Pluralist Points: Citizen Checks on Presidential Power

Corey Brettschneider talks with Ben Klutsey about how the presidency is a point of vulnerability for our democracy

In this episode of the Pluralist Points podcast, Ben Klutsey, the executive director of the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, speaks with Corey Brettschneider, a professor of political science at Brown University, about his new book, “The Presidents and the People: Five Leaders Who Threatened Democracy and the Citizens Who Fought To Defend It.” They discuss the early presidential models of Washington and Adams, what categorizes a “recovery” president after a period of crisis, Frederick Douglass as a founder of American democracy, how we haven’t yet recovered from Nixon and much more.

BEN KLUTSEY: Thank you for joining Pluralist Points. Today we have Professor Corey Brettschneider. He’s a professor of political science at Brown University, where he teaches constitutional law and political theory. He is the editor of the series Penguin Liberty and the author of numerous articles in top political science journals and law reviews, including the American Political Science Review, Political Theory and the Texas Law Review. His constitutional law casebook is widely used in classrooms throughout the United States.

Some of the books he’s written include “When the State Speaks, What Should It Say?: How Democracies Can Protect Expression and Promote Equality.” His other books are called “Democratic Rights: The Substance of Self-Government” and “The Presidents and the People: Five Leaders Who Threatened Democracy and the Citizens Who Fought To Defend It,” which is the subject of our conversation today. Thank you for joining us, Corey.

COREY BRETTSCHNEIDER: Thanks so much for the invite, Ben, and I’m really looking forward to the conversation.

Our Fragile Democracy

KLUTSEY: Great. Now, one of the things I notice you highlighting in the book is the idea that this democracy is fragile. Is it fragile or resilient, or both? I hear both things from time to time from scholars, thinkers and thought leaders who are trying to encourage us to do the hard work, to work to preserve it and not take it for granted. I’ve often wrestled with the question, how fragile is it? What is the level of resilience of our democracy? What are your thoughts on this?

BRETTSCHNEIDER: Certainly, it is fragile. That’s part of the point of the book, that there is a warning, really, at the founding from Patrick Henry. Of course, Patrick Henry, as listeners will know, is a revolutionary hero. He also opposed ratification of the Constitution. He opposed ratification because of the fragility of what he thought this new constitutional system would bring. Specifically, it had a particular vulnerable point that he was worried about its fragility, and that was the American presidency.

His argument is that this office is so powerful that it assumes a good person in office. If you get a bad person, a criminal president—and a criminal president not just in the sense of criminally minded in a petty criminal way, but one who’s got grand ambitions for their crimes—they’re going to realize that the traditional checks on the office, the judiciary impeachment, that those don’t work—the formal checks, maybe would be a way to put it.

Actually, now this is the part that I think, to many, sounded paranoid at the time and might have seemed paranoid until somewhat recently: that they are going to realize that without the checks, that they can aggrandize power, so much so that they might even—and this is the wild part—crown themself a monarch. Now, that’s his warning against ratification.

What I want to say is, American democracy has certainly survived. It hasn’t collapsed. We’ve had moments where any recognizable sense of it was at risk. It was at risk for Henry’s reason. The American presidency has always been a danger, and we’ve seen it. I talk about five previous times in American history where there was a real vulnerability to its collapse from presidents who threatened it. You ask about survival. I don’t think I’d use the term “resilience” because I’m always worried about the idea that somehow the Constitution is self-correcting or that it’s such a genius document that the intended checks—impeachment and the judiciary, for instance—are definitely going to work.

Instead, I think what’s happened is that at these moments of crisis, that the recovery has come through a combination that the framers really didn’t anticipate. That’s both citizens forming what I call constitutional constituencies looking to save a democratic idea of the Constitution. And in a particular way, partly by voicing these ideas in ways that America will come to understand, but then channeling the energy behind these ideas, this democratic recovery idea, by electing subsequent presidents.

The thing that makes us vulnerable is the American presidency. The thing that’s allowed us to recover is also the American presidency, not acting on its own, but at the behest of these democratic constitutional constituencies. That’s the argument of the book. Part of what I want to say is, definitely, this should give us hope in the ability of American democracy to survive, but it also shows its vulnerability at the same time.

