‘Japan Inc.’ and Other Tales of Industrial Policy Apocalypse

As the U.S. deals with a rising China, it can learn from Japan’s history of industrial policymaking

America is in collapse. Industry is hollowing out. The country is falling behind in key technology sectors. And an Asian country is set to take over as the leading global power.

You might think this is another story about America’s current economic situation and the growing threat posed by China. Actually, I’m talking about Japan and the supposed threat it presented to the United States in the 1980s and early 1990s.

American pundits and policymakers are today raising a litany of complaints about Chinese industrial policies, trade practices, industrial espionage and military expansion. Some of these concerns have merit. In each case, however, it is easy to find identical fears that were raised about Japan a generation ago. To quote baseball legend Yogi Berra, it’s “déjà vu all over again.”

Revisiting the era of what critics called “Japan Inc.” or “the Japan Model” provides some important lessons regarding how debates over China might unfold in coming years. China’s human rights abuses, anti-democratic tendencies and growing military aspirations make it a far more serious threat to U.S. interests than Japan ever was. Nonetheless, the panic about Japan and its economic planning efforts remains instructive, especially with a massive 1,500-page, $250 billion industrial policy bill recently passing in the Senate and political interest in countering China at an all-time high.

Japan’s Rebound

The 1970s were a challenging economic decade for the U.S., with rising inflation, declining productivity and a deteriorating market outlook for once-mighty sectors such as steel, automobiles and consumer electronics. Many Americans started looking for culprits to blame for these woes. Attention turned quickly toward Japan, which was enjoying a postwar boom in many of those same areas.

In 1949, the Japanese government created the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) to work with other government bodies (especially the Bank of Japan) to devise plans for industrial sectors in which they hoped to make advances. Although not as heavy-handed as Chinese planning authorities are today, MITI came to have enormous influence over private-sector research and investment decisions during the next five decades. The organization used a variety of the same policy levers that Chinese officials do today, with a particular focus on trade management and industrial policy investments in sectors perceived to be “strategic” for future economic advance.

It is often difficult to untangle the many variables that influence innovation and economic growth, and that is particularly true for industrial policy initiatives. By the late 1970s, however, U.S. officials and market analysts came to view MITI with a combination of reverence and revulsion, believing that it had concocted an industrial policy cocktail that was fueling Japan’s success at the expense of American companies and interests.

Rising Interest in the Rising Sun

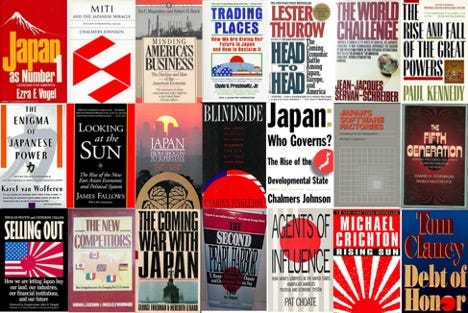

Japan’s success resulted in an explosion of American interest in Japanese economic planning and MITI in particular. In 1979, Ezra F. Vogel’s “Japan as Number One: Lessons for America” became a surprise bestseller and jump-started interest in Japanese culture and industrial planning efforts. Vogel looked at Japanese efforts with fawning admiration and expressed exasperation with Americans who avoided “acknowledging Japan’s superior competitiveness.” He claimed that “America’s institutions are not strong enough to guide these developments or to respond effectively to the problems of its declining economic competitiveness.” While decrying the failures of the American administrative state, he called for the U.S. to create a new breed of bureaucrat: an elite corps of long-term industrial planners who would mimic MITI’s approach to industrial oversight.

A few years later, Chalmers Johnson made a similar case in his 1982 book, “MITI and the Japanese Miracle: The Growth of Industrial Policy, 1925-1975.” Johnson credited MITI and other Japanese institutions with creating an effective “developmental state” that combined protectionism, industrial planning and other adjustments to economic systems “in the cause of national interest as the term national interest is understood by MITI officials.” That same year, Ira Magaziner and Robert Reich released a comprehensive MITI-esque industrial policy blueprint for America in their book, “Minding America's Business: The Decline and Rise of the American Economy.” They claimed that “without government support, American business will find it increasingly difficult to achieve competitive leadership in today’s international environment.”

These authors and other American intellectuals of this period tended to admire Japanese culture and stressed Japan’s supposedly superior commitment to working in a communitarian fashion. For example, Vogel argued that the Japanese better appreciated “the values of group life” and that they were “on the forefront of making large organizations something people enjoy.” Vogel and these other scholars simultaneously denounced America’s individualism and culture of independence that shunned top-down authority and obedience to the plans trusted elites established for society.

