Packing the Court, Then and Now

By Charles Lipson

Not every war is won on the battlefield or ends with a surrender ceremony. Some are won quietly, sometimes before the killing starts, when the weaker side backs down because it expects to lose. The victory is achieved by intimidation and credible threats.

That is exactly what happened with Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s court-packing scheme in 1937. Unfortunately, the nature of his victory, and even the fact that he won, is widely misunderstood. Most commentators blathering on TV or the internet about current court-packing proposals actually think Roosevelt lost because he failed to add additional justices to the Supreme Court.

In fact, the president won because he got what he really cared about: acceptance of his major policy initiatives as constitutionally proper. The sitting justices listened to FDR’s threats, recognized his enormous political power after a sweeping election victory, and caved in. Then, one by one, the most conservative justices retired, allowing Roosevelt to reshape the court without adding to the existing nine members.

Why does Roosevelt’s victory still matter? For two reasons. First, it matters because progressives are trying to pack the court once again. And although their effort is unlikely to succeed (as they now realize), it is animated by the hope that, once again, the threat of court-packing will intimidate sitting justices, especially Chief Justice John Roberts, who has repeatedly shown he wants to avoid any conflict with the president or Congress. The recent clamor could also intimidate President Biden’s new judicial commission, pushing its members to recommend packing the lower courts. (More on that later.)

Second, it matters because Roosevelt’s court-packing episode was crucial to the reconfiguration of American politics, particularly the growth of the centralized state. That growth was only possible because the Supreme Court bent to Roosevelt’s demands and approved his regulatory programs. No issue is more important today. That is especially true now that the Biden administration is attempting yet another vast extension of federal power, the largest since President Lyndon B. Johnson in the mid-1960s.

Why the Standard Narrative About Roosevelt’s Court-Packing Is Wrong

The usual story about court-packing in the 1930s begins on the right track before jumping the rails and plunging into a ravine. We are told, accurately, that FDR was furious at the Supreme Court for blocking his most ambitious New Deal initiatives. “Unconstitutional”—that’s what the court ruled again and again about Roosevelt’s New Deal programs between 1933 and 1936. Led by Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes, the court struck down such fundamental initiatives as the National Industrial Recovery Act and the Agricultural Adjustment Act, as well as similar state laws, such as New York State setting a minimum wage and working conditions. Future proposals were sure to meet the same fate.

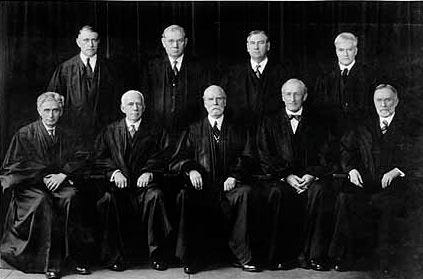

The Supreme Court in 1932, the year Franklin Roosevelt was first elected president. Image Credit: Smithsonian Institution

“It is running in the President’s mind that substantially all of the New Deal bills will be declared unconstitutional,” Roosevelt adviser Harold Ickes wrote in his diary. “This will mean that everything that this Administration has done of any moment will be nullified.”

To remove this obstruction, Roosevelt wanted to expand the number of justices. That was the basic political logic behind packing the court. FDR had just won an overwhelming victory in 1936 and carried a huge congressional majority with him. Now, he told the country, a court filled with “nine old men” stood athwart his efforts to drag us out of the Great Depression. Millions of people had voted for these much-needed programs, he said, and we must stop a few rigid, reactionary judges from blocking them.

Expanding the court was (and still is) possible because the U.S. Constitution does not fix the number of justices. There had been nine since the Civil War era, but that was merely a standard practice, a norm, not a constitutional requirement. In emergencies like the Great Depression, Roosevelt argued, we needed to abandon such harmful norms. That’s what he intended to do, and he had the wind at his back. Fresh off a huge electoral victory (523 electoral votes to 8), he was determined to push through his big federal programs. If he had to break some china to do it, get your brooms ready. Roosevelt’s arguments are eerily reminiscent of progressive ones today. We need action, not obstruction! Or so the political cry went.

This standard story about Roosevelt’s court-packing proposal is correct, so far. Where it goes off the rails is when it concludes that Roosevelt lost the battle over the courts. It is wrong, too, when it says the “loss” kept the court insulated from national political pressures. None of that is true.