There’s a grade-school, traditional way we talk about checks and balances. I want to say, those checks and balances really are not the thing that’s worked to save us at the direst times. It’s these citizens acting. It’s partly about agency, that we shouldn’t assume a mechanism that’s automatically going to save us. There’s no Constitution police. What is there? There are citizens who really can take matters into their own hands to save democracy.

Washington and Adams

KLUTSEY: Right. Do you think that the founders were thinking too much about George Washington as a model because of the character that he had when they were thinking about the president, that that overshadowed their thinking?

BRETTSCHNEIDER: Absolutely. You took the words out of my mouth. They watched him preside over the convention. They respected him. To my mind, he gives one of the most ideal understandings of the American presidency when he says at the founding, “Look, I’ve just taken the oath of office”—this is in the second inaugural—“I just took the oath of office. If I violate it, I want the people assembled here to call me on it by criticizing me, upbraiding me.” He says this in a much pithier way than I am, actually—shortest in American history. He says, “If I really mess up, I want you to subject me to constitutional punishment.”

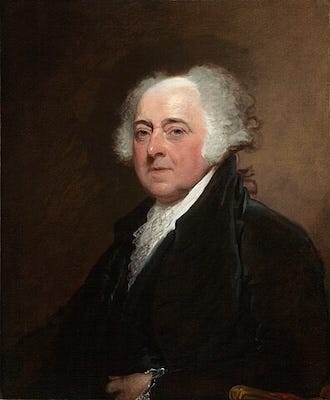

Think of the kind of person that would do that. They really see the office as an office subject to the Constitution and the rule of law, and subject to criticism. Yet he’s replaced. The second president is very different than Washington by, as you know from the book, John Adams, who really has a totally different understanding of the office: a kind of quasi-monarch, not subject to criticism. In fact, he tries to enforce his idea of the presidency with the Sedition Act.

KLUTSEY: Yes, which is a great segue, because that was going to be my next question about Washington and Adams coming back to back. These people have such different personalities. Adams has this royal envy, and the idea that the president might be called “his highness” (I think super very strange), and sought to enlarge his powers.

What accounts for this difference? Maybe it’s obvious; maybe it’s just a matter of personalities. The kinds of people who seek that office might be prone to certain kinds of personalities. Washington didn’t necessarily have it, although maybe he had it but exhibited in different ways. I think you mentioned in the book that he was a really wealthy businessman, and he focused on those things rather than enlarging his powers as president. Is this simply just personality differences?

BRETTSCHNEIDER: I think it’s part of it, definitely, that Washington really had this modesty that reassured people when they were crafting the office itself. That’s a lot of why they were a little naive, I think, in the way that they thought of a president. Adams is not really like that. He’s thin-skinned. When his son is criticized, when he’s criticized, he feels it, and that’s part of the idea of the Sedition Act. It’s more than that. Adams looks down on Washington because he’s got a folksy, commonsense way of thinking. He’s not a scholar. Adams is a political theorist, a constitutional lawyer, one of the premier thinkers about these issues, that we all teach and write about, of his time.

Yet in the content of the way he thinks about it, I wouldn’t call him a democratic thinker. He doesn’t think of “we, the people” as the sovereign entity to which all the branches are subject. That’s not the way he thinks about things. Eric Nelson and others who have really written about his royalism, and Gordon Wood also—there’s consensus, I think, about Adams, although disagreement about how widely spread these ideas were at the time. He has a philosophical idea of the president as a quasi-monarch, justified by reference to Montesquieu in terms of the stability that this office will bring, as opposed to the House, which really is grounded in the will of the people.

When it comes to sedition, he says what a lot of Federalists said at the time, which is that the Sedition Act is consistent with the common law. There’s some free speech, but not a right to criticize the monarch. In the same way, by analogy, there’s not a right to criticize the president. There is a widespread belief at the time that when the Sedition Act is introduced, even though it really does shut down criticism of the president—by the way, it’s tailored to allow criticism of the vice president, a member of a different party—

KLUTSEY: Right.