A 1981 New York Times op-ed by John Curtis Perry even called on Japan “to come here, occupy us, and do exactly those things we did for them from 1945 to 1952.” Just as U.S. forces oversaw the Japanese recovery following the war, “the Japanese would rule America indirectly” and completely remake American society. As outlandish as it was, Perry’s essay reflected the warm embrace of Japanese culture and top-down planning by many academics during this period.

MITI Mania

While some scholars did, in fact, extol Japanese culture and top-down planning, others viewed Japanese success with greater suspicion and saw the country more as an adversary that needed to be challenged. Just as the Cold War with the Soviet Union was winding down, a new type of geopolitical conflict with Japan was being forecast or fueled by more hawkish analysts, many of whom used militaristic metaphors when discussing industrial policy.

For example, in 1985 the New York Times Magazine published a long feature on “The Danger from Japan” by Theodore H. White. White, a long-standing Asia reporter, recast Japan’s recent economic success as a continuation of the Second World War and suggested that “40 years after the end of World War II, the Japanese are on the move again in one of history’s most brilliant commercial offensives, as they go about dismantling American industry.” Once again, MITI was the mastermind. “MITI defines strategies; Japanese private enterprise follows through with zest. No better marriage of government planning and private enterprise has ever been seen,” White proclaimed.

White’s essay played into the growing fears that America had been duped by Japan and that the two countries were “Trading Places,” as a 1988 book by Clyde V. Prestowitz suggested. Prestowitz, a former Reagan administration trade official, argued that if America did not jump on the industrial policy bandwagon, it risked becoming an economic “colony‐in‐the‐making.” He was so enamored with the MITI planning model that he proclaimed audaciously, “The power behind the Japanese juggernaut cannot stop of its own volition, for Japan has created a kind of automatic wealth machine, perhaps the first since King Midas.” He wanted the U.S. to match and surpass Japanese planning efforts and suggested that an unwillingness to do so was essentially a national security failure.

Other books made the case for growing Japanese superiority in “strategic” emerging technology sectors such as computing, software and even early artificial intelligence efforts. Edward A. Feigenbaum and Pamela McCorduck’s “The Fifth Generation: Artificial Intelligence and Japan’s Computer Challenge to the World” (1983) and Michael A. Cusumano’s “Japan’s Software Factories: A Challenge to U.S. Management” (1991) exemplified this thinking. MITI and other Japanese bureaucracies were outthinking their U.S. counterparts, and it was only a matter of time till the U.S. lost competitive advantage in other sectors, which could also have security implications.

All this hyperventilating about Japan was also happening while books such as Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber’s “The World Challenge” (1981) and Paul Kennedy’s “The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers” (1989) predicted the impending close of the “American Century.” America was facing what many considered an existential threat, and its old ways of thinking about markets and planning had to be discarded.

Japan-Bashing Reaches Its Peak

By the end of the 1980s, fears about “Japan Inc.” had reached a fever pitch. On top of all the hand-wringing about MITI’s planning efforts and growing trade imbalances, Japanese investments in America became a major concern. Japanese real estate investments in iconic American properties such as Rockefeller Center and the Pebble Beach Golf Resort made the nightly news. The title of a 1990 book by business journalists Douglas Frantz and Catherine Collins reflected the tone of public debates: “Selling Out: How We Are Letting Japan Buy Our Land, Our Industries, Our Financial Institutions, and Our Future.” While interest in U.S. properties was not unique to Japan—American properties were highly valued assets across the globe—the broader Japan panic infecting America during this period made their direct investments feel like a concerted “invasion” of sorts, even as those investments began plummeting after 1990.

Book publishers seized upon the prevailing zeitgeist and capitalized on growing Japan phobias with even more extreme titles. The most nefarious-sounding scenarios could be found in Pat Choate’s “Agents of Influence: How Japan’s Lobbyists in the United States Manipulate America’s Political and Economic System” (1990) and another book he co-edited with T. Boone Pickens and Christopher Burke, “The Second Pearl Harbor: Say No to Japan” (1992). These books suggested savvy Japanese operatives were lurking in the shadows, actively undermining American interests.

The danger of rising Japanese power seemed so palpable that George Friedman and Meredith Lebard’s 1991 book “The Coming War with Japan” received serious attention as a potential script for what seemed like the real possibility that economic squabbles between countries would boil over into another conflict in the Pacific. Meanwhile, Donald Trump was running full-page ads in The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Boston Globe in 1987 decrying how “for decades, Japan and other nations have been taking advantage of the United States.”

