Liberalism After the Insurrection

The lack of ideas has consequences

What we saw on Wednesday in Washington was a physical assault against the institutions of the American republic, full stop, and one that comes after years of increasingly normalized political violence. Historical parallels, both within our own country and abroad, all seem inapt; what we are witnessing is in fact sui generis.

How we got to this point will take weeks for law enforcement to unravel and years for historians to analyze. But both Wednesday’s insurrection and the larger climate of political violence, intimidation and destruction that has in recent years become accepted and even encouraged, including by swaths of elite opinion, stem in large part from a diminishment in the role of ideas, words and values in our public discourse.

It was not that long ago that the primacy of ideas was seen as self-evident across the political spectrum. Ideas Have Consequences was the title of Richard Weaver’s 1948 conservative critique of modernity. John Maynard Keynes wrote, “Practical men who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.” This sentiment was echoed a generation later by Paul Samuelson, who quipped, “I don’t care who writes a nation’s laws . . . if I can write its economics textbooks.” A generation of young Republicans came to Washington wearing Adam Smith neckties and quoting Friedrich Hayek. No self-respecting socialist apologist would turn down a chance to “discuss theory.”

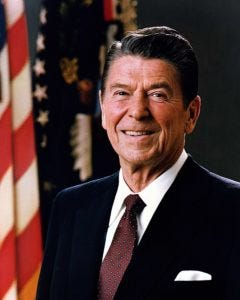

Four months after his 1984 reelection, President Ronald Reagan spoke to an audience at the Conservative Political Action Conference, attributing his landslide victory to the power of ideas:

The tide of history is moving irresistibly in our direction. Why? Because the other side is virtually bankrupt of ideas. It has nothing more to say, nothing to add to the debate. It has spent its intellectual capital, such as it was—[laughter]—and it has done its deeds. . . .

We in this room are not simply profiting from their bankruptcy; we are where we are because we’re winning the contest of ideas. In fact, in the past decade, all of a sudden, quietly, mysteriously, the Republican Party has become the party of ideas.

It’s impossible to imagine an American politician saying this now. Today, ideas are far from the animating force of politics. Indeed, it’s hard to name a single original or even newly refreshed idea that animated the 2020 election.

On the right, the only real question was personal fealty to President Trump. Recall that the GOP platform was simply a one-page resolution that recited grievances against the media and proclaimed allegiance to the president. Democrats were content mostly to push to expand existing spending and entitlement programs while embracing illiberal ideas of racial essentialism and ahistorical revisionism.

Ideas still matter, of course, and there’s no shortage of them coming from academics, think tanks, journalists, pressure groups, unions, business lobbies and more. It’s just that these ideas are not what animate citizens and their public servants.

We’ve seen a similar debasement in the power of words. In the 1990s, Republicans and late-night talk show hosts were afflicted by paroxysms of heartburn and howls, respectively, over President Bill Clinton’s under-oath exegesis on the third-person singular present-tense form of “to be.”

It’s now an article of faith among much of the left that “hate speech” is not constitutionally protected and that words are violence—while at the same time slogans such as “defund the police” don't really mean what they say, and anyone who suggests they do is acting in bad faith. This summer, many ostensibly serious intellectuals of the left beclowned themselves comparing self-described antifascist activists (fact check: they were hard-left authoritarian rioters assaulting police, intimidating civilians and destroying property) to the men who stormed Normandy, defeated the Axis powers and liberated the concentration camps because both, after all, were against “fascism,” as if that word meant nothing.

Meanwhile, Trump’s defenders have spent four years telling us to ignore the words spoken or tweeted from the bully pulpit, to the point where the president’s lawyer could call for “trial by combat” as the pinnacle of a two-month campaign to elide the difference between allegation and evidence that has caused tens of millions to believe that which simply is not so.

This bipartisan postmodernism is straight out of Lewis Carroll: “The question is,” Alice asked Humpty Dumpty, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.” To which the egg replied, “The question is, which is to be master—that’s all.”

