It’s Time To Take “Yes” for an Answer

By Kevin Pham

COVID-19 metrics, including new cases, hospitalizations and deaths, have been declining rapidly for several consecutive weeks since Jan. 12. There are likely several reasons contributing to this welcome phenomenon, including the end of the holiday travel season, the deployment of tens of millions of vaccine doses, and the natural end of a very large spike in cases that lasted from September to January.

One thing different about this spike, compared to the previous two spikes in the spring and then early summer, is the rate of decline. For instance, as of this writing, hospitalizations have dropped by 60% in under six weeks. By contrast, the summer spike took approximately 10 weeks to reach a nadir in September that was 50% of its peak.

This may be a hint that we are approaching herd immunity. According to at least one prominent medical professional, Dr. Marty Makary, we will have achieved herd immunity by April. By Makary’s calculation and estimation, approximately 55% of Americans have been infected with COVID-19. Combine that figure with the 19.9% of American adults who, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, have received at least one dose of the vaccine, and that adds up to roughly 7 in 10 American adults having at least some level of immunity to the virus.

The immunity rate required for herd immunity depends on the viral reproduction rate; the more infectious the virus is, the higher the necessary percentage of people with immunity. The most pessimistic estimates of SARS-CoV-2’s infectiousness would require a herd immunity rate of 80%, which, based on Makary’s estimates, should be achievable soon.

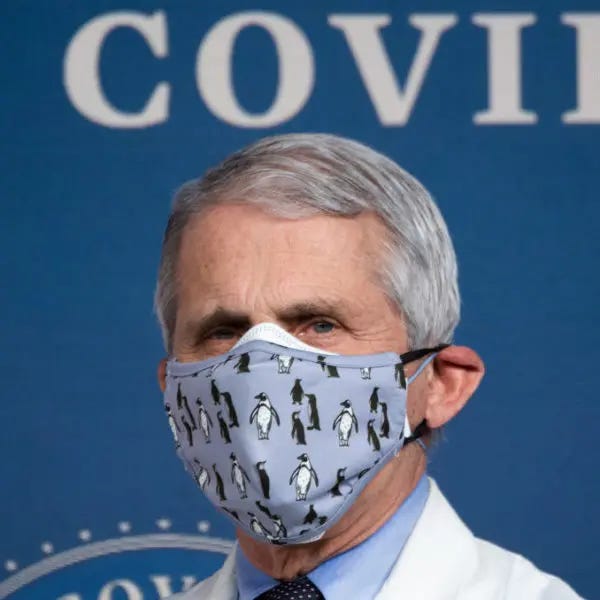

But not everyone is so bullish about reopening. In a recent interview with Fox News’ Bret Baier, Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and President Biden’s chief medical adviser on COVID-19, said it was conceivable that virus mitigation measures could be pulled back by late fall of this year.

That’s a lot of hedging for a fairly conservative prediction. Much of it boils down to uncertainty. Understandably, the culture in public health tends to err on the side of caution. When it comes to the public’s welfare, it takes some white-knuckle policymaking to trust ordinary people with their own health. Nobody wants to be the one responsible for relaxing a measure that, if followed, would have prevented the next death.

So, while Makary’s estimates are extrapolations that reasonably assume a large number of infections go unreported, it is not surprising that many public health officials see things differently. And, indeed, based on laboratory-confirmed cases, only 8.7% of the American population has tested positive for COVID. Even combining this percentage of confirmed cases with the share of Americans vaccinated means that fewer than 1 in 5 Americans has any kind of immunity. The waters are further muddied by the fact that we still don’t fully understand how much immunity those who have recovered from COVID-19 actually have.

For the public health officer having to make a decision, it is easier to rest on these numbers and facts and overly cautious safety measures than to rely on extrapolated optimism and the public’s good sense and wisdom. But this is not how good governance works. We know that infections have spread much further than what is suggested by laboratory confirmations, and we have clinical trials and national experiences that the vaccines are working. Furthermore, the precipitous drop in COVID-19 numbers aligns perfectly with what we know about the virus.

A scientist working on the basic virology of SARS-CoV-2, or an epidemiologist cataloguing the spread of the pandemic, may focus only on the virus and its impact, to the exclusion of all else. We may even compliment these researchers for their diligence. But when policymakers who enact laws and rules have this level of focus, it is called tunnel vision.

The reticence to relinquish pandemic precautions may come from a place of true concern for health, but the measures we have taken affect a much greater part of our lives than that which interacts with respiratory viruses, from the loss of so many livelihoods to the deterioration of our children’s mental health.

The virus is losing its grip on us. It is not gone yet, but the end of the pandemic may be near and it is time we take “yes” for an answer. To do otherwise is willful disregard of legitimate clinical knowledge won at a very dear price.