BRETTSCHNEIDER: —Thomas Jefferson, a very partisan attack on the opponents. But it’s seen as constitutional because it’s not prior restraint; it’s punishment after the fact. That seemed as consistent with the common law. I wish I could say, okay, it was just these thin-skinned presidents who threatened democracy because of their personalities. No, there are deep ideas of what I call an authoritarian idea of the Constitution that are behind them. Adams, the first threat to democracy that I talk about, really has that in depth. He’d be sitting here defending his view against me. It’s not that it’s not thought out, but it is partly dangerous because it’s so thought out.

The Sedition Act

KLUTSEY: Yes. Now, Adams helps to establish the Sedition Act. Is there anything more egregious in terms of silencing dissent than the Sedition Act?

BRETTSCHNEIDER: I think it’s the use of it. It’s partly you see its offensiveness, its threat to democracy, and its content, as I said, is gerrymandered really to go after the opposition party. You see that in the fact that there’s no punishment for criticizing the vice president; there is for criticizing the president.

I think sometimes scholars, at one point, were writing about it as if it was seldom used, but it’s about as many as 126 prosecutions. When you start looking into them, they’re pretty egregious. They include Matthew Lyon, a sitting congressman from Vermont who’s prosecuted largely for stuff that he says on the floor of the House, and the main opposition editors who are really criticizing Adams and his policies.

One of the worst things about it is what gets it off the ground, is that there was a report of a plot to usurp the election of 1800 by the Federalists. It sounds eerily familiar because the way the plot worked was, there was going to be a committee to deny the certification of electoral votes. Under the Constitution, of course, if you can’t get to the threshold required by the Electoral College, it throws it to the House, and the Federalists thought they could win in the House. Anyway, it’s not really a secret plot because it’s discussed on the floor of the House. When it’s published by one of the editors, that freaks out the Federalist Party, and the act is partly in retaliation for that.

There’s a personal element as well. There’s—I talk about Abigail Adams corresponding with her husband, John Adams, about the fact that their son is being subject to attacks, and that seems to have touched a nerve for both of them. It’s a variety of elements. It’s pure politics, really trying to undermine democracy in the rawest sense through this plot to usurp the election and retaliation for uncovering it. It’s thin-skinnedness, as we started out talking about.

Then to my mind, again, the most dangerous thing is the philosophical, authoritarian idea of the Constitution. By the way, it’s not that they didn’t know, of course, the First Amendment had been passed. There was a right to free speech under the First Amendment, but they thought you read it consistent with the common law. It allows for the prosecution of criticism of the president, of sedition.

Chaos and Recovery

KLUTSEY: Yes, the entire story is really fascinating. Now, in the book, you outline this cycling of crisis or chaos and recovery.

BRETTSCHNEIDER: Right.

KLUTSEY: I wonder, is this an inevitable aspect of democracy?

BRETTSCHNEIDER: No, I don’t think so. I think this goes back to our first exchange. I wish. That would be great if I could say, “Don’t worry, everybody, it’s guaranteed to work.” No, it’s not a formal mechanism. It doesn’t operate in the way the framers thought impeachment, for instance—they thought, look, impeachment, if somebody commits not just a crime-crime, but a high crime and misdemeanor, an act so grave that it’s an abuse of power that really threatens the whole system, then everybody is going to come together, and the majority will vote in the House, two-thirds of the Senate. We don’t want it to be partisan, so that two-thirds will protect us. Then there’ll be a disqualification vote. End of story.

Of course, that’s never fully played out. Maybe the Nixon case (we can talk about it) it played a role. But nobody has ever been removed from office and disqualified in the history of the United States, despite these moments where it should have been used, in my view. What has worked are the citizen actions, constitutional constituencies coming together to elect recovery presidents.

But what I’m trying to emphasize throughout the book is it really rested on these—people in interviews have been calling them “constitutional heroes.” I like that. I don’t use that phrase, but it’s agents who really rose above the moment and did something heroic. We haven’t gotten to Frederick Douglass. He is really chief among them, but the editors certainly are among them. What they did that was pretty extraordinary is, in this moment of crisis where they’re facing their own prosecutions, they use their trials to try to defend the idea that the First Amendment right to free speech is a right to dissent. They use their trials to try to put Adams on trial and to say, “This is an authoritarian president.”

They’re really recovering and claiming the democratic idea of not just free speech, but that what that means is a right to criticize the president. We’re so used to “Saturday Night Live,” and this is part of our culture, that of course you can criticize the president. They’re really creating it at the moment. Was that inevitable that it played out that way? No. Probably if you had to bet at the time, Adams looked pretty strong.