Popular fiction was simultaneously fanning the flames of anti-Japanese sentiment. Michael Crichton’s “Rising Sun” (1992) and Tom Clancy’s “Debt of Honor” (1994) offered up plots that made Japanese businessmen and politicians the bad guys—including characters covering up a murder and flying planes into the U.S. Capitol. Commenting on Crichton’s novel in 1992, Washington Post columnist Robert J. Samuelson observed that the book reflected a swelling “loathing of Japan” and that its “Japanese characters are such vile people that it’s hard to imagine any self-respecting Japanese actor taking a role.”

And yet the movie adaptation arrived a year later with many Japanese American actors starring alongside Sean Connery and Wesley Snipes. It became a box-office smash. Less flamboyantly, a Michael Keaton-led movie called “Gung Ho” featured Japanese executives taking over an American auto plant to whip the lazy workers into shape.

Up on Capitol Hill, things got uglier and took on a racial tinge. Democratic Texas Rep. Jack Brooks expressed regret that Harry Truman had dropped only two nuclear bombs on Japan when “he should have dropped four.” Similarly, Sen. Ernest F. Hollings (D-S.C.) openly joked that the American atomic bomb was “tested in Japan.” Meanwhile, Republican Sen. John Danforth of Missouri called the Japanese “leeches.” No wonder, then, that in a 1989 Wall Street Journal op-ed, David Boaz of the Cato Institute concluded that “Yellow Peril Reinfects America,” with a resurgence of anti-Asian sentiment not seen since World War II. Congressional lawmakers even made Japan-bashing a literal affair: Several members of Congress gathered on the lawn of the U.S. Capitol in 1987 to smash Japanese electronics with sledgehammers.

While things calmed down a bit by the mid-1990s, books and columns were still predicting that Japan would eventually eat America’s lunch. “Looking at the Sun: The Rise of the New East Asian Economic and Political System” by James Fallows and Eamonn Fingleton’s “Blindside: Why Japan Is Still on Track To Overtake the U.S. by the Year 2000” were both published in 1995. Chalmers Johnson reappeared on the scene to double down on his earlier predictions, insisting in his 1996 book, “Japan: Who Governs? The Rise of the Developmental State,” that “Japan’s combination of a strong state, industrial policy, producer economics and managerial autonomy seems destined to lie at the center, rather than the periphery, of what economists will teach their students in the next century.” Unfortunately for Johnson, reality intervened and economists began teaching their students some very different lessons about Japan Inc.

From Fears to Farce

Just as Japan phobia was reaching its zenith in the early 1990s, Japan’s fortunes began taking a turn for the worse. The Japanese stock market crashed in 1990 due to real estate overvaluations, monetary policy miscalculations, a variety of other macroeconomic factors and a lot of garden-variety corruption, from government officials on down to average citizens. The Nikkei Index peaked at 38,915.87 on Dec. 29, 1989, then began a dramatic fall. It has never reached that level since.

Ironically, while Vogel’s “Japan as Number One” had helped kick off the earlier Japan adoration era, he concluded his book with some warning signs for Japan that proved quite prescient. Those factors included the end of the low-hanging-fruit period of “catch-up” modernization, increasing competition from other Asian nations such as Korea and Taiwan, natural resource limitations, declining population growth and the end of easy overseas trade expansion. Many of these realities started catching up with Japan in the 1990s, and in combination with the market crash, Japan suffered a brutal economic downturn that became known as the Lost Decade, which really lasted almost two decades.

Microeconomic planning failures—including many missteps by MITI—were also becoming evident during this time. MITI had made a variety of industrial policy bets that were originally feared by U.S. pundits, only to become embarrassing failures a few years after inception. Most notable in this regard were Japanese efforts to plan for future high-tech sectors, such as high-definition television (HDTV) and advanced computing.

Japan had developed working HDTV prototypes by 1979, leading some U.S. industrial policy hawks like Prestowitz to claim that this was an “example of the widening U.S. lag” in high technology. But Japan’s industrial policy bet was on an analog high-definition standard that they would have to abandon by 1994 after acknowledging that the digital format favored by U.S. developers would prevail. This was just six years after Prestowitz had mistakenly proclaimed that “there are not even any Americans involved in this struggle.”

Another MITI bad bet was its Fifth Generation Computer Systems initiative. Launched in 1982 to promote advances in supercomputing and artificial intelligence, MITI shut down the program just 10 years later after burning $400 million on software that it would end up giving away freely because no one wanted it. Even in areas where Japanese industrial policy may have helped a bit early on—such as flat-screen computer display technology—Japan lost many of those gains as lower-cost competitors in Korea and China grabbed market share.

