It’s Not Reagan’s Party Anymore

The Republican Party has abandoned the ideas that made America great again

Is the GOP still Ronald Reagan’s party? There are some people trying to convince us that it is, including Henry Olsen here at Discourse.

I can think of a lot of reasons why people would want to believe this, but it is mostly for a reason that undermines this very claim. After initially rejecting Donald Trump en masse, conservative intellectuals have been dragged by professional pressure and reflexive partisanship—and, to be sure, by the often unappealing alternatives—to come around to supporting him. The more they get pulled from Reaganism to what National Review once accurately called “free-floating populism with strong-man overtones,” the more they have to insist that nothing has really changed.

The Happy Warrior

The first reason this claim doesn’t pass the snort test—you cannot hear it without involuntarily snorting in derision—is because Donald Trump is so completely different from Reagan in his style. Reagan was as optimistic as Trump is apocalyptic, as humble as Trump is vain, as charismatically likeable as Trump is combative and off-putting and as personally wholesome as Trump is seedy. Let’s just say that one could not conceive of a Reagan scandal involving paying hush money to a porn star.

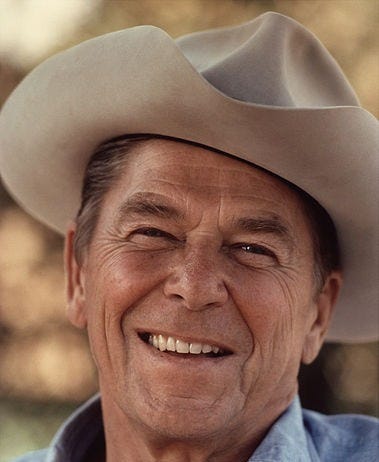

The emblematic image of Reagan is probably something like this:

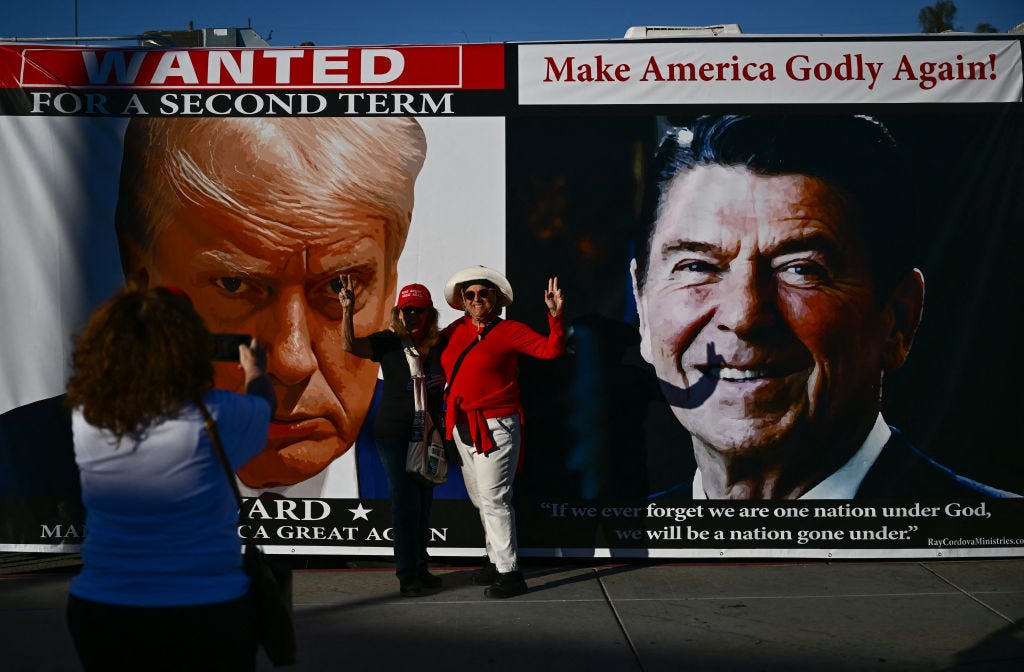

While the emblematic image of Trump is likely something like this:

One of these things is not like the other.

