“Post-Journalism” and the Death of News

Elites have lost control of the information agenda and, despite the “Trump bump,” they’re not getting it back

Information matters because it sets the stage and arranges the props for the drama of social and political life. It places boundaries on human action. If you think the ship is going to tip over the edge of the world, you are unlikely to sign up for that cruise.

But why should “news” matter? The answer will in part depend on the historical context. In 1920, for many people, news and information were virtually synonymous. A century later, we find that the two categories have undergone a scandalous divorce. Yet from the first, and at all times, there has been a mystique surrounding the news.

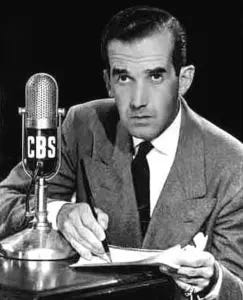

Freedom of the press holds a special place in the liberal canon: James Madison expressed the general sense of the matter when he called it “one of the greatest bulwarks of liberty.” Editors and journalists who labored in this lofty place—think James Reston or Edward R. Murrow—are often portrayed in the heroic style. The stuff they churned out—the daily output of journalism—is never depicted as an industrial product that must be promoted and sold for consumption in the marketplace. Among democratic elites, the smell of newsprint evokes the odor of sanctity.

By the middle of the last century, the mystique had congealed into an implicit ideology. Journalism and the news were said to sustain democracy in two distinct but complementary ways.

By distributing objective reports to the public, they broke through the fog of government secrecy and political propaganda to hold elected officials accountable. Journalists spoke truth to power and exposed corruption at the top. The Watergate scandal and downfall of Richard Nixon were taken to be mathematical proof of this proposition—in the Hollywood version of “All the President’s Men,” investigative reporters assumed the guise of film noir detectives searching for truth in a dangerous and deceitful world. Absent such fearless light-bearers, democracy, we were told, would die in darkness.

Journalists, once considered shiftless scribblers, were also reimagined as political educators to the masses. They brought Washington to Wichita Falls and the world to Main Street. The theory of the “omnicompetent sovereign citizen” required that all who participate in democracy possess a masterful knowledge of issues and affairs. The news met that demand: to devour it was not a consumer choice but a patriotic duty. Kids in public schools were handed copies of Junior Scholastic and urged to keep up with “current events.” It went without saying that they would grow up to be newspaper subscribers. After all, the road to political wisdom led directly through the news, and the daily paper delivered all the news that’s fit to print.

But between the ideology of news and the reality of the news business, the distance was breathtaking. Far from speaking truth to power, the news was the means by which elites communicated their interests and intentions to a vast but silent audience. Rather than saviors of democracy, investigative reporters were bit players in the elaborate games of the political class. Watergate, properly understood, was a minor adjustment within this group—an intramural scrum. Nearly 50 years later, nothing much has changed.

Newspapers had little incentive to educate anyone. They needed to attract eyeballs that they could then sell to advertisers, and to this end they bundled together stories about wars and movie stars, earthquakes and baseball games, as well as comic strips, advice to the lovelorn, astrological predictions and crossword puzzles. Purchasers of this bizarre agglomeration of content were not to be frightened with the ugly truth but gently herded into a bland consumerist mass.

Still, the mystique has a powerful hold. The news media’s schizophrenic disconnect between cherished ideals and actual business practices has survived many disasters, and this disconnect was never more vividly manifested than in its love-hate relationship with Donald Trump.

Andrey Mir, Tour Guide in Information Purgatory

The digital tsunami that smashed into modern society around the turn of the century sent the ideology of news into a state of perpetual crisis and dealt the newspaper business model a possibly fatal blow. Elites lost control of the information agenda. How, then, could they explain the world to the masses? Old monopolies vanished in an instant as advertisers fled online, never to return. Who, then, would pay for the news? What would become of democracy if no one spoke truth to power?

Such questions gained a frenzied immediacy after Trump’s 2016 election to the presidency, an event many to this day (and against all the evidence) believe was caused by the seeding of “fake news” on social media. But if news could so easily be faked, what did that say about it as a form of information? And, in the darkling plain of clashing narratives that is the web, how on earth could one discern the authentic product?