Other industrial planning failures by MITI became obvious over time, and by the late 1990s many scholars came to view most Japanese industrial policy initiatives as a costly bust. Marcus Noland of the Peterson Institute for International Economics noted in a 2007 study of Japanese industrial policy efforts, “Attempts to formally model past industrial policy interventions uniformly uncover little, if any, positive impact on productivity, growth, or welfare. The evidence indicates that most resource flows went to large, politically influential ‘backward’ sectors, suggesting that political economy considerations may be central to the apparent ineffectiveness of Japanese industrial policy.”

Noland found that “corruption was encouraged by the policy-instigated creation and distribution of rents” and that public intervention and financing had crowded out not just private financing, but also the development of private-financing knowledge and capabilities for many important emerging sectors. It was one of the many reasons American venture capitalists were able to take such a commanding lead in funneling massive investment into digital-era computing and internet companies.

Combined with Japan’s stumble and America’s ascendancy in many high-tech sectors, the infatuation with MITI faded rapidly by the end of the century, and the intellectual tide turned hard against the wisdom of industrial policy more generally. The romantic view of state planning found in the earlier Japan Inc. books and essays gave way to more sober assessments of its limits.

Perhaps most notable in this regard was the Japanese government’s own admission that the MITI model had not worked as well as planned. A 2000 report by the Policy Research Institute within Japan’s Ministry of Finance concluded that “the Japanese model was not the source of Japanese competitiveness but the cause of our failure.” MITI was renamed the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry at about the same time, and its mission shifted more toward market-oriented reforms.

Lessons for Today

Despite this, we hear echoes from the Japan Inc. era debates in today’s policy discussions about China and industrial policy planning. Newer books sport titles that seemingly just erased “Japan” and substituted “China” in its place: “China Inc.,” “The Coming China Wars,” “Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap?” Even Prestowitz is back with a new book that simply shifts attention from Japan to China (“The World Turned Upside Down: America, China, and the Struggle for Global Leadership”). These rhetorical tactics sold books and grabbed headlines in the past, and they continue to do so today as anti-Chinese sentiment replaces the anti-Japanese resentment of a generation ago.

This similarity demonstrates the first lesson we can learn from the previous era: It is important to separate serious geopolitical and economic analysis from breathless fear-mongering and borderline xenophobia. The former has a serious place in policy discussions; the latter needs to be called out and shunned. After all, there are many legitimate worries about rising Chinese power, particularly when it involves Chinese Communist Party efforts to squash human rights domestically or to engage in industrial espionage, trade mercantilism and military adventurism abroad. Separating serious matters from trivial or imaginary ones is crucial, especially to help keep peace between nations. Avoiding hysteria is especially pertinent today with a wave of anti-Asian sentiment and attacks on the rise in the U.S.

A second lesson from the Japan Inc. experience relates to today’s renewed interest in industrial policy: Forecasting the future of nations and economies—and trying to plan for it—is a tricky business. A huge range of variables affects global competitiveness and technological advancement. A nonexhaustive list of some of the most important factors would include legal and political stability, physical and intellectual property rights, tax burdens, competition policy, trade and investment laws, monetary policy, research and development efforts, and even demographic factors and access to certain natural resources. Understanding how these and other factors all work together is an inexact science. When targeted industrial policy mechanisms are added to the mix, it becomes even harder to untangle which variables are making the most difference.

Both in the past and today, a less visible group of scholars has suggested that an embrace of entrepreneurialism and free trade was the fundamental factor driving Japanese economic expansion in the past and China’s amazing growth today. Openness to markets, they say, drove the enormous economic expansions—which also happened during times of much-needed catch-up modernization in both countries. But these perspectives have usually been shouted out of the room by louder voices, who either bombastically blast or praise industrial policy mechanisms as the prime mover in the economic rejuvenation of both nations.

We need to tamp down on the magical thinking that governments can easily achieve technological innovation and economic growth by simply spinning a few industrial policy gauges. A few big bets may pay off, but that doesn’t justify governments engaging in casino economics regularly. History more often shows that grandiose industrial policy schemes simply result in cost overruns, cronyism and even corruption.

Perhaps the most ironic indictment of industrial policy punditry lies in the way all the earlier books and essays about Japanese planning not only failed to forecast the many flops associated with it, but also did not foresee China as a potential future economic juggernaut. Korea, Singapore and Taiwan were mentioned as potential Asian challengers, but no one gave China much consideration. What might that tell us about the ability of experts to predict the future course of countries and economies? It is a reminder of the wisdom of another great Yogi Berra quote: “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.”

The author wishes to thank Scott Lincicome, Dan Griswold, Christine McDaniel, Pat DiFrancesco and Krista Mitchell for reviewing this essay and offering helpful suggestions.