This has given rise to the claim that some of us don’t like Trump just because of his style. But Trump has also precipitated an important change in ideological substance.

Tariff Man vs. the Great Communicator

Henry Olsen’s main argument is that, while Reagan is associated with pro-free-market, small-government policies, he was not consistent about them and was willing to make pragmatic departures. Don’t I know it. This is one of the reasons I’ve always been more reserved in my admiration for Reagan. Republicans used to venerate Reagan while railing against the compromises of the weak-kneed Republican “establishment”—even though both made many of the same compromises.

But if Reagan wasn’t consistent, he still set a clear overall direction and ideal for U.S. policy: unleashing private enterprise and free markets as the alternative to failed Big Government interventions. Olsen talks about Reagan standing for “faith, family and community.” But he conspicuously doesn’t mention “freedom,” and especially economic freedom. But Reagan couldn’t stop talking about it.

The area where we see this most sharply is on trade. Reagan imposed a few tariffs in response to political pressure. But he famously declared, “There are no winners in a trade war,” and denounced protectionism as a “no-growth policy” that “costs consumers billions of dollars, damages the overall economy, and destroys jobs.” This is a case he made again and again, giving speeches on “the folly of protectionism.” When he did impose tariffs, he defended them only as an unfortunate retaliatory measure intended to lead to negotiations for greater trade freedom by convincing our partners to lower their barriers, too.

By contrast, Donald Trump confidently declared that “trade wars are good, and easy to win,” an assertion he ultimately disproved by losing a number of these so-called wars, most famously with China. Meanwhile, Trump is promising a much bigger trade war in his second term, with massively expanded tariffs. According to the New York Times,

He has proposed “universal baseline tariffs on most foreign products,” including higher levies on certain countries that devalue their currency. In interviews, he has floated plans for a 10 percent tariff on most imports and a tariff of 60 percent or more on Chinese goods.

Trump has even adopted the moniker “Tariff Man” for himself.

Where Reagan expressed a distrust of bureaucrats picking winners and losers, Missouri Senator Josh Hawley—one of the Republican Party’s rising stars in the Trump era—has proposed to give vast powers to the Commerce Department that would have the effect of subjecting every decision about the global supply chain to the approval of a bureaucrat.

Trump and his followers in the party have adopted the same approach to other issues, such as antitrust, which they want to use as a bludgeon against political enemies, particularly big tech companies. Trump’s running mate J.D. Vance said earlier this year that the Justice Department should target Google in part because the company is “explicitly progressive” in its political and cultural views.

No, Reagan’s party was never fully consistent about the free market. But it did have a strong preference for the free market, and it gave significant voice to pro-free-marketers. Olsen claims that Reagan was not a “free market fundamentalist”—yet this is a phrase recently borrowed from the left by conservative advocates of “industrial policy,” which is just central economic planning by another new name. The use of the term “free market fundamentalism” as a pejorative is a symbol of the very change Olsen denies.

The Leader of the Free World

If there is one thing Reagan stood for above all, it is the strength and vigor of America’s leadership in the world.

He pursued this policy not just through a military buildup that outcompeted the Soviet Union, but through diplomatic leadership and a willingness to use America’s strength. The center of his policy was the deployment of intermediate-range nuclear missiles to Europe, in response to a previous Soviet deployment that held every city in Western Europe under direct nuclear blackmail. Critics denounced this as a wildly provocative act, but Reagan rallied NATO support for it, and it worked. The Soviets began to withdraw their missiles and eventually signed a treaty to remove them. Then their inability to respond to the Reagan military buildup contributed to the collapse of their Eastern European empire.

The center of Donald Trump’s foreign policy is retreat from American leadership. Trump has a mercantilist, zero-sum view of the world in which any help offered by America to its allies is a loss for us. He has questioned whether we should support Taiwan because “Taiwan took our chip business from us.” He has repeatedly flirted with a U.S. withdrawal from NATO.