When it comes to the news and information generally, we are in desperate need of a guide through the chaos—and we are fortunate that one has arrived on the scene. Andrey Mir is a Russian-born journalist and media scholar who has lived in Toronto, Canada, for many years. His 2014 essay, “Human as Media: The Emancipation of Authorship,” analyzed in 100 pages the properties and dysfunctions of the digital realm. It’s a little masterpiece that should be read by each of the 4.6 billion persons who stumbled online in 2021.

Mir’s latest book, “Postjournalism and the Death of Newspapers,” is a more ambitious project. Weaving together a mix of memorable epigrams, amusing anecdotes and masses of data, “Postjournalism” follows the 400-year story of the news from its birth in 17th-century Venice and Germany to its mortal agonies at the present time. The perspective is always analytical. Everything is explained. What Walter Lippmann was to the age of newspapers and Marshall McLuhan to that of television, Mir should become for us today: our Virgil in the purgatory of the information landscape.

As can be inferred from the title, “Postjournalism” was not written to raise the morale of dispirited journalists. Mir sees nothing but doom ahead. With the defection of advertisers, the market long ago left newspapers behind: ad revenue, he informs us, fell from $65 billion in 2000 to $12.3 billion in 2018, and the hemorrhage continues to this day. There is no economic rationale for the newspaper today, but there remains, Mir observes, a social rationale. The “myth of the newspapers’ significance . . . held by the older generation and desperately promoted by the newspapers themselves” will infuse the latter with a vestigial existence for a few years.

The final blow will come from an irrevocable demographic transition. Older readers who can’t imagine democracy without newspapers will die off. Members of a younger generation, late millennials and Zoomers, have never held a physical newspaper in their hands and have no idea how to or why they should subscribe to one. When they arrive as the main consumer force, the newspaper will expire. Mir even foretells the time of death: the mid-2030s, after which “newspapers will become historical artifacts.”

The consequences will be profound. We tend to assume that newspapers, somewhat mutated, will endure online. That vastly underestimates the importance of form. “The physical limitations of newssheets,” Mir tells us, “caused a need for selection. This news selection led to the creation of editorial policy.” Editorial policy, in turn, evolved into the ideology of news. In the wild churn of the web, there are no limitations, no need for selection, no way to impose a standard or ideal to separate the important from the trivial, the excellent from the flawed or even truth from falsehood. The mystique will simply implode under the pressure. The “extinction-level event” that has overtaken newspapers will mean the end of journalism and the death of news.

The “Trump Bump” and the Art of Commodifying Polarization

A funny thing happened to a handful of big-name news providers on the way to extinction. They ran into Donald Trump. From their first encounter in the 2016 Republican primaries, the largely liberal news media loathed Trump politically but loved the effect he had on readership and audience growth: what Mir labels the “Trump bump.”

Under the pretense of saving democracy from a would-be Mussolini, the media lavished unprecedented levels of coverage on Trump. Mir provides the numbers. They are extraordinary. As candidate or president, Trump never had to out-debate his opponents; he could just bury them in the obscurity of his immense shadow. (His downfall came when the COVID-19 pandemic snatched away media attention and became an even more towering story. The model was the same, however. In many ways, COVID-19 was covered as the Donald Trump of diseases.)

Covering Trump demanded a new style of reporting. The pose of objectivity was explicitly abandoned. A journalism of open advocacy replaced the old ideal of a journalism of facts. This, Mir rightly notes, was a knock-on effect of the web, a medium so overwhelmed by noise that even facts assume the aspect of opinion. Mir has christened this new style of shrill, self-righteous advocacy “post-journalism”—and he views it as a desperate gambit for survival.

Here we are back to the question of why anyone living in the 21st century would pay for news. Advertisers are gone. Ordinary people get their information from social media feeds. It would occur to no one under the age of 80 to go to a newspaper to catch up on a late-breaking event. What commodity could newspapers offer for sale? Post-journalism provided the answer: it commodified Trump.

Or, as Mir insists, it commodified polarization. Not only was Trump opposed, but he was portrayed at every occasion in terrifying terms, as a demonic figure whose latest tweet might well destroy the nation and whose legitimacy no decent person could accept. “Postjournalism must scare the audience to make it donate,” Mir writes. “This is the role of negativity under this business model.”

Post-journalism, in truth, is a business model concealed behind an ideological stance. It sells a creed, an agenda, to like-minded believers. It identifies the existential fears of a specific audience, then manufactures what that audience will buy. And for a few big media brands, that business model has succeeded beyond their wildest dreams. The Trump bump is real.

