Juneteenth Is as American as Apple Pie

The holiday reminds us of the many ways Black Americans have contributed to the national culture

By Rachel S. Ferguson

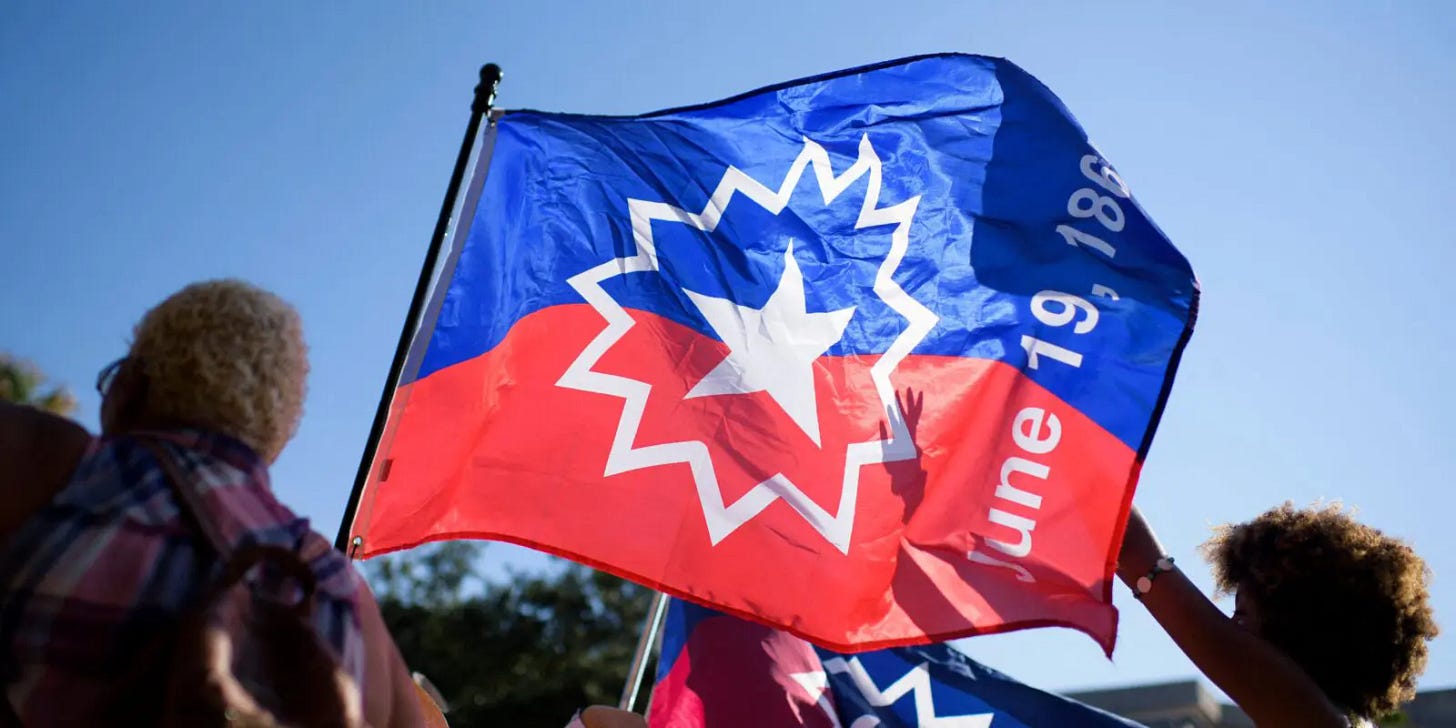

A minor debate rages in the media sphere over what flag should be used at Juneteenth festivities. A Juneteenth flag was first introduced about 25 years ago. On this flag, a red horizon rises to a blue field, with a white star surrounded by a starburst in the center. But as the profile of Juneteenth has risen, some have thrown together other images using the pan-African colors popularized by Marcus Garvey. The argument about which flag to use is instructive: It illustrates the difference between two common understandings of Juneteenth’s significance.

The historical Juneteenth flag deliberately adopts the colors of America: red, white and blue. The star nods to Texas, the Lone Star State and the last one where the news of genuine emancipation finally reached formerly enslaved people. The curved horizon and the starburst indicate something new, exciting and aspirational for those freed from slavery. (Later, the relevant date—June 19, 1865—was added as well.) Garvey’s pan-African colors (yellow, green, red and black) have become a commonplace indicator of Black identity, so it’s no surprise that some would combine the two concepts. But to many participants, it’s important to maintain Juneteenth as a distinctly American holiday because their shared experiences have created a distinctive Black American culture.

