Once Upon a Time in ‘The West’

The ‘Culture War Christians’ denigrate the pre-Christian roots of Western civilization

I’ve been writing recently about how we can live without religion as America becomes a more secular society—frantic attempts to reverse that trend notwithstanding. I’ve addressed this objection on the personal level, how we can find secular sources of meaning, purpose and love in our own lives. But the same objection is brought up on a larger scale.

Where some cannot imagine a personal alternative to religious belief, others cannot imagine a civilizational alternative. Hence the rise of “Culture War Christians,” right-leaning intellectuals who can’t necessarily bring themselves to affirm the truth of traditional religious beliefs on an intellectual level, but who argue that such beliefs are nonetheless necessary as an answer to various threats and challenges. This argument has become increasingly prominent among supposedly “heterodox” thinkers on the right—who are now becoming more and more orthodox in the original sense.

But they are deeply underrating the actual intellectual and spiritual strength of our civilization, and what is worse, they are selectively ignoring or denigrating its deepest and earliest roots. They want to defend “the West” without really acknowledging what it is.

The Culture War Christians

Perhaps the most famous of these new culture war converts is former atheist Ayaan Hirsi Ali, who wrote about becoming convinced that Western civilization was “built on the Judeo-Christian tradition.”

[F]reedom of conscience and speech is perhaps the greatest benefit of Western civilization. It does not come naturally to man. It is the product of centuries of debate within Jewish and Christian communities. It was these debates that advanced science and reason, diminished cruelty, suppressed superstitions, and built institutions to order and protect life, while guaranteeing freedom to as many people as possible.

If there was anything else at the basis of these achievements, she does not seem to be aware of it.

In Persuasion, Matt Johnson provides part of the rejoinder to this, pointing to the roots of our distinctively Western ideals and political system in the skepticism and empiricism of the Enlightenment, ideas that were deeply at odds with Christianity.

While there were gradations of belief and unbelief among Enlightenment thinkers, a core aspect of Enlightenment thought was criticism of religion. And no wonder: the Enlightenment was in large part a response to centuries of religious oppression, dogma, and violence in Europe.

But the answer is bigger and older and goes back to the root of the whole idea of “the West” itself—which, it turns out, predates the “Judeo-Christian tradition” by half a millennium.

Once Upon a Time in the West

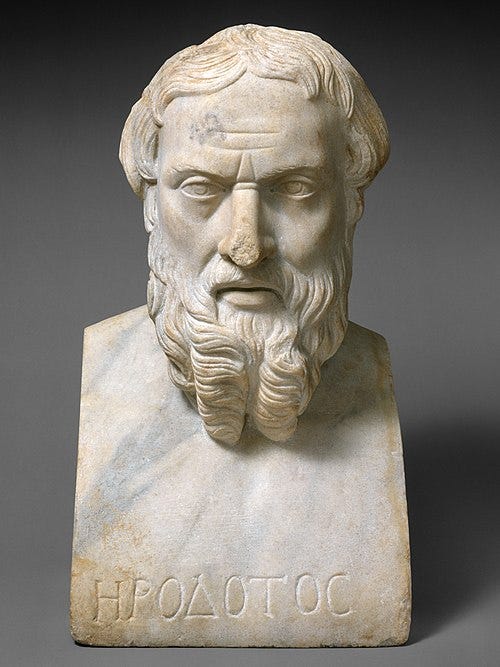

The idea of “the West” as a distinct entity that is politically and culturally different from “the East” has a specific intellectual birthplace. It was first invoked by the Greek historian Herodotus. In his “Histories,” written about 430 B.C., he used this as a framework for the bloody conflicts in the fifth century between the independent Greek city-states and the Persian Empire. This contained the germ of the ideas that the West is rational while the East is superstitious, and that the West values freedom while the East accepts the yoke of despotism.

But Herodotus wasn’t just writing about the distinctive culture of the West; he also embodied it. He was part of an explosion of intellectual creativity in ancient Greece that invented virtually all of the sciences as we know them. (Herodotus’ writings are considered the first step toward the scientific history of Thucydides.) “Western civilization” has become something of an anachronistic term, since in our era it has become a truly global scientific and technological civilization, providing the core of modernity that has transformed the world. But it did begin in “the West” as Herodotus knew it, with the earliest Greek scientists and philosophers.

Between 600 and 500 B.C., Thales and Anaximander were the first to use natural causes to explain the world. Every culture has had myths and legends in which the origin of the universe and the actions of objects are attributed to the intervention of gods or spirits. The birth of Greek philosophy—and along with it, the foundations of a scientific outlook—started with the replacement of mythology with the study of natural causes.