Again, Adams—and this is true of many of the presidents in the book (Wilson, certainly)—there’s an authority to him. Still, when he’s talked about—think of McCullough—we revere him for his learnedness. I’m not going to deny that. I don’t know. As a political theorist, I read a lot of the work. It’s a little meandering. It’s a pretty good dissertation, but is it great? Not in the way that people have claimed because it really is an assault on democracy. It’s dangerous for that reason.

KLUTSEY: Right. I guess the thing that’s also interesting: You cover presidents that cut across the labels, right, the political labels?

BRETTSCHNEIDER: Yes.

KLUTSEY: Woodrow Wilson was a Democrat, and Nixon is a Republican. These are things that they’re characters that, regardless of what party, the president can exhibit, which is not good.

Qualities of a ‘Recovery President’

KLUTSEY: In moments of national crisis, the president’s role becomes even more pivotal. What are the qualities of presidential leadership that have historically led to successful navigation through crises? These recovery presidents, I guess—what are the core features that truly make them recovery presidents?

BRETTSCHNEIDER: That’s a great question. The features aren’t exactly inverse, but many of them are. One is responsiveness to the constituency. Even though that sometimes might be seen as pandering, but there has to be a kind of openness.

Was Jefferson, in his heart, a true defender of free speech? I’m not sure, but he’s elected on this idea of letting the Sedition Act expire and not return. When he says, “We’re all Federalists, we’re all Republicans,” he’s really celebrating the editor’s idea that we’re not going to prosecute dissent in this country. He secretly has a lot of the flaws of the worst presidents and privately seeks prosecutions, for instance, of his opponents. At least the idea is recovered.

In Madison, you really get somebody who I think of in many ways in the tradition of Washington: that he’s restrained, he’s modest. Even during the War of 1812—this is the great triumph in the early republic for free speech—he has this chance. This is actual war, as opposed to a kind of quasi-war in Adams’ time. He could say, “Okay, this is different. Real war, we’re going to shut down dissent.” He doesn’t. He listens to the opposition party—a newspaper editor named Hanson, in particular, who’s facing attacks on his life—and refuses to institute a new Sedition Act.

In some ways, it’s that there’s a more folk morality with some of these recovery presidents, as I call them—and thanks for using my term, too, for listeners—as opposed to this grandiose vision of the Constitution.

I’m thinking of Truman, in particular, in the last cluster. As you mentioned, Woodrow Wilson really brings about a new crisis of democracy by nationalizing white supremacy and trying to nationalize it and succeeding in large part, not just by showing “Birth of a Nation” in the White House, but really by providing, in many ways, the roadmap for this cultural idea of white supremacy and resegregating the federal government. Even in the midst of what’s about to become Red Summer, using very heated rhetoric that, to say the least, doesn’t help things.

The recovery really doesn’t come for decades. It comes largely as a result of the NAACP’s activism and unknown heroes that I talk about, like Sadie Alexander, who also certainly wasn’t a partisan Democrat—was a Republican, actually, for most of her life. Truman, who had been chosen as FDR’s vice president because he used the N-word and showed lots of signs of being a bigot that was going to go along with Southern white supremacists and certainly not upset that racial order—he emotionally reacts when Walter White and others tell him the stories of how Black soldiers who are coming home from the war are being treated, in some cases killed, in other cases violently beaten almost to death.

They give these images in a vivid way, and it works. That’s what they’re surprised by. Truman, really this person who was appointed because of his racism, just hears how soldiers—who, of course, he’s identifying with as commander in chief, after the war—are being treated. Yet he doesn’t know what to do. He has that openness, really wants to be guided. The committee that’s created by him and Walter White and others, and includes Sadie Alexander (in many ways the hero of that chapter)—it is a modesty combined with openness to hearing the voices of these constituencies.

Garrison and Douglass

KLUTSEY: Right. The story of William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass, I think, is one of the most interesting stories to me in the book. They were both abolitionists, but one wanted to destroy the Constitution, whereas the other wanted to preserve it. Douglass wanted to preserve. Can you describe that for our listeners? I guess for Douglass, he thought, despite the issues, it had the three fundamental rights that you talk about, which is equal protection and freedom to dissent and rule of law that could apply to all, that was still worth preserving. Can you unpack that for our listeners?

