Separating the Man From the Monster

A lot of great artists are horrible people. Should we think less of their art as a result?

By James Broughel

Hollywood has always had its share of wholesome movie stars. 1950s celebrities such as Fred Astaire or Jimmy Stewart are classic examples of lead actors with a squeaky-clean image. Their modern-day counterparts might include stars such as Tom Hanks or Julia Roberts, whose good behavior has come to define them almost as much as their movies.

But these often aren’t the public figures whom, deep down, we most wish we could emulate. They aren’t considered “legends” to the same extent as, say, Marlon Brando or Marilyn Monroe, who are idolized as much for their personal failings as for their on-screen performances. Their dual natures, alternating between heroic and severely flawed, made them more like real people we can all relate to.

Some of those “keeping it real,” however, have shortcomings that go too far. Sometimes artists’ moral failings are so great that they make us uneasy about whether we ever should have liked their art in the first place. It’s hard to imagine someone who had a cleaner image than Bill Cosby—that is, before he went to prison for sexual assault. Then there’s R. Kelly, who had a spiritually uplifting public image but was secretly abusing young girls in his private life.

From Woody Allen to Michael Jackson, there is a long list of such Jekyll and Hydes in our public discourse, people who are spectacularly talented but also make spectacularly bad personal decisions. Often they get away with their bad behavior for a time because they are in positions of authority or are viewed as eccentric geniuses. Eventually, however, the monstrous behavior catches up with them, at which point we inevitably ask ourselves: Should we think less of their art as a result?

One celebrity who paid very little legal or professional price for his ethical lapses was Roman Polanski. He was convicted of statutory rape of a 13-year-old girl and also gave her alcohol and sedatives, but he fled the United States and so never served his time. Many in Hollywood and among his fans seem willing to give the man a pass, not because they necessarily find his behavior acceptable but because films such as “Chinatown” and “Rosemary’s Baby” are considered modern-day classics. Even his own victim eventually forgave him, though some still claim his art should be downgraded regardless.

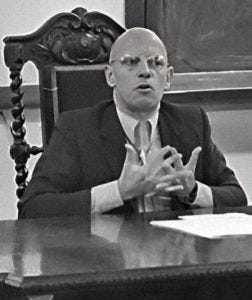

Philosopher, alleged pedophile. Michel Foucault in 1974. Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The French philosopher and historian Michel Foucault demonstrates that it’s not always possible to completely separate the art from the person creating it. He was accused of sex with underage boys while he lived in Tunisia in the 1960s. To be fair, the truth of the accusations is still debated, but if they are true, they could help explain some of his philosophical positions. Foucault argued that underage children could give sexual consent, and his overall conception of liberty questioned authority and sought to tear down societal norms and structures.

Changing beliefs about morality also change perceptions about artists’ work. One famous example is the Marquis de Sade, from whom we get the terms “sadist” and “sadomasochist.” He wrote “The 120 Days of Sodom,” a highly explicit tale of four wealthy libertines who lock themselves in a castle and engage in depraved and sometimes violent sexual acts. His personal activities were considered so outlandish during his lifetime that he spent more than 30 years in prisons and mental facilities for sodomy and various obscene activities. His most famous book has been banned by numerous governments in the past. Today, however, his writings are read alongside classic works of literature.

Writer, sadist. The Marquis de Sade. Image Credit: Charles-Amédée-Philippe van Loo/Wikimedia Commons

This example highlights that sometimes what makes someone scandalous to one generation can make them cool to the next. The reverse is also true. Marilyn Manson was always a controversial figure, but people seemed to take his BDSM lifestyle with a grain of salt in the 1990s. In the #MeToo era, the same activities led to him being canceled. Or consider Dustin Hoffman, who was once viewed as a huge flirt but later came to be thought of as a sexual harasser.

Perhaps the dividing line between acceptable and unacceptable sexual behavior should be whether someone is using other people as mere objects of pleasure, or instead whether others are being respected as autonomous human beings. This is why, for example, Jeffrey Epstein’s behavior was so troubling. He treated young girls as mere playthings for the rich and powerful, not people in their own right.

Notably, the vast majority of such behavior comes from men rather than women. Sure, female celebrities such as Martha Stewart and Winona Ryder, convicted of insider trading and shoplifting respectively, can also demonstrate some pretty significant character flaws. But Stewart and Ryder did not commit crimes one usually considers to be deeply morally problematic. Perhaps that’s because sexual deviancy is especially disreputable in our culture, and that appears to be a mostly male phenomenon, at least by the currently fashionable standards of morality.

Given shifting moral sands, we never know exactly how our actions will be judged in the future. Some, like those who supported gay marriage early on, come to be viewed as ahead of their time. Others, such as Charlie Sheen, come to be viewed as scoundrels, despite their behavior being mostly tolerated in an earlier time.

Because of these evolving beliefs about what constitutes good character, it is probably a mistake to judge art by its creator. Understanding a creator can sometimes help us better understand the art, but the quality of the art doesn’t somehow rest upon its creator being a good person. Indeed, it is often because of the conflicted nature of a person that great art gets made. That doesn’t mean that we need to accept the behavior of the Michael Jacksons of the world. But it does mean we shouldn’t feel guilty when we sing along to “Beat It.”