FDR didn’t lose the contest over the Supreme Court. He won it, thanks to his public threats. True, it was a strange sort of victory. The public still admired the court, and normally enthusiastic Democrats in Congress refused to support Roosevelt’s attacks. They never passed a bill to expand the number of justices. Even so, FDR accomplished the one thing that really mattered to him. After his attacks, the court ruled in favor of every New Deal initiative on its docket, starting with the National Labor Relations Act (also known as the Wagner Act) and the Social Security Act, both path-breaking laws.

President Roosevelt in 1935, signing the Social Security Act into law. Image Credit: Library of Congress

In 1937, the court ruled both were constitutional. The court even handed Roosevelt victories that required the justices to ignore their own recent rulings. Take minimum wage laws. In 1936, they had ruled that New York’s minimum wage law was unconstitutional. One year later, they upheld a virtually identical law in Washington State. As the court’s abrupt move to the left became clear, its most conservative justices began to retire, defeated, beginning with Willis Van Devanter. Roosevelt would replace them with his own New Deal men.

With these victories, the president had removed the court’s blockage. He may have lost the congressional battle; he may have misjudged public opinion; but he had won the war. It was a monumental victory, one that would ultimately allow big-government liberals and progressives to reshape American government with judicial approval. And, as it became clear that the high court was no longer an impediment to their plans, they immediately began working to do just that.

The Consequences of Roosevelt’s Court-Packing Victory

Roosevelt’s judicial revolution has had lasting consequences, politically and legally. We live with them today, not as marginal features of our governance but as core elements. That’s why it is so important to understand what really happened in this court-packing episode and disperse the myths surrounding it.

The biggest change was to eliminate traditional constitutional limits on the central government’s expansion. Not only did Washington’s power steadily increase, dwarfing that of city and state governments, but so did the power of the president and his executive agencies within the national government. In short, quashing the conservative court opened the door to fundamental changes in American political structure, driven by Democrats and accepted by Republicans who typically governed within that now-accepted framework.

Roosevelt even got his new justices without expanding the court. The older justices retired, vanquished. The president replaced them with compliant jurists who gave all his programs a constitutional thumbs-up. That had been Roosevelt’s goal all along.

The popular narrative gets this political success and its long-term consequences wrong. Put differently, Roosevelt lost the skirmish to expand the court but won the much bigger struggle to ratify his New Deal initiatives as constitutional. His victory set the stage for massive government expansion ever since.

How a Few Bushels of Homegrown Wheat Changed American Government Forever

The clearest evidence of Roosevelt’s success came just five years after his ostensible defeat, in a case involving a trivial amount of wheat grown on a small Ohio farm. But the court’s decision had vast ramifications. The farmer, Roscoe Filburn, raised some animals and fed them with wheat he grew on the farm. He didn’t sell the wheat to anyone. (Occasionally, he sold other wheat, but not the wheat in question.) Yet the Roosevelt administration slapped him with a fine because his wheat production violated their rules, designed to keep grain production down and prices up.

The obvious question is, “What gave Washington the authority to regulate this homegrown wheat?” The Roosevelt administration’s answer was the constitutional clause regulating interstate commerce (Article I, Section 8, Clause 3). That clause gave Congress the power to “regulate Commerce with foreign nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes.” Filburn’s response was that his wheat didn’t involve commerce, much less interstate commerce. It was grown and consumed on his own farm and never entered the commercial market.

In its ruling in Wickard v. Filburn (1942), the court unanimously rejected the farmer’s argument. The reasoning in the court’s opinion wasn’t just tortured; it reached a level of sophistry that would have embarrassed the ancient Greeks. The justices began by saying that Filburn’s modest acreage shouldn’t be considered in isolation. No, it should be lumped together with all the wheat grown in America. “That [Filburn’s] own contribution to the demand for wheat may be trivial by itself is not enough to remove him from the scope of federal regulation where, as here, his contribution, taken together with that of many others similarly situated, is far from trivial.”