The physicist Carlo Rovelli argues that the next important development came with Thales’ successor Anaximander, because he was the first student who disagreed with his master—setting another distinctively Western precedent of constant questioning and a quest, not just to preserve what came before, but to progress beyond it.

Meanwhile, at about this time—circa 600 B.C.—in what Herodotus would have regarded as “the East,” the Old Testament was still being compiled from competing Jewish oral traditions. So the whole origin of “the West”—as an idea and as a distinctive philosophy and way of life—came five centuries before Christ and before the Old Testament was widely known outside Israel, and it specifically began as a secular alternative to religious explanations and appeals to authority.

What Has Jerusalem To Do With Athens?

The most curious part about this debate is that those who insist on a Judeo-Christian origin for Western civilization are ignoring key parts of their own religious history. Christianity first spread in the classical West—ancient Greece and Rome—and began a 2,000-year-long struggle with Greek philosophy and classical ideals, alternately attempting to banish them and to reconcile with them, to the point where Christianity itself can now hardly be imagined without elements of the pre-Christian West.

Don’t take my word for it. Years ago, Pope Benedict XVI gave a controversial speech that was nominally about the relationship between Christianity and Islam—hence the controversy—but was really about the relationship between faith and reason. This included his celebration of the “Hellenization” of Christianity, its transformation by its connection with Greek philosophy.

This inner rapprochement between Biblical faith and Greek philosophical inquiry was an event of decisive importance not only from the standpoint of the history of religions, but also from that of world history—it is an event which concerns us even today. Given this convergence, it is not surprising that Christianity, despite its origins and some significant developments in the East, finally took on its historically decisive character in Europe. We can also express this the other way around: this convergence, with the subsequent addition of the Roman heritage, created Europe and remains the foundation of what can rightly be called Europe.

Pope Benedict agrees with me—and not with the New Theists—in regarding the Greco-Roman tradition as an indispensable starting point for Western civilization that even the Judeo-Christian tradition can’t do without.

The Old Republic

The real question is what these pre-Christian sources have to offer on the big questions. In my previous article, I addressed two of the concerns for which Christianity is supposedly needed in our personal lives—the fear of death and the need for love—that were also addressed by pre-Christian classical thinkers.

Similarly, the Culture War Christians look to Christianity as the foundation for the idea of political equality, finding it in Paul’s exhortation: “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus.”

But the idea of political equality was already widely discussed in the classical world, particularly among the Romans. Prior to Christ, the historian Livy and the great republican champion Cicero had written about “equality of rights before the law” being at the heart of the Roman system. The Greeks and Romans were already developing a distinctive basis for Western ideals and institutions of political equality, one that they put more fully and directly into practice than any system before—and up until the Enlightenment. These advances were limited, of course, tending to apply only to citizens and not universally—but one can say the same thing, in practice, about the Christian tradition, which has cohabited for centuries with various forms of serfdom and chattel slavery.

More broadly, the classical world developed the first democracies and republics at about the same time they were creating the sciences. The Romans overthrew their king and vowed not to have another one in 509 B.C.; Cleisthenes established Athenian democracy in 507. Even earlier, if you read the works of Homer, you will already find the habitual practice of making decisions by deliberation in an assembly. It is no coincidence that the classical world also developed the first traditions of free inquiry and debate. The Greeks had a word for it, parrhesia, directly translated as “say everything.” The Athenians in particular considered it not just a prerogative but a crucial virtue to speak one’s mind frankly and without fear.

Both these traditions, political representation and free inquiry, were suppressed for centuries after Christianity became dominant in the West, and they did not really recover until the revival of the classical tradition in the late Middle Ages. So to claim that Christianity is the only or the primary foundation for Western civilization is to ignore much of the actual history of the West and much of the substance of the tradition these Culture War Christians claim they want to defend.

A Traveler From an Antique Land

My background makes it easier for me to see this. I sought out secular alternatives for spiritual meaning, not because I preferred them, but because I found no other choice. I was simply unconvinced of the truth of the religious answers, and if those weren’t the real answers, I figured I’d better start looking for others. Not only did I find alternatives, I found them to be rich, abundant and—some, but not all—well-grounded in observable fact.

Our culture as a whole is beginning this same process, as a scientific worldview makes a literal belief in the old religious mythologies harder to maintain. We’re at a tipping point now where the growth of nonbelievers, from a tiny sliver to a substantial minority, erodes the social presumption in favor of faith. It’s starting to become OK not to believe.

But there is a lot of anxiety, even panic, that there will be no alternative. Hence the rise of the Culture War Christians trying to find a way to maintain the supposed advantages of faith without the substance of it.

Those of us who have journeyed on ahead of you into the universe of secular meaning are here to reassure you. You might still find religious or Christian answers more personally satisfying, but you will eventually come to recognize that these are not the only answers and certainly not the first.