Early this year, the Chicago Council on Global Affairs released a striking survey result:

For the first time in the nearly 50-year history of the Chicago Council Survey, a majority of Republicans in 2023 said it would be best for the future of the United States to stay out of—rather than take an active part in—world affairs. This reflects a major shift in public opinion since 2015, when GOP supporters were more likely than Democrats to favor an active role abroad. What’s driving the drop in support? A closer look at the data reveals “Trump Republicans,” which make up 47 percent of Republican Party supporters, are much more negative than other “non-Trump Republicans” about the US global role in general, US alliances with Europe, and defending allies.

Nowhere can this be seen more clearly than in U.S. policy toward Ukraine. It has become the party line among Trump’s followers that it was American provocation—the expansion of NATO—that in Trump’s words “almost forced” Russia to invade Ukraine. J.D. Vance has boasted, “I won’t even take calls from Ukraine.” Earlier, he said, “I gotta be honest with you, I don’t really care what happens to Ukraine one way or another.” This led at least one old Reaganite, National Review’s Jay Nordlinger, to conclude:

This blame-America stuff used to gall Republicans. We used to excoriate the left for it. Now it is trumpeted from the GOP convention platform. Reagan had a line: “I didn’t leave my party; my party left me.”

This isn’t just talk or speculation about what Trump might do in another term in office. It’s what he and his supporters are already doing. After Trump expressed disapproval of U.S. aid to Ukraine, a Republican faction in Congress held up the aid for months, which was a significant cause of Ukrainian losses on the battlefield earlier this year.

Trump and his supporters call their policy “America First,” but it is actually America Last: Trump’s America would be last to take the initiative to promote our interests, support our allies or promote our ideals.

The Great Transmogrification

If all of this were not enough, there is one issue on which Trump’s style acquires a substance all its own: immigration.

Trump launched his first presidential bid by accusing Mexican immigrants of being rapists, and in this campaign, he has accused immigrants of “poisoning the blood of our country” and coming from “mental institutions and prisons all over the world.” This is a lie he has repeatedly told, for which there is no basis—other than his own prejudice.

He has been giving these claims an increasingly racist angle, spreading memes that warn of “Third World” immigration by raising the prospect of Black people overwhelming our pristine suburbs. I might have given Trump the benefit of the doubt on this, but it’s part of a long-standing pattern. From the beginning, Trump has been posting memes from white nationalists, calling neo-Nazis “very fine people” and having rabid antisemites over for dinner.

By contrast, Ronald Reagan knew how to forthrightly denounce racism, and his final speech as president has been described as a love letter to immigrants.

This, I believe, is one of the most important sources of America’s greatness. We lead the world because, unique among nations, we draw our people—our strength—from every country and every corner of the world. And by doing so we continuously renew and enrich our nation. While other countries cling to the stale past, here in America we breathe life into dreams. We create the future, and the world follows us into tomorrow. Thanks to each wave of new arrivals to this land of opportunity, we’re a nation forever young, forever bursting with energy and new ideas, and always on the cutting edge, always leading the world to the next frontier. This quality is vital to our future as a nation. If we ever closed the door to new Americans, our leadership in the world would soon be lost.

Olsen describes Reagan as a practitioner of a kind of blue-collar populism, appealing to “the wisdom and dignity of the average American.” But this is precisely how Reagan differed from Trump. Reagan appealed to the American common man by invoking his country’s highest ideals. Trump tries to appeal to the common man by stoking fear and hatred.

Many readers will remember the Calvin and Hobbes comic strip, in which Calvin had a cardboard box labeled “transmogrifier,” which would transform him (in his imagination) into various kinds of animals. “Transmogrify” was not created for the comic but is in fact a real word, and it has long been one of my favorites. It means “to transform in a grotesque manner.” That is the best word to describe what has happened to the Republican Party under Trump’s influence.

America no longer has a pro-free-market, pro-liberty political party. Its semi-pro-market party has turned populist, xenophobic and authoritarian.

It is a tragic change, because if there was a politician who actually did “make America great again,” it was Ronald Reagan. His policies and his leadership helped revive the American economy, unleashed a torrent of growth and innovation, fueled a new burst of American optimism and turned the tide of America’s fortunes in the Cold War.

We can’t keep America great by rejecting Reagan’s example—or by retroactively rewriting it.