there seems to be no evidence that either Trump or Kushner used his power to move those businesses to the front of the line.

The issue of undeserving, unsavory or politically connected entities receiving SBA pandemic assistance is not as cut and dried as it seems. As my colleague Matt Mitchell and I discussed in a piece for Business Insider in August, neutrality regarding eligibility is preferable to policymakers attempting (futilely) to decide which companies are deserving of assistance and which are not. While some people may not be happy that federal relief money benefited businesses connected to President Trump or, for example, affiliates of Planned Parenthood, having political actors determine winners and losers invites a whole host of additional problems. If the federal government is going to help businesses that are struggling through no fault of their own, then it should do so in a neutral, nondiscriminatory fashion.

Shortly after the PPP was created, my colleague Veronique de Rugy and economist Arnold Kling proposed an alternative: have the federal government back a line of credit that would be offered to all businesses with a checking account. In contrast to the inefficient SBA-led effort, this would have been simpler, offering generous borrowing terms while maintaining an incentive for only the truly needy to apply. It would have also removed the ability of policymakers to discriminate for or against particular businesses and industries. Alas, de Rugy and Kling acknowledged that their “cure won’t work if the economy is kept in a coma for months,” and noted that “in reality there exist no good solutions for very long shutdowns.”

Alternative Relief Solutions

The next relief package is being negotiated, and presumably policymakers will tinker with the terms and conditions in light of the criticism of the original program. That will generate debate, but that debate likely won’t include much talk of a decentralized approach. No matter what you think of the shutdowns and lockdowns, certainly the case can be made that federal taxpayers (current and future) should not pay for decisions made by state and local officials to curb economic activity. For one, it creates an incentive for officials to ignore the cost of the restrictions. And cutting off federal assistance would give state policymakers a greater incentive to confront pre-pandemic regulations that are hindering both business formation and the financial health of established outfits.

Bankruptcy is an option for struggling business owners, although the uncertainty over when commercial activity will fully resume has led some to simply close rather than go through the restructuring process. Fortunately, a 2019 law called the Small Business Reorganization Act made it less onerous and costly for a small business to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. While the law limited this option to businesses with up to $2.7 million in debt, the CARES Act helpfully increased that amount temporarily to $7.5 million.

If there is a silver lining to this situation, it is the large number of resilient individuals finding their entrepreneurial spirit and meeting the challenges head on. And as another recent piece in the Wall Street Journal shows, these budding entrepreneurs are coming from all walks of life:

To adapt to the pandemic and the job loss it unleashed, more Americans are becoming their own bosses, setting up tiny businesses to work as traveling hair stylists, in-home personal trainers, boutique mask designers and chefs. A man in Maryland started a mobile car-washing business.

Many new entrepreneurs previously worked at salons, gyms and restaurants, in the kind of face-to-face jobs erased when state orders closed swaths of the economy in the spring. The economy has since mounted a split recovery, with some Americans thriving while many others continue to struggle. A cohort of the laid-off, stuck on the descending arm of that recovery, are using their ingenuity to get off it.

Indeed, while thousands of businesses have shut their doors for good, federal statistics also show a major increase in new businesses. Policymakers could boost this trend by removing obstacles to business formation, with occupational licensing regulations being at the top of the list.

The SBA was handed a mission impossible and the results were predictable. The relief efforts helped many businesses remain viable, but at a huge cost. The story still has a long way to go. In the meantime, let’s hope that a successful vaccine, constructive policy reforms and “rugged entrepreneurship” steer the economy to a much better place come spring.