John Lewis Learned Good Trouble from the Black Church

Long a force for change, the Black church still has important work to do

By Rachel S. Ferguson

In the midst of a pandemic, protests, and riots, we have buried civil rights icon John Lewis. But one thing has been missing from much of the coverage of Lewis’s death and funeral service. In a recent tweet, the theologian Fleming Rutledge recounted, “I spent the day in the car, so I was listening to hours of coverage about John Lewis. Not a single mention of his Christian faith or the Black church in hours of listening. It’s like a conspiracy of silence.”

This observation points to something deeper—really, it’s something different entirely—than complaints about checkout clerks who say “Happy Holidays” or religiously neutral Starbucks cups at Christmastime. As Eric Lincoln and Lawrence Mamiya put in in their landmark study of the Black church, The Black Church in the African American Experience, “The Black Church has no challenger as the cultural womb of the black community.” And yet, National Public Radio neglected to mention that Lewis was an ordained Baptist minister who preached his first sermon at 16.

Famously, Lewis had been beaten bloody a few years earlier during the Montgomery bus boycott. Even as a young teenager, he had a penchant for getting into “good trouble.” Much later in life, a member of the White mob who had attacked Lewis in the bus station, Elwin Wilson, approached Lewis, repentant for his racist assaults and involvement with the Ku Klux Klan. Lewis, who by that time was serving in Congress, forgave Wilson without hesitation, citing the philosophy of nonviolence and reconciliation that undergirded his whole life and work.

And where did he get this philosophy? Lewis said that “what Dr. King was saying in his speeches was in keeping with the teaching of Jesus. So I readily accepted . . . the philosophy and the discipline of nonviolence.” He added, “We were taught to respect the dignity and the worth of every human being and never give up on anyone, to try to reach them with kindness, with hope and faith and love.”

Photo of John Lewis by Michael Reynolds/Getty Images

Slavery and Christianity

In the early days of slavery, plantation owners didn’t tell slaves about Christianity and refused missionary efforts for fear that religion and faith might lead to unrest and revolt. Nevertheless, Christian worship spread through the slave community during the First Great Awakening of the 1730s and 1740s. Ultimately, missionaries were allowed to interact with slaves (a move that was also an attempt to appease abolitionists, who had begun to attack the practice of slavery) but were required to edit the Bible and preach only against stealing and in favor of obedience to masters.