Moreover, the very fact that Filburn was growing his own wheat for his own consumption meant, by definition, that he wasn’t buying or selling it on the open market. By the court’s contorted logic, his grain was still interstate commerce because, if lots of farmers did the same thing, they would collectively affect America’s total supply and demand. Q.E.D. As the learned justices put it:

It can hardly be denied that a factor of such volume and variability as home-consumed wheat would have a substantial influence on price and market conditions. This may arise because being in marketable condition such wheat overhangs the market and if induced by rising prices tends to flow into the market and check price increases. But if we assume that it is never marketed, it supplies a need of the man who grew it which would otherwise be reflected by purchases in the open market. Home-grown wheat in this sense competes with wheat in commerce.

Get that? Wheat that is grown and consumed at home affects the interstate market in two important ways. First, it “overhangs” the market because it might be sold if the price were high enough. Second, even if it is never bought or sold, it changes the national market because (in modern language), all farmers taken together growing and consuming their own wheat would change the supply and demand curves. So, the court ruled, Filburn’s trivial amount of homegrown grain was interstate commerce and Washington had the constitutional authority to regulate it.

The Wickard decision effectively gave Washington the right to regulate nearly anything under the sun and soil, thanks to the Constitution’s interstate commerce clause. The dam holding back federal power had broken. Since then, an unending flood of federal regulations has gushed forth. Washington’s vast administrative state is built upon the Wickard ruling and many others like it. All of them are based on the Democrats’ political dominance of the Supreme Court, clinched in the wake of the 1937 court-packing threat. As for the Wickard decision itself, it still stands.

The court’s new orientation deeply eroded the country’s traditional emphasis on federalism and decentralized governance, as well as small businesses’ right to operate free from most federal intrusions. It demolished the country’s long-standing constraints on a large, strong and active central government.

This reorientation necessarily trampled the text and spirit of the 10th Amendment: “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states respectively, or to the people.” That amendment clearly defines a national government of limited and enumerated powers. It was never repealed, just ignored.

The Court, the Administrative State and the Washington Circle of Life

Overcoming these constitutional constraints wasn’t just the Roosevelt administration’s goal. It was embraced by his party and all its subsequent leaders. It has been the Democrats’ fixed objective for almost a century, perhaps longer since it can be traced to Woodrow Wilson’s progressivism.

And it wasn’t just one party’s objective. Since World War II, nearly all Republicans have governed within the same broad framework, tweaking it at the edges and tilting it toward their voters and benefactors instead of those of the Democrats. The only exceptions have been Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump, who challenged it directly.

The latest challenge began with the Tea Party, which germinated during the waning years of the George W. Bush administration and flowered during Barack Obama’s first term. Donald Trump built upon it, to the chagrin of traditional Republicans. It was his 2016 victory and energetic populist agenda that posed such a profound threat to the bipartisan, corporate consensus and its institutional structure.

Trump’s appointment of three conservative justices to the Supreme Court posed another serious threat. With a new, conservative majority, the court might undermine the constitutional underpinnings of the bureaucratic-regulatory state. That is still far from certain, both because the court is reluctant to overturn precedents and because justices don’t always rule the way their presidential patrons expect. Still, for the first time since the mid-1930s, changes on the high court could yield major changes in constitutional interpretation. That’s why the battles over Trump’s nominations were so brutal and why Democrats are still furious that Obama’s nominee, Merrick Garland, was denied a seat. That’s why progressives are so eager to pack the court now. The stakes are very high.

The most visible marker of those stakes is the size and prosperity of Washington itself. Once a small, sleepy town, it is now a sprawling, wealthy, immensely powerful behemoth. Almost every corporation and nonprofit has a major office there. That’s understandable. Every aspect of public and private life is affected by the policies made there. Think tanks and cable channels are spread across town, churning out justifications for their preferred policies. Retired lawmakers, who once returned home to play poker and swap stories with friends, now stay on as highly paid lobbyists. Former aides on Capitol Hill and White House and former officials in the bureaucracy do the same thing.

Washington is where the money is because that’s where the laws, rules and regulations are made. Those who work this system symbolize “the conduct of public affairs for private advantage,” as writer Ambrose Bierce once put it. Today, it could be called the Washington Circle of Life.

Current Proposals To Pack the Court

The Depression-era effort to pack the Supreme Court, which paved the way for big government, is the essential backdrop to current efforts to expand the court. Its leading proponents on Capitol Hill are Rep. Jerry Nadler (D-N.Y.), who chairs the House Judiciary Committee, and Sen. Ed Markey (D-Mass.). They have introduced legislation that would expand high court membership from nine to 13, and a slew of like-minded progressive organizations and donors back them.