BRETTSCHNEIDER: Yes, sure. Thanks. Adams presents this first crisis in the recovery times, as we’ve discussed, with Jefferson and Madison. Then the second crisis is that President Buchanan lobbies, secretly, the Supreme Court. He’s publicly proclaiming this deference to the court, that it’s the court’s job to tell us what the Constitution is. “I’ll go along with what they say as they’re considering this question of the status of Black Americans under the Constitution.” Secretly, he’s saying something very different. He’s lobbying the court, what becomes the Dred Scott case, to say Black Americans have no status, no legal personhood even, under the Constitution.

Now, how do you respond to this crisis of Buchanan and the court going along with him? There are two responses. In some ways, the most natural is to say what William Lloyd Garrison says, as you said, which is, “Wow, this Constitution is terrible. It leads to this awful conclusion that Black Americans are not even people under the Constitution. This is a pact with the devil, and let’s get rid of it.”

What’s so interesting about Douglass, who I really celebrate as the true founder of American democracy—of course, he’s not an 18th-century founder, but he’s rethinking the Constitution in the way that Americans now, I think, should look to as the true meaning of the Constitution—he’s looking at the document itself, the original Constitution. At first, he’s really a mentee of Garrison and is thinking along his lines, but as he comes to study the issue, he breaks with him in a dramatic way, famously dramatic. It’s over this issue of how to read the document.

Douglass starts to say, “Look, the word slave doesn’t appear in the Constitution. What appears are principles that are generalizable and universal.” And most important for the purposes of the book and for his arguments is the preamble to the Constitution, the first three words, “We, the people.” Douglass is telling, “It doesn’t say, ‘We, the white people.’ It says, ‘We, the people.’ It pronounces the principle.”

Douglass uses that as the way in to criticize the Dred Scott case in a very different way than the Garrisonians. The Garrisonians are essentially, about Dred Scott, saying, “Yes, that’s the right interpretation of the Constitution, and that’s why the Constitution is evil.” What Douglass is saying is, “No, it’s the wrong interpretation of the Constitution, which is really rightly understood as a democratic document.”

He goes so much further than that. It’s not just that Black Americans have legal personhood under the Constitution; it’s that there’s an entitlement to (and he often uses this phrase) equal protection, the words that would become the words of the 14th Amendment. And really, equal citizenship is what he means, equal political voting power. His arc, the arc of that recovery, partly with Lincoln—of course, I talk about the dialogues with Lincoln, and how Lincoln was pretty far from Douglass’ view, but at the end of his life comes pretty close to it.

It’s really in the presidency of Ulysses Grant, not just the passage of the 15th Amendment, which he adamantly supports, but the Enforcement Acts and the prosecution by the Grant Department of Justice of more than 1,000 white terrorists throughout the United States. All of this is really incredible, Douglass’ vision from so early on in the 1850s, realized over the decades of Reconstruction.

KLUTSEY: Right, because it could have gone the other way. He could have just simply said, “No, what Garrison says makes a lot of sense. We ought to burn it all down.” He says, “Wait a second. There’s something that we could recover because the principles could be universalized across the board,” which I find, very, very fascinating.

No Recovery After Nixon

KLUTSEY: On Nixon, I think that one of your contentions in the book is that we didn’t truly recover, or we didn’t get this recovery leadership as we would typically in previous experiences, where we’ve seen an affront to the principles and then we’ll have a leader collaborating with citizens to help restore things. Can you say more about that?

BRETTSCHNEIDER: That’s right. That’s part of the reason why there isn’t resilience in the way that I was resisting a little bit, or an inevitability, certainly, of recovery. There’s hope of it. That’s the idea that we really never fully recovered from the Nixon presidency. The story that I tell is of the potential recovery. It still could happen. Remember, these recoveries sometimes take decades.

KLUTSEY: Take a long time.

