John Varley: An Appreciation

For five decades, the American science fiction writer has offered readers a unique blend of imagination and realism. He deserves a wider audience

It was 50 years ago this month that American science fiction writer John Varley—who celebrates his 77th birthday today—published his first short story. It sparked a rapid rise that brought him the praise of the genre’s most prominent figures, along with multiple Hugo and Nebula awards (the science fiction equivalent of the Pulitzer). Isaac Asimov was among the many who called him the natural successor to Robert A. Heinlein.

Yet despite the immense admiration Varley has enjoyed both within the science fiction community and without (Tom Clancy called him “the best writer in America”), he has never gained the following that Asimov or Heinlein enjoyed. That’s a shame because his unique blend of imagination and realism—and his underlying belief that freedom is essential to the human personality—make him one of the finest authors ever to set his fiction in the future.

Stranger in a Strange Land

Raised in an obscure Texas town called Port Arthur, Varley fell in love with science fiction when his junior high school librarian gave him a copy of “Red Planet,” one of Heinlein’s famous “juvenile” (young adult) novels he wrote to introduce teens to space exploration. After high school, he moved north to study physics at Michigan State, but dropped out, preferring the life of a San Francisco hippie instead. It was while living in a Haight-Ashbury apartment that he decided to try writing for money, and the hippie element has played an important role in his fiction ever since—not (or not usually) in the sense of “tune in, turn on, drop out,” but of rebellion, self-reliance, hard work and creativity that remain underappreciated elements of the ’60s counterculture.

Contrary to the popular stereotype of hippies as drugged-out, unemployed hitchhikers, many members of the Woodstock generation (Varley attended Woodstock, by accident, after getting stuck in the traffic jam while driving through New York) put a heavy emphasis on manual trades, intellectual innovation and self-improvement. Many members of the counterculture weren’t anti-capitalist per se, but were committed to what historian David Farber calls “right livelihood”: that is, a life of genuineness not offered by what they called “the Establishment.”

It’s that element of ’60s youth culture—one which owes more to Ralph Waldo Emerson than to Timothy Leary—that forms the framework for many of Varley’s tales. Take his first published story, 1974’s “Picnic on Nearside.” It features two friends—Fox and Halo—who live on the moon in the distant future, after Earth has been invaded by aliens who render it uninhabitable. After Halo has a quick sex-change to become female, the couple takes a trip to the side of the moon from which Earth can be seen—a side most humans now avoid because it makes them remember everything they’ve lost.

Along the way, Fox and Halo happen upon a solitary hermit named Lester, the lone practitioner of an ancient religion called Christianity. They’re puzzled by his idiosyncratic beliefs—his objections to their casual sex, for example, and his refusal to employ the genetic technology that would keep him alive past his four-score-and-twenty years—but by the end of the story, Fox and Halo have gained a degree of respect for him, along with a better understanding of themselves, in terms clearly influenced by the way the ’60s generation saw their parents. “He was inarguably a fool,” Fox reflects. “A fool with dignity, and the strength of his convictions… but a fool all the same…. He couldn’t bear to see the Nearside abandoned out of fear, and he feared the new human society. So he became a hermit. I want to go there simply because the fear is gone for my generation…. We’ll be the vanguard.”

“Picnic” became the first in a group of stories set in a shared universe called the “Eight Worlds,” in which humans, now refugees from the invasion, live in shelters on the moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars and the satellites of Saturn and Jupiter. Many people live in cleverly constructed underground facsimiles of Earthside locales called “disneylands” (the Texas disneyland, the Kansas disneyland, etc.). The challenge of survival is made easier by new technologies, including a technique for memory-recording that lets people store their personalities as a form of insurance against fatal accidents.

In “Overdrawn at the Memory Bank” (1976), the main character uses memory-recording technology to go on a sort of vacation: putting his mind into the body of a lion on the savannah of the Kenya disneyland. Things go awry, and he finds himself trapped inside a computer while technicians try to figure out a way to reinstall him in a cloned body. In “The Phantom of Kansas” (1976), the main character is a type of artist called an Environmentalist, whose medium of expression is weather: She creates storms inside the disneylands by manipulating the weather-making equipment. Unfortunately, she keeps being murdered, only to be reawakened from stored memories. Meanwhile, the cops can’t find the culprit.