Seeing Juneteenth as an American holiday doesn’t mean rejecting another, broader concern for all those who originate on the African continent. While Africa is the most diverse continent in terms of ethnicity, language and religion, there are certain mainstays of pan-African culture—in dress, dance and storytelling, for instance. Africans have also shared in the devastation of the slave trade—first the Arabic one in East Africa, which took primarily females, and then the European one in West Africa, which took mostly males—with indescribably awful social and economic effects. But for Juneteenth, the descendants of American freedmen and freedwomen want to hold onto the specificity of their particular experience as a people finally allowed to enjoy the blessings of a place that was, otherwise, uniquely free.

We live in puzzling times. As someone familiar with the history of conservative thought, I’ve been baffled to observe the reaction of some conservatives to the rise of Juneteenth. When then-president of the Heritage Foundation, Kay C. James, tweeted out a lovely essay about her family’s celebration from her childhood (James grew up in Texas), the majority of comments accused the Heritage Foundation—yes, the Heritage Foundation—of “going woke.”

The conservatism with which I am familiar, of men like Edmund Burke or Russell Kirk, deeply values the cultural traditions and customs that empower people to flourish in their lives together. Reflective conservatives, as Kirk calls them, may be individualists in the legal sense of the term, but they have a profound appreciation for those institutions that form healthy individuals: the family, the church and the community—in short, civil society. It is within these havens of common life that we search for truth, create and enjoy beauty, and pursue the good.

Yet, when discussing Black culture, Black concerns and even the Black church, I am often asked why we still have to talk about Black and white. Those participating in such conversations are accused of hypocrisy; after all, would we be commended for celebrating white culture, worrying about white concerns or referring to an entity called the white church? And why am I capitalizing Black but not white? I’ll tell you! I don’t capitalize black when referring to skin color. I also don’t capitalize black when referring to Africans. It just so happens, as an accident of American history, that a subculture formed because people of African descent were segregated by skin color and thus came to be called Black. Just as I would capitalize Irish American, then, I capitalize Black to denote a specific American subculture.

Much of this subculture is drawn from its geographic location in the South (90% of Black Americans lived in the South until 1940). But much of it is also drawn from the unique experiences of Black Americans in both the South and the North, such as the formation of (necessarily, at the time) separate churches, which led to the flourishing of Black gospel music, the whooping style of preaching and ecstatic worship.

The descendants of formerly enslaved people started schools that brought Black America to 80% literacy by 1930. They formed the National Negro Business League and gave rise to the likes of Annie Malone and Madam C.J. Walker, both of whom are claimed to be the first female millionaire (and not just Black female millionaire). They started mutual aid societies and fraternal orders such as the Black Elks. Their music blossomed into blues, rock, soul, jazz and hip-hop. They organized the civil rights movement and promoted a philosophy of nonviolent political action that inspired the world.

Am I saying that there is no comparable white culture deserving of a capital ‘W’? In fact, yes. Whites were far too geographically spread out across the U.S. to form such a specific set of institutions or to share such a unique set of historical experiences. Culture is primarily geographic, or at least, it was until the rise of the internet. Whiteness, then, refers to a legal category—to which it was quite advantageous to belong—but nothing more (Smithsonian worksheets notwithstanding). Poor Appalachians have very little in common with the Northeastern descendants of Puritans, who have even less in common with the descendants of Western pioneers.

Surely there are certain American cultural distinctions, such as our tolerance for risk-taking and a certain penchant for innovation. I’ve also heard that people overseas find us to be quite loud. But these are not specifically white characteristics, as they are shared by all Americans, and America has been a multi-ethnic republic from the very beginning.

The essence of America has always been freedom. The freedom to worship attracted nonconforming religious sects to America. Thomas Jefferson enshrined the belief in freedom in the Declaration of Independence, inspiring revolutions against tyrannical governments around the world. The freedom to trade attracted the most hardworking and innovative immigrant communities here. But the one group most horrifically and consistently denied inclusion in America’s dream of freedom was Black Americans. Because they were enslaved, criminalized, persecuted and segregated, Black Americans’ dream of freedom was far too long in the making.

Even though the end of slavery did not bring full participation in the body politic, it was the harbinger of things to come. Juneteenth is truly our second Fourth of July. It’s the declaration of freedom, not just for some but for all. There’s nothing more American than that.