BRETTSCHNEIDER: When I say we haven’t recovered, that’s not the end of the story. We might be in the midst of it right now. Just to set this up, the crimes of Nixon, first of all—and Watergate buffs will know this—are not just the break-in. They’re so much more than that. They really were an attempt to shut down dissent. The ongoing investigations at the time of the pardon included the attempt to incapacitate, as he [Ellsberg] told me in an interview shortly before his death, Daniel Ellsberg, who Nixon was really obsessed with.

We know now, too, from the tapes that Nixon ordered the break-in at a safe in the Brookings Institution, which he thought had damaging information about his working secretly with the Viet Cong before the election, and was so worried about it that Kissinger at one point on the tape says, “Mr. President, if they shouldn’t have this information, we should go to court.” He says, “No, Henry, I want it done”—I’m quoting his word from the tape—“on a thievery basis.”

It’s wild stuff that he was involved in. This was being investigated. The grand jury that was looking into it—and they’re fascinating to me, too, because they are average citizens of Washington, D.C.: postal clerk Harold Evans; a legal secretary, Elayne Edlund; and led by the head of the grand jury, the foreperson, Vladimir Pregelj, a researcher at the Library of Congress. They were looking into these crimes and hearing from so much of the evidence. They make the decision, they have a straw vote, and Edlund actually says in one interview, some of them with two hands raise their hands to indict the president.

Jaworski, who had been appointed in the aftermath of the Saturday Night Massacre to replace Archibald Cox, who had been fired, convinced them not to do it. He partly said, “I think a sitting president is immune. That’s never been decided, but that’s my view. Could be the case.” He said wildly, “If you indict him, this president is so dangerous, he might have a coup. He might surround the White House with troops to avoid arrest.” Anyway, he backs them down, all with the thought that, of course, after he leaves office, there’ll be an indictment then.

They do participate, I should say, in forcing that president down by handing over all the information in what’s called the Road Map to Congress. And that’s used in the impeachment, resulting in the pressure that led Nixon, after the vote in the House Judiciary Committee to impeach and was never impeached by the full House, to step down. They come back and Pregelj, in particular, is like, “Okay, let’s indict the president.” As I tell it, that information makes its way to the White House. Soon after, the pardon follows. The pardon is clearly an attempt to stop the indictment that’s looming.

The idea of the book is, look, these citizens—and Nixon very much fits the pattern, obviously: famously paranoid, but also he had a philosophical idea of authoritarian constitutionalism. He said, “We’re in a war. It’s a war between the protesters and the silent majority. In a civil war, the president has emergency powers.” When he says that when the president does it, it’s not illegal, he’s not just saying that off the cuff. It’s a thought-out view. He explains it, actually, even in the interview with Frost: Lincoln did this, and the president has emergency powers.

It’s talked about as if it was like a got-you moment where he lost his patience. No, it’s—he has an authoritarian idea of the Constitution. Their idea really stands in contrast. Their idea is simple. In the same way that there’s a right to dissent (the first cluster, the editors, stood for), in the same way that there is an idea of equal citizenship (Douglass’ idea that we talked about at length), their idea is that a president is not above the law, full stop.

I talked to two of the grand jurors who are still alive, not young people.

KLUTSEY: Wow.

BRETTSCHNEIDER: During COVID, actually. I spoke to them on the phone. The way they talked about it was just common sense. “He committed a crime, of course he should have been indicted.” That’s what they’re about now with the immunity decision. We have Nixon’s idea of the authoritarian Constitution, not fully realized, but there are elements of it that have moved us further away.

I really believe that part of the recovery from Nixon has to be the possibility that not only former presidents but sitting presidents can be indicted. That’s something that, talking about bipartisan, that the Biden administration could fix right now. There is a policy of the Department of Justice that says sitting presidents can’t be indicted. He can reverse that.

Communication and Civic Education

KLUTSEY: Yes. I wanted to talk a little bit about platforms and technology. At the time, getting messages across, folks were using pamphlets and newspapers. Presidents and citizens used them as well. We have more sophisticated technologies now, from radio to podcast to Instagram, X or Twitter and Instagram and so on.

In your view, what’s the proper role of these technologies in conveying information, coordinating citizens’ actions and transmitting important information to strengthen democratic values? Garrison had The Liberator. Douglass had The North Star. Now we have lots and lots more. How should we be thinking about leveraging these tools and platforms?