Which brings us to values. The left and right were long animated by values briefly summarized, respectively, as defense of the downtrodden and marginalized, and ordered liberty as the highest good for both its own sake and its attendant material benefits. Both sides subscribed, in the main, to rules of the game that characterized the liberal order, among those being respect for fair play, the primacy of reason and at least a tenuous respect for the truth.

There were exceptions to these values, of course, such as the segregationist Southern Democrats and the conspiratorial fringe of the Republican hard right. But these exceptions prove the rule: both factions were undone by the members of their own movements who read them out of meeting with explicit appeals to better values.

Common liberal values have been replaced by common illiberalism, best exemplified by the illiberal right’s pleasure in “owning the libs.” Less than a decade ago, Tea Party activists took pride in cleaning up after their rallies and respecting police officers. Progressives, bearing the mantle of the civil rights movement, stressed nonviolence, peace and respect for private and public property as they marched against the Iraq War and for social justice.

For years, “facts don’t care about your feelings” was the conservative taunt of what they saw as mushy-headed progressives. Almost overnight, facts were replaced with conspiratorial fantasies. (The same thing happened on the left, of course, except it was Trump at the center of every conspiracy.) This is all made possible by the epistemic closure brought about by the ability to never read views other than the ones you share, even when those views posit that a ring of satanic pedophile cannibals secretly runs the world.

None of this is to look through to the past through rose-tinted glasses. After all, politics is ultimately an exercise in power, and politicians telling half-truths and checking the wind with a wetted finger is the natural order of things. But for much of the 20th century, it was the case that prevarications and breaches of commitments would be held within certain parameters, and politicians would see at least some repercussions for their actions. You could fib, you could stretch the truth, you could spin—but you couldn’t invent things from whole cloth.

Even Richard Nixon, a man whose name would go on to become synonymous with paranoia, scandal, dissembling and public shame was constrained by grudging respect for American political institutions and social strictures of decency after his loss to John F. Kennedy in 1960—an election that was, in fact, possibly stolen. And 14 years later when his betters informed him, for the sake of the country, that he needed to leave the White House, he resigned.

The assumptions of decency that even Nixon managed to meet are no longer operative in American public life. This is the crisis of liberalism we face today: where institutions have been denuded of ideas and values, and where the words of ostensible statesmen and leaders have become as worthless as Venezuelan currency. As Martin Gurri has shown, there’s no putting the genie back in the bottle, at least any time soon.

So, what comes next? I have no good answers. Perhaps people will look at the storming of the Capitol, an act of nihilistic negation done under the most transparently false of pretenses, after a summer of sporadic rioting that did billions of dollars in damage and years of organized street terrorism by groups we were told don’t exist, and once again realize that ideas have consequences, words matter and values must be binding, not optional, constraints.

Perhaps a new crop of politicians who take ideas seriously and possess some limits to their mendacity will emerge, aided by political institutions that are, in Yuval Levin’s excellent phrase, “molds of character and behavior [rather than] platforms for performance and prominence.” Perhaps we’ll put politics back in its rightful place and step back from the politicization of everything.

At this moment, however, all we can do is stand up individually and tell the vandals of all political hues: No. Stop this. It’s gone too far. Stop rationalizing it, defending it, minimizing it. It’s not a game. Wednesday’s melee resulted in the death of one police officer and injuries to dozens more. Four rioters are dead. Businesses across the country have been torched, with their owners, employees and customers left holding the bag. People have been shot and stabbed. This isn’t live-action role-playing; it’s real life.

Ours is a time for choosing. As individuals, and as institutions, we have to choose a path—and we either have to disassociate from those who would through foolishness or cynicism lie to their readers, their voters and the public to achieve either personal advancement or parochial goals, or we’ll be sullied by and sucked into their nihilistic void. Liberalism is worth defending, especially from those who would destroy it for the worst possible reasons.