Self-Reliance

As these examples suggest, Varley’s fiction is marked by radical inventiveness, yet the qualities that make his work truly extraordinary are the smoothness of his prose and the realism of his characters. Together, these suspend the reader’s disbelief even through the strangest premises, in a manner that indeed resembles Heinlein, but without Heinlein’s distracting penchant for preaching about his political and social fixations. Actually, Varley’s writing more resembles that of hard-boiled detective writers like Donald Westlake: Witness his story “The Barbie Murders” (1978), in which detective Anna-Louise Bach pursues a killer who’s a member of a cult obsessed with eradicating all individuality. Since the sect’s acolytes (nicknamed “barbies”) reconstruct their bodies to be genetically indistinguishable, Bach’s efforts to finger the murderer are virtually hopeless. But as outlandish as the setup may be, Varley handles the story like a skilled mystery author:

People were moving more swiftly now, and a scuffle had developed ahead of her. She struggled free of people who were breathing panic from every pore, until she stood in a clear space. The speaker was shouting to be heard over the sound of whimpering and the shuffling of bare feet. Bach moved forward, swinging her outstretched hands. But another had brushed her first. The punch was not centered on her stomach, but it drove the air from her lungs and sent her sprawling. Someone tripped over her, and she realized things would get pretty bad if she didn’t get to her feet. She was struggling to get up when the lights came back on. There was a mass sigh of relief as each barbie examined her neighbor. Bach half expected another body to be found, but that didn’t seem to be the case. The killer had vanished again.

It’s easy to see the parallels between Varley and Heinlein, to whom he’s so often compared —especially between the former’s shared “Eight Worlds” universe and the latter’s “Future History” series of stories, all of which also are set in a shared universe. Parallels also exist in the self-reliant pragmatism and entrepreneurialism of both writers’ characters. Yet Heinlein was convinced of the necessity for nationalism and even militarism (his famous 1959 novel “Starship Troopers” has even been called “fascist” for its emphasis on these themes), whereas Varley, who successfully avoided the draft during Vietnam, has never showed sympathy with such views. His characters are too firmly committed to freedom to imagine that it can ever be defended through conscription.

When the characters in one of his novels become the first people to land on Mars, they choose not to raise an American flag, because their mission isn’t government-sponsored; or a U.N. flag, because they don’t put much truck in the U.N.; or the flag of their home state, because (says one) “I wouldn’t trust those idiots in Tallahassee to run a mud puddle, much less a planet.” So they end up raising no flag at all. The characters in “Starship Troopers” would never have done that.

Another aspect of Varley’s writing that differs from Heinlein’s is his emphasis on women. In the late ’70s and early ’80s, science fiction writers began pushing toward greater realism and philosophical sophistication in their work, and this so-called New Wave was especially influenced by 1960s feminism. Varley’s work fit right in, given the prominent roles played by his female characters. His stories were often told in the first-person by women narrators, and because one premise of the “Eight Worlds” was that characters could easily change sex, his stories also frequently explored the drastic consequences gender-switching would have on families—particularly in 1979’s “Options,” in which a wife decides to become a man. What makes that story succeed is precisely the fact that Varley doesn’t lecture readers but simply dramatizes the understandable tensions and questions that this raises within the marriage.

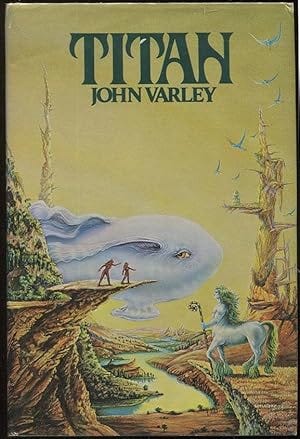

A female main character also dominates what would become Varley’s greatest work: the “Gaea” trilogy (Titan (1979), Wizard (1980), and Demon (1984)), in which astronaut Cirocco Jones and her crew encounter an alien world run by an intelligent supercomputer who calls herself Gaea. Gaea is effectively a goddess; she uses genetic engineering and other technologies to oversee all the fantastic lifeforms inhabiting her world—from centaur-like Titanides to Blimps (flying whales whose bodies secrete buoyant hydrogen) to the trees that grow pre-segmented into two-by-four strips so they shatter into lumber when felled.

But it turns out Gaea is not benevolent, or even sane, and over the three novels, Jones and her friends must find a way to liberate the oppressed Titanides from her increasingly despotic rule. Jones is the ultimate Varley character: skeptical, self-reliant, and as hard-nosed as a film noir detective, yet ultimately vulnerable and idealistic. She is not ideological, but defiantly committed to an intuitive sense of justice. These are the qualities needed to overthrow an insane god.

Going Hollywood

Superb as these stories are, it was 1977’s “Air Raid” that changed the course of Varley’s career. A tale about time travelers who rescue passengers from crashing airplanes in order to repopulate a distant future in which humanity can no longer reproduce, “Air Raid” quickly caught Hollywood’s attention. Varley—who’s been nuts about movies all his life—soon found himself in a studio office, working to transform his story into a screenplay and a novel. The usual Tinseltown delays intervened, and “Millennium” wasn’t released until 1989, by which time the novel version of the story had already been out for five years. Although not particularly successful, the movie is an enjoyable adventure in which the main characters (played by Kris Kristofferson and Cheryl Ladd) experience events in a different order due to the effects of time travel.