BRETTSCHNEIDER: I think by analogy, sometimes there’s a worry. It’s a real worry, like, things are so different now. How could we look to the past? One thing that people say is media is so diffuse now, and it was so consolidated before. Now, it depends what point in history. That is true during Watergate, that many, many Americans watched the Watergate hearings. There were three networks, basically. There was consolidated media then.

But if you look way back, both to the editors and then (I love just to pick up on your examples) Garrison and Douglass’ papers, these were microconstituencies. They were polarized in the way that we’re polarized now in media. The technology is different, of course, but in many ways, the fragmentation actually is familiar. That can be a strength rather than a weakness because it can allow for organization and galvanization around these themes. Now, it comes with problems, too, but those problems were present then, problems of polarization and the like.

KLUTSEY: Yes, interesting. “We, the people” is a powerful concept and provides checks on the system when all else fails. How do we ensure that people are continuously aware of this power and can leverage it when necessary? Sometimes I worry that apathy is the thing that does us in. Is it via civic education of students? Is that where we can help to let people know how much power and strength they have in creating a check on the system?

BRETTSCHNEIDER: Yes. I think the lack of basic understanding of how the system works is one of the most important things that we need to fight against because it’s very hard to even understand how the traditional checks have failed—the argument of the book—and the role of “we, the people” in recovering the Constitution. These ideas, I think, for your listeners are familiar. For many Americans are not because we just have not been teaching all of this.

There’s a famous book about presidential rhetoric by Neustadt. In one of the editions—can’t remember the exact number, but he wrote several editions, and he has a preface for one of the subsequent from the original. He tells the following story: He says that some of the Nixon staffers were assigned the book, which is about how basically a president can use the bully pulpit to galvanize power. It was assigned reading.

The staffer says to him, “You’re responsible, too, for what happened,” meaning, “You wrote a book about power, and we took it seriously.” He’s taken aback by this because he says, “Look, when I was in school, we read Corwin and had this massive civic education at an early age. Of course, all of my recommendations about presidential power are meant to be within the bounds of the rule of law and the Constitution.” His point is, a lot of the assumption that civic education is always there—this is obviously in the early ’70s, he’s talking about—had disappeared already by then.

I think things have gotten worse, not better. It’s very hard for me to make even the arguments, to talk about the arguments that you and I are talking about, without civic education. I have written a previous book, and I’ll say a little bit more about how they compare, called “The Oath and the Office.” The subtitle is “A Guide to the Constitution for Future Presidents.” The idea of the book is, this is everything about the Constitution that you need to know if you want to be president of the United States. It’s written in the second person. As much as being written for presidents, it’s written for citizens to understand what these checks are, how they’re supposed to operate, how to think about the document.

Part of what this book is about is that those traditional checks, as important as they are and as much as we should bring them back, historically haven’t always worked. We’ve got to rethink the checks in a real way with actual examples throughout American history. The thing that has worked in the absence of these checks are American citizens demanding a reclamation of these core values that you and I keep talking about: the right to dissent, equal citizenship and the rule of law.

The Role of the Courts

KLUTSEY: Thank you. Given that the judiciary is often seen as a safeguard against the executive overreach, how do you see its role evolving? Can it remain an impartial check, or is it that it’s also one of these institutions that you have to keep an eye on and make sure that they are doing the right thing?

BRETTSCHNEIDER: Yes, it can’t just be that we trust the court, and whatever it says is the meaning of the Constitution. There is an unfortunate bipartisan view that seems to say that, this kind of Marbury v. Madison view that says judges interpret the law, the Constitution is the law—sometimes called the Marbury syllogism—judges have the right to interpret the Constitution. We know from American history that they very often, especially in moments of crisis, just get it really wrong.

Let’s go back. In the Sedition Act, Samuel Chase lobbies for the Sedition Act. He goes and sits at trial level to make sure that these editors are convicted. When they try to raise the free speech claims, he just doesn’t allow it. The idea that the Supreme Court is going to, in the way that we intuitively think the court is supposed to operate, strike down the Sedition Act as unconstitutional violation of free speech, no way. They are doing the extreme opposite.