At the start of the 2016 presidential campaign season, the roster of The New York Times digital subscribers languished at under a million with flat growth. Today the Times has 7.5 million digital subscribers, the most in the world for any newspaper. The Washington Post and the cable news networks rode a similar, if less spectacular, trajectory. “Donald Trump,” Mir quips, “made the American mainstream media great again.”

But that holds true only for five or six newspapers and broadcasters with a national reach. There can only be so many prophets in the Church of Anti-Trump. Partisan subscribers have no wish to subsidize propaganda that few will read. Post-journalism has done nothing to stop the traumatic collapse of the local newspaper, and it may be aggravating their condition as remaining readers concentrate their support on famous brands.

Even these big-name outlets face an uncertain future. Donald Trump may have been the P.T. Barnum of modern American politics and his White House the strangest show on earth, but everyone knows that eventually the circus folds its tents and departs, leaving the townspeople to resume their humdrum daily lives. Commodifying polarization without Trump may be impossible. Manufacturing anger under the soggy political aura of Joe Biden seems unlikely to generate a profit.

Already there has been a steep decline in cable news viewership; there’s now talk of a “Trump slump.” The advance of demographic doomsday hasn’t been delayed by an instant. Mir appears confident (so far as I can tell, he is never not confident) that post-journalism has been a mere convulsion on the way to the grave and that the giants of newsprint will soon become museum pieces or playthings for billionaires.

Mir’s analysis contradicts the received wisdom that our information environment is divided between fact-bearing, democracy-preserving traditional news and the rabid nihilism of social media. True, social media profits greatly from polarization. As Mir notes, it fosters that most precious digital commodity, engagement. But traditional news is equally dependent on polarization to lure converts into the sacred garden beyond the paywall. On the scales of nihilism, both tip down on the same side.

Structurally, few corners of the information landscape can be found that do not incentivize rant and aggression. Worse still, polarization is never steady-state. It must lead to ever-increasing levels of agitation or the public’s attention will wane. Democracy must be portrayed as a criminal conspiracy. Politics must turn into an endless conflict between raging war bands. In this crossfire of political fantasies, facts and truth, when they appear before us, are wielded only as weapons of war.

Post-Journalism and the Flight From Truth

“The hypothesis that seems to me most fertile,” Walter Lippmann wrote in Public Opinion a century ago, “is that news and truth are not the same thing, and must be clearly distinguished.” Truth, for Lippmann, revealed “the hidden facts.” News, while not necessarily lies, could not escape being “fiction”—stories told by self-interested parties. Lippmann despaired that the public must always be duped by political and media elites manipulating emotional episodes against a background of stereotypes.

The fake news controversy that has tormented our political life since 2016 should be placed in historical perspective. It assumes a lost Camelot of journalism that never existed and refers to an ideology that is itself one of Lippmann’s fictions. In the old dispensation, elites controlled the agenda. That gave news a certain definable shape and great prestige. To “make the news” meant you were at the top of your field, even if you were Osama bin Laden or Al Capone. Definition and prestige felt like truth, at least if you didn’t look too closely.

The destruction by the web of this information-gatekeeping mechanism has been primarily a crisis of the elites. Ordinary people experienced it as an expansion of reach—the emancipation of authorship, in Mir’s phrase. With more than 4 billion authors now telling their tale, definition and prestige have been lost in the uproar and the agenda has slipped beyond anyone’s control. And as always when the high mingle with the low, judgments have been passed. Traditional journalism perpetrated an immense number of silences, fictions and outright lies: but these were consensual affairs. Lies erupting from below, to the elites, feel like an assault.

Mir cuts the knot of contradictory claims and denials with a startling formulation. “Social significance in media,” he asserts, “is not a function of reality reference or selection; it is a function of dissemination, of a scale of reach.” If truth must be validated against reality, news can only be validated by dissemination: information not shared at scale has little value. From a sociopolitical viewpoint, it doesn’t exist.

With the collapse of elite authority, however, truth itself is now up for grabs, and we stagger heedlessly into the murky bog of post-truth—“the validation of reality through attitudes toward it.” Post-journalism and fake news arise spontaneously in this environment. Both seek to impose a subjective attitude on reality and to conquer significance through dissemination. The result is a world of surprises. Sectarian war bands such as QAnon and Wallstreetbets can ride the unstable reality of the information sphere to achieve powerful real-world effects. Trump, the grand master, played this game all the way to the presidency.