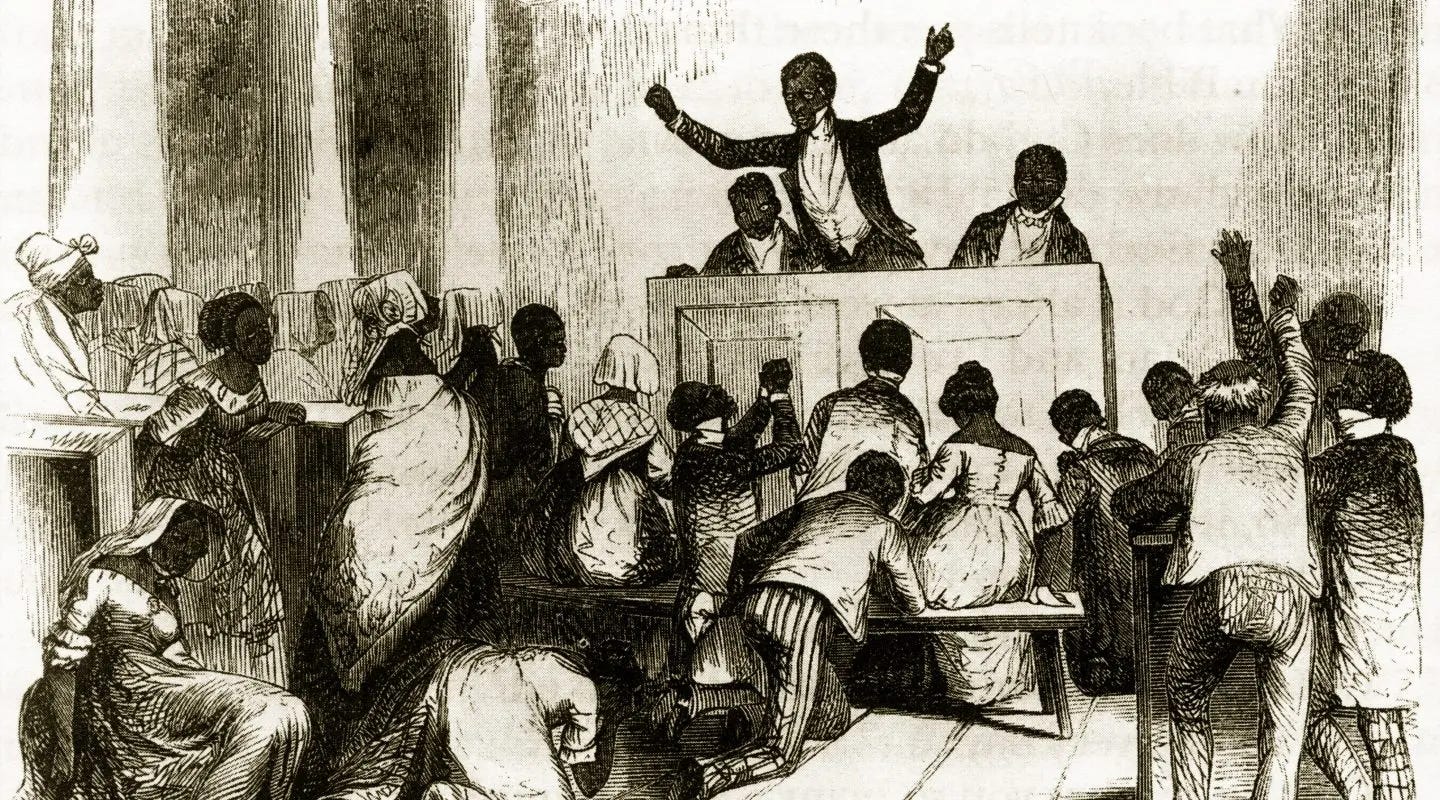

But the real worship wasn’t happening in the compliant services of the plantation missionaries. It had already taken root and spread like wildfire through the slave community, with secret night singing and prayer meetings held in defiance. The Black church was Israel, the White enslaver, Pharaoh. God would deliver.

As open Black congregations developed, White communities tried to maintain some form of control. But, as they were unwilling to worship with Black churchgoers, Whites inadvertently created an arena of independence, where Black congregants had real decision-making power and a strong sense of personhood.

The Importance of the Black Church

In the Black church, humanity’s story starts with the creation of humans in the image of God, not with sin. Israel’s story and the prophets are as important as Paul, and there is no contradiction between individual redemption and redemption of broken social structures. Not surprisingly, the church was—and is—a Black institution, one that gave birth to the great movements for economic uplift and civil rights and that continues to function as a center of Black life. Today, roughly 80 percent of Black Americans identify as Christian, and Black millennials are more likely to be certain about the existence of God, to pray, and to attend church services than their White peers.

A new generation is rediscovering the deep African roots of Christianity, too. It’s not just about early North African church fathers. Ethiopia and Nubia persisted in their commitment to Christianity throughout the medieval period, under incredible pressure from Islam. Today, more than half the population of sub-Saharan Africa is Christian. True Christianity was never the “White man’s religion” in the first place, and it certainly isn’t now, when less than a third of the world’s Christians are White. If we’re worried that upper-income White America has been defining our reality and the terms of our debates for too long, then let’s drop the parochialism and let Black America speak for itself.

The Black church as the foundation for the civil rights movement shows us what it means to have strong social institutions. The Black church is neither marketplace nor state, and it’s bigger than a lone family. It is a hub for cooperation and organization of the most sophisticated sort. To take just one example, there is no Montgomery bus boycott without the Black church because there would have been no Rev. James Lawson mentoring John Lewis and other students on the philosophy of nonviolence in the basement of Memorial United Methodist.

Likewise, there would have been no Martin Luther King Jr. to run the Montgomery Improvement Association. And there would have been no network of trusted friends to drive boycotters to work for 381 days! Powerful, well-organized, and effective movements for change spring from substantive ideas and established networks.

Given the challenges facing many African Americans, the Black church continues to be an important force for change. And there is no lack of opportunities. For instance, in light of the Supreme Court’s recent Espinoza v. Montana decision, the possibilities for supporting religiously based education in inner cities are opening up. The Black church is perfectly positioned to be the center of innovative, caring, meaningful education alternatives for struggling kids in tough circumstances.

Many elites want to talk about racial justice but can’t comprehend the centrality of the church to the Black American experience. To reclaim the church as a resource for today’s struggles and solutions, I think it might be time to get in some “good trouble,” don’t you?