Take the second example, Dred Scott. Did the Supreme Court come along and tell President Buchanan equal citizenship is required—of course, they’re standing for Dred Scott in this case, in his pursuit of his freedom? No, the court decides the case in conjunction with the president, with Buchanan, that says no rights at all for Black Americans. These are two of the most vicious assaults on democracy, not just by presidents, but with courts working alongside them.

KLUTSEY: I’d say that Korematsu v. U.S. is another major one, which fostered the internment of Japanese Americans and so on.

BRETTSCHNEIDER: Absolutely, Korematsu. The idea that America rounded up people based on race and ethnicity, and then the court not just upholds it, but lies, saying that this is somehow a security concern, even though they knew at the time there was no security concern about these families that were being rounded up.

Yes, the court just has a long history of getting it really wrong. Even in the best cases—there are counterexamples, U.S. v. Nixon is a classic one—if you look closely, they leave lots of room for the idea of immunity, even from prosecution, which we now see. That room has made a big difference.

Even Brown—and people might find this part of the book surprising, but part of the story that I want to tell is, look, Brown, of course, was an important case. Reversing Plessy v. Ferguson had a lot of symbolic and other value. In terms of what worked in desegregating America, it was Sadie Alexander’s insistence in the Truman Commission report that financial incentives be used to persuade, and then some public schools throughout America to desegregate.

The idea was that if you don’t desegregate, you’re going to lose federal funds. They’re providing the funds, on the one hand, but also not going to remove them if there’s not desegregation. That’s the idea of a citizen, of an economist. As important as Brown is in reversing the legal regime of Plessy v. Ferguson and the end of Reconstruction, it is the citizen action—more so, actually, in this case, than a court—that makes a difference.

Yes, it’s not going to be the courts. And it’s part of the civic education point, I think, that we can’t just let citizens defer to courts or think that reading opinions is how you figure out the meaning of the document. You have to think for yourselves and think about the principles and the values. That’s the Douglass legacy, too. Think about it the way he did.

KLUTSEY: Yes. Speaking of courts, the story about Chase being impeached is one of the most fascinating stories in the book—I guess the only judge who was impeached. It was attempted, but it didn’t actually succeed.

BRETTSCHNEIDER: It chastises them. An impeachment sometimes works that way. Even though it doesn’t succeed, there’s a reaction. He’s often described as partisan, and I think that doesn’t quite capture it. Of course, he was a partisan Federalist, but if that’s all he was, it wouldn’t be in a book about threats to democracy. It’s so much beyond that. It’s that he really worked with Adams to shut down the existence of the opposition party.

“Partisan” suggest that there are two parties, multiple parties, and they’re battling it out. That’s not what he was doing. They were working to eliminate the other party. The impeachment, I think, as much as people might say it’s Jefferson’s retaliation or something, no, it was essential to send the message that judges shouldn’t be playing that role. Of course, there are also pardons of all the people convicted under the Sedition Act. That’s also important, in addition to the refusal to bring it back.

The Call to Action

KLUTSEY: Yes. As we wrap up the conversation, I wanted to get your sense of what you think is the call to action from your book. If folks read the book, what do you want them to rally around, if you will?

BRETTSCHNEIDER: I’m often asked, who are the people that are going to do this in the future? The idea of the book certainly is that if we’re going to recover from what I think is the current crisis of democracy, it’s not going to be done by courts and not just by politicians, although a subsequent president might do it. It has to be at the behest of citizens.

And yet I’m reluctant to say, “Here are the 10 people: It should be Ben and Corey and eight others.” It’s really up to us. It’s a call to action. It’s up to us to be or find these people and organize and demand it. Certainly, one thing that I haven’t been shy about speaking out is—The Boston Globe said this isn’t so much history as prognostication. It’s future-predicting history because it came out the day after the immunity case. The idea that not just a sitting president but a former president is immune from prosecution, to my mind—you’ll see this in the book, that that’s one of the things, I think, that characterized the Nixon era that we have not yet recovered from and need to.

KLUTSEY: Corey, thank you so much for joining us. For listeners, the book is “The Presidents and the People: Five Leaders Who Threatened Democracy and the Citizens Who Fought To Defend It.” Really good book. Thank you for doing this.

BRETTSCHNEIDER: Thanks so much, Ben. Thanks for reading it so closely. I do a lot of interviews, and I really appreciate the details that you brought to this discussion. Thanks so much.