Hollywood proved an enormous distraction to Varley’s literary pursuits. Not until 1992, eight years after completing the “Gaea” trilogy, did he release another novel. But “Steel Beach”—a kind of reboot of the “Eight Worlds” series—was to become his single best book, and his most sustained exploration of the meaning of authenticity and independence. Set once again on the moon, after humanity has been chased from Earth by alien invaders, this story revolves around a reporter named Hildy Johnson, who suffers from depression but somehow keeps surviving her suicide attempts. Meanwhile, the master computer that supplies virtually every human need begins experiencing a form of depression, too. The cause, it turns out, is a sort of cultural ennui. “The better able I became at taking care of you,” the computer explains to Hildy in a therapeutic moment, “the less able you were to take care of yourselves.”

Humanity, tossed like a fish upon the “steel beach” of life on the moon, must evolve or die. Yet with all its needs and most of its whims provided for by a nearly omnipotent machine, mankind’s capacities for self-reliance and self-determination risk extinction. Hildy’s redemption only comes when she teams up with a gang of brilliant oddballs known as the Heinleiners, who are building their own spaceship to take them to the stars.

“Steel Beach” was followed by a sequel of sorts, “Golden Globe” (1998)—a moving story of an actor/con-man who escapes an abusive father—and a four-part series of novels that are homages to Heinlein’s “juveniles,” all of them featuring Varley’s trademarks: independent, clever characters guided by common sense instead of conformity, and more likely to build rockets in their garages than to complain about others not doing so. Above all, his characters often see exploring the unknown not just as an adventure, but as a path to the authentic, individual life—one that won’t be clean or easy, but will be earned, and therefore genuine, in a way that can never be true of the unexamined life that computerized mass production makes so cheap. It’s a theme that would have been familiar to Emerson, who wrote: “The civilized man has built a coach, but has lost the use of his feet. He is supported on crutches, but lacks so much support of muscle.”

Dreamers from the First

Qualities like these often give Varley’s stories a libertarian flavor, and “Golden Globe” even received the Prometheus Award for Best Libertarian Science Fiction. But he shies away from explicit ideological loyalties: “I have no grand theories for politics or society in general, no axe to grind,” he told an interviewer in 2015. “As for Libertarianism, I go along with those folks up to a certain point, and then they propose something completely stupid.” Rather than using his stories as platforms for propaganda, Varley prefers to focus on the lives of his characters and the sense of the world they inhabit—for good or ill. Throughout it all, however, there remains the sense that self-determination—not just political liberty, but spiritual autonomy—is crucial to a life of meaning.

Varley’s avoidance of explicit ideology may be one reason why, despite the excellence of his work, he has never become the household name that a number of his contemporaries in the field, such as Ursula K. Le Guin and Philip K. Dick, have. Some aspects of his stories are so wildly imaginative that it was impossible until recently to imagine filming them. But in other ways, his fiction is too subtle for Hollywood producers. “Goodbye, Robinson Crusoe,” for example, which, despite its exotic locale (an artificial tropical paradise under the surface of Pluto), is ultimately about the experience of growing up—or “Blue Champagne,” which is about prioritizing love over material success—isn’t the material for summer blockbusters. Varley has consequently remained a figure of the bookshelf rather than the silver screen—once again following in the footsteps of the under-filmed Heinlein.

Varley retired in 2023 following the death of his wife, and he has almost never spoken publicly about the deeper themes of his work. Yet in a 1981 speech to a science fiction convention, Varley’s close friend, George R.R. Martin, managed to explain what motivated the science fiction authors who emerged from the hippie era, in words that precisely capture what makes Varley’s writing special:

[T]his generation … represents a fusion of the two warring camps of the ’60s. We were the first children of the Space Age, postwar babies still in school when Sputnik was launched…. Yet we were also the generation of Vietnam, the flower children and anarchists and peaceniks of the ’60s, disillusioned, questioning, idealistic. The New Wave was part of that, a sign of the ferment of the times…. [W]hat I think [Varley and his colleagues are] about, at heart, [is] combining the color and verve and unconscious power of the best of traditional SF with the literary concerns of the New Wave. Mating the poet with the rocketeer. Some of us fail, of course. We’re only human. But I do think we try. I told you we were an idealistic bunch, didn’t I? Dreamers from the first.

That distinctive blend of poetry and engineering—of idealism and realism—has animated the best of American literature since the days of Emerson. The hippie generation gave it a new boost: enough, in fact, to put it into orbit. For Varley, reaching out to the stars has also offered the chance to find more of what lies within the human soul. As a character remarks at the end of “Steel Beach,” “Your wildest dream and your worst nightmare all could be out there…. Think what a story it’ll be.”