Sen. Ed Markey (D-Mass.) on April 15, 2021, speaking at a press conference to introduce legislation to expand the number of justices on the Supreme Court. Image Credit: Drew Angerer/Getty Images

Their proposal fits snugly within the Democratic Party’s long political arc from FDR to LBJ to Obama. Each of these presidents has sought, successfully, to increase the size and scope of the central government and provide its ideological justification. Although Biden cannot match the eloquence of Roosevelt or Obama, he can at least try to complete Johnson’s Great Society and Obama’s health care expansion. And he is keen to do so, to make his mark, not with rhetoric but with massive, irreversible programs.

He faces one formidable obstacle, perhaps an insurmountable one. He simply doesn’t have the votes in Congress. Democrats hold a razor-thin edge in the House. The Senate is evenly split, 50-50. Democrats hold a nominal majority only because the vice president can break ties on most bills. That still leaves Senate Democrats (and the president) far short of the 60 votes needed to break a filibuster, which can block any legislation except budgetary items. The 50-50 split means Biden can ram through budget bills if all Democrats fall in line, but he can’t pass anything else without bipartisan compromises. And those are almost impossible in today’s bitterly divided climate.

The Senate Filibuster and Court-Packing

If the filibuster is blocking the president and congressional Democrats, why don’t they eliminate it? That could be done with a simple majority since it is a Senate rule change, not a law, and cannot be blocked by filibuster. Nearly all Democrats support it. The problem lies in that niggling phrase “nearly all.” To pass the rule change, every single Democrat would have to vote to kill the filibuster, and West Virginia’s Joe Manchin has repeatedly said he never will. He would likely be joined by Arizona’s Kyrsten Sinema. Both are relatively moderate, and both understand the rule change would transform the Senate into something very much like the House, where debate is irrelevant and party leaders control the agenda and outcomes. That’s very different from Senate tradition, where debate is important and members have considerable autonomy.

Even if the filibuster was eliminated, individual members can impede legislation and presidential appointments. They are understandably reluctant to surrender those privileges—and the power that comes with them. Beyond these procedural concerns, Manchin is surely aware that a Senate controlled by progressive Democrats and unchecked by the filibuster could pass bills on gun control, environmental regulation, religious liberty and social issues that are deeply unpopular in his state, which Trump carried by some 40 points.

This fight over the filibuster is directly related to court-packing because there is only one way to add members to the Supreme Court: pass a new law. It cannot be done by Executive Order. There’s no chance of passing such a law in today’s Senate, with the filibuster rule in place and 50 Republicans available to block it. The only way for Democrats to pack the court, then, is to eliminate the filibuster, and they simply don’t have the votes to do it. At least not now.

They don’t have the votes to secure a likely backup plan either. That plan, which has received very little public attention, would add more judges to lower federal courts. Several of those courts now have conservative majorities, and Democrats would dearly love to change that while they control the White House and Senate. Their public justification would be, “These courts are badly overworked. We need additional judges, not for partisan reasons, but to ease the burden and speed the judicial process.”

There’s a nugget of truth there, but there’s a big hunk of slag, too. Federal judges are, indeed, overburdened, and courts are painfully slow. But it is ludicrous to think any immediate expansion would be nonpartisan. In Washington today, the only things that aren’t partisan are milk, cookies and golden retrievers.

Still, Biden’s newly appointed commission on the federal judiciary could well recommend more judges for trial (district) and appellate (circuit) courts. The movement to pack the highest court ramps up the pressure on them to do so. Although the commission has some Republican members, it is packed with reliable Democrats. They might well propose expanding the lower courts while silently adding a partisan addendum: Let’s do it right now so Biden can nominate them and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer can get them approved. Senate Republicans would undoubtedly try to block this effort, seeing it as a partisan maneuver to seize control of the judiciary. Democrats would do the same thing if Republicans held the White House and Senate. Use your leverage while you can.

