Rebel Rebel

Throughout his career, David Bowie collected and wore many different identities. Long before the internet and social media, he was creating art by assembling and interpreting his experiences

Let me begin with a confession: Before David Bowie died, I scarcely knew who he was. I’d listened to the classics: “Heroes,” “Let’s Dance,” “Space Oddity.” I had a faint idea of a character called Ziggy Stardust who wore tight, colorful pants. But when a friend visited me in London in 2016 and asked if I wanted to go see “Lazarus,” a musical Bowie had completed just months before dying of liver cancer in his New York City apartment, I was indifferent.

We didn’t end up going to watch the production, but we did go to a viewing of Bowie’s personal art collection. And from what I can remember, I enjoyed it well enough. But in the course of writing this piece, I went back to look at that same day in my calendar and saw that I had accidentally written the event down as “Bob Dylan Art Collection.” (I’ve since been told that I’m not the only person to get the two of them confused.)

Bowie as Ziggy in 1972. Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Today, my relationship to David Bowie couldn’t be more different. I am completely and utterly obsessed, not only with his music—although he did come in first place on my “Spotify Wrapped” this year—but with the man himself. I have watched every interview available on the internet, seen almost every movie he acted in and read plenty of books about him. My friends even tell me I dress like Bowie. I cannot, to their disappointment and mine, sing like him.

Knowing what I know about him now, I think it’s quite fitting that my first encounter with Bowie was with his art collection. Bowie was a collector in the truest sense of the word. He collected art (from Italian Renaissance master Jacopo Tintoretto to Yoruba sculptor Romuald Hazoumè), he collected books, he collected ideas, he collected identities—and he wore them all like T-shirts. He was perfectly aware of this tendency—he routinely called himself “a collector”—and he said that this all amounted to a sort of “hotchpotch philosophy” toward life.

I’ve come to think that Bowie’s hotchpotch philosophy has plenty to contribute to the liberalism that is currently being proselytized by most liberals. It was at once comedic, confident and supremely sexy—anarchically anti-essentialist and deliciously subversive. And at a time when liberalism is increasingly equated with thin skins and self-absorbed elitism on the one side, and loneliness and social fracture on the other, I think progressives could do worse than pay attention to Bowie now.

Ch-Ch-Ch-Ch-Changes

As I write these words, I am at my desk watching David Bowie—a David Bowie who is clearly high on cocaine—fidget with a black cane while fluttering his eyelids, bright orange hair in a skinny dark suit. He’s on “The Dick Cavett Show,” the year is 1974, and Cavett is letting Bowie know just how many people have told him they’d be scared at the prospect of sitting down with him. Bowie giggles but doesn’t seem to take any offense. “That’s what you want, really, isn’t it?”

He then asks the cream-blazoned, floppy-haired Cavett to offer his opinion: “What do you think I’m like?” he inquires, coyly. Cavett tells him he thinks he is an actor who is forever playing a different role: “I hope this doesn’t insult you!” he says.

Bowie is far from insulted. “That’s right. That’s very good.” He touches his tongue and bites his lip, then chuckles, shuffles his feet and peers down at his cane. The whole scene is magnetic. He looks wildly guilty and wonderfully innocent. It’s as though he’s toying with everyone in the room, including himself.

Cavett was right: When you were talking to Bowie, you never really knew whom you were talking to. Bowie took the age-old advice about wearing layers to keep warm and applied it to his own humanity. He wore a series of invented characters bundled up like sweaters on his skin: Ziggy Stardust, Major Tom, Halloween Jack, Aladdin Sane. He’d perform as each of these roles on stage, and he’d sometimes play them in interviews. Each of these characters blurred the lines of gender, sexuality and race: All were difficult to pin down as male or female, white or Black, human or alien. The common thread among all these people was that they were outsiders within the societies in which they lived. And just when you thought they were beginning to find success, each character made themselves a stranger again.

Starman

Take one of the characters that Bowie actually did play as a professional actor, a lead role in Nicolas Roeg’s “The Man Who Fell to Earth” (an erotic psychedelic film released in 1976). The movie is about an alien who comes to Earth and meets a rosy-cheeked girl who works at the hotel where he’s staying. He adopts her as a sort of motherly companion and sex buddy, and after selling a mysterious patent for billions of pounds, buys a mansion for them to live in together. Just when you’re admiring the pair’s strange beauty and thinking they might live happily ever after, the alien shaves off his hair, gets rid of his eyebrows and cuts his eyelids. The poor girl almost has a stroke after realizing she’s been having sex with an alien all this time. Things only get weirder from there.

“The Man Who Fell to Earth” is the kind of project Bowie liked because it got at what it means to incubate a new identity and takes pleasure in crushing your attachments to traditional forms of identity. The character begins almost too perfectly: a naive, beautiful young man who finds love and riches near-instantly: a semi-bastardized version of the American dream. But of course, this cannot last because that is not how real life works. Real life can be more like alien sex: degenerately ascetic, momentarily exuberant, disquieting, distilled. You aren’t always beautiful, and you aren’t always happy: You are a body, a mind and a sequence of events and ideas pieced together into some kind of sequential narrative. Bowie did not have a thin skin, then, but neither did he have a thick skin; he was so impossible to pin down because he wore so many skins at the same time.

Hang On to Yourself

Today, the woke left is obsessed with labels. Brand labels, identity labels, political labels. In grouping people together, this ideology reduces them: It pins people down to a series of extrinsic markers, starting with their skin color, their gender, their sexuality.

