It Takes More Than Words To Show How You Feel

Tales of repentance and atonement illustrate the importance of backing up apologies with actions

By James Broughel

In economics there is a concept called revealed preference, which can be summed up neatly with the popular expression “actions speak louder than words.” People say all manner of things, but if you want to know who they truly are and what they care about, look at what they do and not what they say.

The counterpart to revealed preference in religion is the idea of repentance. The New Testament, in particular the Gospels, devotes significant attention to how it is not enough simply to say, “I’m a sinner; I’m sorry.” People can easily say they’re sorry, but the real question is whether there is a corresponding behavior change to go along with the statement. For example, Jesus forgives a woman caught in adultery, but he also tells her to go and sin no more. When repenting, as with revealed preference, actions speak louder than words.

When the focus is on behavior, internal motivations seem to matter very little. Those who say they are going to quit drinking seem not to have meant it when they fall off the wagon a week later. A stronger version of this view is that certain actions are right or wrong, regardless of motivation. When I give money to a charity every month, maybe I genuinely care about the cause I’m giving to, or maybe I just do it for a tax write-off or to appear generous to impress my friends. Irrespective of the reason, I do what’s right; that’s the important thing.

One reason underlying motivations may not be that important is that doing the right thing is extremely difficult. There are so many social pressures encouraging us to seek status, wealth and power rather than help others. If we’re able to resist these temptations, perhaps the important thing is that we crossed the finish line, not how we got there. Mother Teresa spent her life giving to others at significant personal expense—does it really matter whether she did it out of altruism or because she selfishly sought sainthood for herself?

Taking the Long View of the Good Life

A lot of ink has been spilled among philosophers as to what the “good life” entails. Some philosophers focus on maximizing pleasure or utility, such as Epicurus, with his philosophy of hedonism, or Jeremy Bentham, the father of utilitarianism. These philosophies, with their traditional emphasis on feeling good in the present moment, differ significantly from the repentance view, whereby the good life involves a fair amount of suffering, at least in the short run.

Utilitarian: Jeremy Bentham. Image Credit: Henry William Pickersgill/Wikimedia Commons

There is a parallel concept in economics called time inconsistency. The Federal Reserve is struggling with a version of this problem right now. Inflation is higher than the Fed would like. To bring it down would involve rapidly raising interest rates in a manner that would likely cause a recession. In the long run, going through a recession might be a good thing because inflation rates would fall. But the short-run pressure on the Fed is to keep interest rates low to avoid the recession.

One can easily see the conflict here between short- and long-run interests. As Odysseus knew when he tied himself to the mast of his ship as he sailed past the Sirens, what brings short-term pleasure is often not in our long-term interests. And vice versa, a process of continual short-run pain and challenge often builds character and resilience over the long haul.

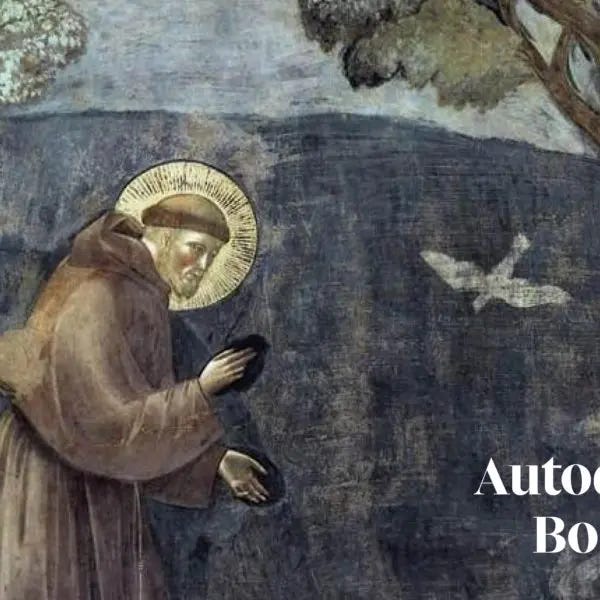

Consider the life of Saint Francis of Assisi. Francis was the son of a successful Italian merchant. Privileged for his time, he could easily have led a cozy life by following in his father’s footsteps. But instead, he gave up everything—his wealth, comfort, even opportunities for love—all to create a new congregation and to rebuild what at that time was a Catholic Church in disarray.

His story is captured elegantly in the 1961 film “Francis of Assisi,” written by the German author Louis de Wohl and starring Bradford Dillman as Francis. With the benefit of Hollywood hindsight, Francis seems, well, saintly. But his actions must have seemed crazy to those who knew him. One could imagine his friends and family asking Francis, “What is there to atone for? You have done nothing wrong. You are a good person. Maybe you are not perfect, but who is?” Yet Francis believed that renouncing his worldly possessions, though painful in the moment, would benefit both the world and his own soul in the long run.

Confronting mortality: Leo Tolstoy. Image Credit: Ilya Repin/Wikimedia Commons

In the short novel “The Death of Ivan Ilyich” by Leo Tolstoy, the protagonist confronts his own mortality upon learning he suffers a terminal condition. He wonders why he, a person who also seemingly did nothing wrong in life, must suffer such an unfortunate fate. One point of the novel is that going through the motions in a world full of evil is not enough. The evil must be confronted head on.

In the 1952 film “Ikiru”—which means “to live” in Japanese—a lifelong bureaucrat named Watanabe is diagnosed with stomach cancer. After having spent decades working in the Tokyo public affairs office, shuffling papers around but having little real-world impact, he undergoes a transformation. He dedicates his few remaining months to a single purpose: building a playground for neighborhood children. In rapid-fire succession, Watanabe packs more life into his final months than he had in the previous 30 years combined. He falls in love with a much younger woman, Toyo, and although the movie is vague about the extent of their physical intimacy, she brings vitality and youth to the dying man.

The Limits of Atonement

A less uplifting story about making amends for the past is the novel “Atonement,” by the English author Ian McEwan. The story begins shortly before the outbreak of World War II. When her cousin Lola is raped, a privileged and somewhat spoiled young girl named Briony bears false witness against Robbie, the housekeeper’s son. Robbie is in love with Briony’s sister, Cecilia. Thus, the novel is ultimately about Briony’s lifelong journey to come to terms with how she lied and stood in the way of true love. It also acknowledges the limitations of our efforts to make amends: Sometimes, no matter what we do, we can never truly atone for the harm we’ve caused.

McEwan’s meandering and, to be honest, somewhat long-winded style can leave the reader bored at times. One could also criticize the author for leaving his audience feeling tricked: The book has a surprise ending, which will disappoint those looking for a Hollywood finale. In that sense, watching the movie version of “Atonement,” starring Keira Knightley, is a smaller investment that may yield a similar reward.

The revealed-preference worldview tells us our actions and the impact we have on others are what count, not just following a correct script, so atonement requires reorienting our lives around an improved set of concrete actions. There is nothing wrong with saying the right thing; it just isn’t enough. When we make mistakes, we have to pay, because if we don’t, one way or another we’ll end up paying anyway.