Post-journalism is the genteel institutional face of the flight from truth. The New York Times, for example, published literally thousands of articles that found Trump and his inner circle culpable of criminal collusion with Russian agents to subvert the 2016 election. Detestation of Trump, rampant in the Times newsroom, was superimposed on objective reality. After the Mueller Report found the collusion story to be wholly devoid of content, there was no soul-searching, no sense that the Times had incurred a journalistic disaster. In fact, it had enjoyed a post-journalistic triumph. Millions had crossed into the paywalled garden to be reassured of Trump’s guilt: here was validation by dissemination.

None of this would have shocked Walter Lippmann, who understood that, unlike hard reality, the news exists in a constructed world that can be altered to seduce the reader. The inevitable question is whether we should follow Lippmann into despair—whether the rise of post-journalism and fake news mirrors a fundamental failure of our system.

Can Democracy Survive the Death of News?

The current demand for information is unlikely to disappear. The market will move to satisfy it as it now satisfies the craving for entertainment. The death of news will not be a silence but a Cambrian explosion of new informational forms. That process has already begun: consider the popularity of podcasts and Substack-style newsletters. Mourning “journalism as we knew it,” in Mir’s words, is futile. It had good reasons for committing suicide. The forced extinction of post-journalism, Mir makes clear, will simply remove a source of polarization and escapism from democratic politics.

Madison’s “bulwark of liberty” defended the right to criticize entrenched power before an audience without fear of repercussions. In the age of the rant, that right is scarcely endangered. The trouble lies elsewhere. The long, melancholy withdrawal of the news has exposed a severe structural weakness in our political machinery—one that appears very different at the top and the bottom of the pyramid.

At the top, the agony of the news has been experienced as a wrenching rupture between the governing classes and the public: a wound that will not heal. The elites have a functional need to be heard, which the news once met. A deafening Babel of voices now contradicts and drowns out their every utterance. The dazed response has been retreat and reaction. The elites wish to return to the 20th century, that golden age of top-down communication, but every step toward the past increases both their distance from the public and the public’s suspicion of their motives. The bonfire of the journalistic vanities has formed part of the lurid background to a decade of revolt.

The wound, however, is self-inflicted. The information sphere teems with platforms of communication: that is its most typical and abundant feature. The governing elites are not forbidden or unable to speak. They are unwilling to compete for attention. They dread the thought that the public will shout back. This phobia has been the strategic advantage of populists like Trump, who achieve proximity with the public by engaging with it on digital platforms. Until more constructive politicians master the art of online communication, the crisis of the elites will only deepen.

Separated by an impassable gulf from the elites, the public must now fend for itself in a digital polity Mir compares to “direct democracy.” “People speak their minds,” he writes. “Not just sanctioned people, or the rich, or elected officials, or the educated—all people.” But speaking, Mir admits, is not the same as listening—much less understanding. The crisis of authority that killed the news has also alienated the denizens of the digital city from each other, until the only common ground is the repudiation of reality.

The web is nothing if not movement—a great host of shadows advancing blindly on the unknown. The urgent question is how to find true north. Truth by dissemination feels like a volatile and transitional state. We are headed somewhere, driven by a powerful yearning for community.

The concern of some is that demagogues will exploit the death of news and the proliferation of fakery to lead the public to an anti-democratic destination. That is possible but unlikely. To the best of our knowledge, the human mind is a difficult object to budge: even the purveyors of post-journalism pander to preexisting tastes. The image of an easily manipulated public is favored by elites in need of reasons to justify their own existence. For Lippmann, who first drew that image in the context of modern politics, elitism was practically a religion.

The public is perfectly well informed and more intractable than ever, but it will have to transcend the toxic unreality of the information sphere if it is to bring democracy safely into the 21st century. The long march in the wilderness appears aimless, but it has a promised land: truth, validated by fixed points of reference rather than subjective attitudes or dissemination at scale. Having abandoned the centrality of news and the consensus of the elites, the public today can be described as 4.6 billion characters in search of a plot—an alarming adventure that I hope will usher forth more brilliant explanations from Andrey Mir.

For more on post-journalism, see Martin Gurri’s interview with Andrey Mir.