Is there a solution to overburdened lower courts? Perhaps. The key is to move slowly and methodically, spreading any new slots over several future administrations. Additional positions would become available each year, starting in 2025, and continue for the next three or four presidential terms. That would not change if a president was reelected. Since we don’t know which party would control future nominations and confirmations, this proposal wouldn’t be seen as a partisan power grab. Without such a compromise, the minority party will use the filibuster to block what it would see, rightly, as court-packing.

The only lingering question is whether justices on the current high court will be intimidated by these court-packing initiatives. The answer is only speculative, but it is likely that only the most politically sensitive will be. There are five strong conservative justices, plus a sixth, John Roberts, who often votes with the conservatives. Only Roberts is hypersensitive politically, perhaps because, as chief justice, he is the court’s institutional steward. The five conservatives are unlikely to be jolted by a toothless threat to pack the court.

What About the Politics?

Why float a proposal like Nadler’s and Markey’s that is sure to fail? Because it appeals to the party’s activist base. That may help incumbents such as Nadler fend off primary challengers from the left—a very real threat in deep blue states and districts like his. But it is beyond self-defeating for general elections in purple states.

The proposal is a boon for Republicans running for House and Senate seats. They would gladly buy advertising time to see Nadler on television in their districts. They are likely to retake the lower chamber anyway. The president’s party normally loses seats in the midterms, and the Democrats don’t have many to spare. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi understands the problem, which is why she won’t allow a floor vote on the court-packing bill. Since the bill is sure to die in the Senate, she must figure, “Why jeopardize any centrists in my caucus?” Still, she can’t protect them completely. Court-packing proposals by fellow Democrats have already gotten a lot of press and are likely to hurt the party in the next election.

Republicans face a more difficult electoral challenge in the Senate. By the luck of the draw, more incumbent Republicans than Democrats face the voters in 2022. But if court-packing stays in the news and isn’t suppressed by tech barons and their “woke” lackeys who control social media, it will help Republicans in a couple of ways. First, it is deeply unpopular with average voters. Second, it allows Republicans to highlight one of their strongest electoral arguments: It is dangerous to allow one party to consolidate power in both Congress and the White House. Remember the wisdom of our Constitution, with its separation of powers.

The Founders believed that the best insurance against tyranny was to separate sovereign powers among several branches, each with good reasons to preserve its authority and prevent encroachment by the other branches. That is why James Madison, borrowing from the Baron de Montesquieu, made this separation of powers the fulcrum of the Constitution.

In Federalist 51, Madison explained the basic problem: “The great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.” In their effort to ensure that the government “control itself,” the Founders relied on the separation of powers. They also appended a Bill of Rights, limiting some areas from government encroachment, but that is only a paper barrier, albeit a revered one, and is not self-enforcing. That’s why they considered the separation of powers crucial.

This institutional design was unique—and brilliant. The Founders divided sovereign power among three branches and divided the legislature itself in two, with different electoral rules. The idea was that each branch would have strong reasons to maintain its power and institutional autonomy. The goal was to prevent the consolidation of unfettered power in one person or body.

The Democrats’ proposal to end the filibuster and pack the courts highlights this “separation of powers” argument. The argument carries even more weight because the Democrats are openly seeking to eliminate minority power in the Senate and then use their temporarily inflated power to:

Lock in long-term control of the Senate by adding new, reliably Democratic states (the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico) to the Union,

Federalize election laws (via HR 1), which are normally set by each state, but which Congress may alter (Article I, section 4), and

Seize control of the third branch of government, the judiciary, by flooding it with Democratic judges.

Some Democrats have openly proclaimed these grandiose goals, hoping to push through whatever they can before 2022, when they might lose control of the House. If they succeed, they will control all three branches, as well as the rules for future elections. Other, wiser heads in their party share the same goals but are shrewd enough to maintain radio silence. Loose lips sink ships.

They could sink this one. The voters don’t like expanding the Supreme Court. Not one bit. In the latest polls, just 38% say they favor adding four new justices. Voters see these maneuvers, quite rightly, as a naked power grab that would fundamentally undermine the separation of powers and, with it, the Constitution’s basic structure and its institutional protections against tyrannical rule. They see a political party trying to accomplish this transformation with the thinnest of electoral margins, one that may very well disappear soon.

Progressive Democrats aren’t just overreaching here. They’ve grabbed a hammer and started breaking bones. Unfortunately for them, those bones are their own. Unfortunately for us, they are ours, too.