Bowie’s lesson to us liberals is that our politics need not be so predictably boring and bureaucratic. Truly blurring the lines of identity—moving beyond the near-mythical status that our societies have granted to these markers—is a personal task as much as it is a political one. A powerful response to years and years of sex- and race-based persecution—a powerful response to patriarchy—would be to reinvent your own identity precisely when you seek to profit from it. When Bowie ridiculed an MTV interviewer for the lack of Black artists featured on the channel, he was simply exposing a hypocrisy: He was not pretending to speak for a cause, nor was he staying quiet about that cause because he happened to be white.

Art’s lesson is that it is impossible to get beyond our own inauthenticity. Human identity is faked through and through. The “real self”—that terrible phrase you hear on advertisements for backpacking trips and cliched Instagram posts—is an illusion. No one knew this better than Bowie, who was a creator of illusions that know they are illusions. We learned to follow him from illusion to illusion.

Of course, this kind of identity play can be downright dangerous. If you treat personas like T-shirts, it’s awfully tempting to try on the craziest personality you can find. One of the characters Bowie invented was the Thin White Duke, an Aryan-looking fascist war commander. When Bowie, playing this role, seemed to glorify Adolf Hitler by calling him the first-ever pop star, it was a sign that he had fallen prey to this tendency.

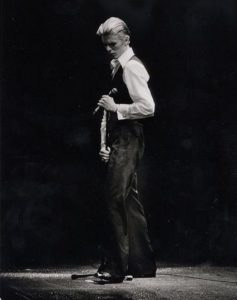

War Commander. Bowie as the Thin White Duke in 1976. Image Credit: Jean-Luc Ourlin/Wikimedia Commons

Choosing to live as a series of characters can also make it easy to lose your grip on reality. Bowie’s brother tragically died during a schizophrenic episode, and though Bowie was never a psychotic himself, the theme of madness was to find its way into much of his artistic work. This meant pushing his mind to the brink of where sane minds can go, a pursuit made far easier by drugs.

Bowie learned this lesson the hard way with drugs, for his drugs of choice were extremely hard. He had tried cocaine before ever smoking a joint. His three years in Los Angeles were spent so utterly intoxicated that he later admitted he’d forgotten the period entirely. This was a period of extreme creative output. It was also a period when he felt like he was constantly drowning.

It is only later in life, when he had grown mellower and quit drugs and alcohol altogether, that Bowie learned how to control these urges. He became supremely restrained, such that he could go on experimenting—go on reinventing himself artistically—without becoming truly lost again. The outcome was one of the longest careers in show business. Bowie had multiple high points as a musician, writer, artist, designer and actor, and these were spread out intermittently across decades. His late relationship with Iman, the Somali fashion model he married in 1992, lasted 24 years, and she continues to fiercely protect his legacy to this day.

Sense of Doubt

But there was one danger—one frailty in the hotchpotch philosophy—that Bowie never quite settled on a way to address. This was the fact of information overflow. Creating your own identity requires time to reflect: You must have faith in the individual’s ability to discern and curate the materials that are shaping who they are.

And yet, in the 21st century, everything is increasingly digital and ephemeral: Truth appears one day and is gone the next. We are each creating and consuming more conflicting data each day than we used to in years. As the science fiction writer William Gibson put it, “The present is gone in the instance of becoming.”

Bowie spent many of his later years thinking about this problem. Upon the release of “Reality” in 2003, he said:

It’s almost as if we’re thinking post-philosophically now. There’s nothing to rely on anymore. No knowledge, only interpretation of those facts that we seem to be inundated with on a daily basis. Knowledge seems to have been left behind and there’s a sense that we are adrift at sea.

In a BBC interview with Jeremy Paxman four years earlier, he had called the internet the real “alien life form.” He was excited by it, but also incredibly scared of it. A world of infinite competing narratives makes it possible for multiple worlds to coexist, but it is easier to cling onto identity markers that have been granted to you than it is to create unpredictable characters on your own. To reinvent yourself, you need to be willing to lose yourself. This is an act of deconstruction. If you are metaphysically adrift at sea, it is easier to subscribe to ideological orthodoxy.

For Bowie, deconstructing yourself did not mean letting go. He was a hoarder and preserved everything—even the keys to his apartment in Berlin. Nor did it mean not believing in anything. It simply meant trying as often as possible to examine and expose the incentives beneath his beliefs.

His response to information overflow wasn’t escape, nor was it to cling desperately onto a single narrative. He always said that he was a writer first and a musician second, and he performed the writer’s, or perhaps the memoirist’s, job: going through his own elongated archives and seeing how his mind turned—discovering how each perspectival change was bound up with life circumstance and habit. In other words, he embraced the mode that the internet made possible: He turned to assemblage and continued to collect and arrange his life’s moments precisely so that he could properly experience them.

Today, the internet is dismissed as a mirage, and the word deconstruction is usually used as a slur—“it is post-truth, post-narrative and post-modernist,” people say. If you deconstruct, the charge goes, you are left with nothing concrete to believe in, no identity to belong to, and you are doomed to nihilism. Bowie was the furthest thing from nihilistic. His form of truth may be inauthentic, insincere and carefully constructed—“assembled from interpretations,” you might say—but ultimately it still feels supremely honest. It is, in other words, a writerly kind of truth: it implores you to become some other kind of person, something freer, weirder, more intoxicating, a chameleon who learns more about himself and the world every time he changes the color of his skin.