In the U.S.’s Fight Against China, We’re at a Distinct Disadvantage

With corporate America in its corner, China is heavily favored in the battle between Washington and Beijing

We’re now officially in a presidential election year, and as the campaign trail heats up, China is sure to be a major conversation topic. Who will be tougher against China? Who is best prepared to take on the Chinese Communist Party? Who will win the new Cold War against the CCP?

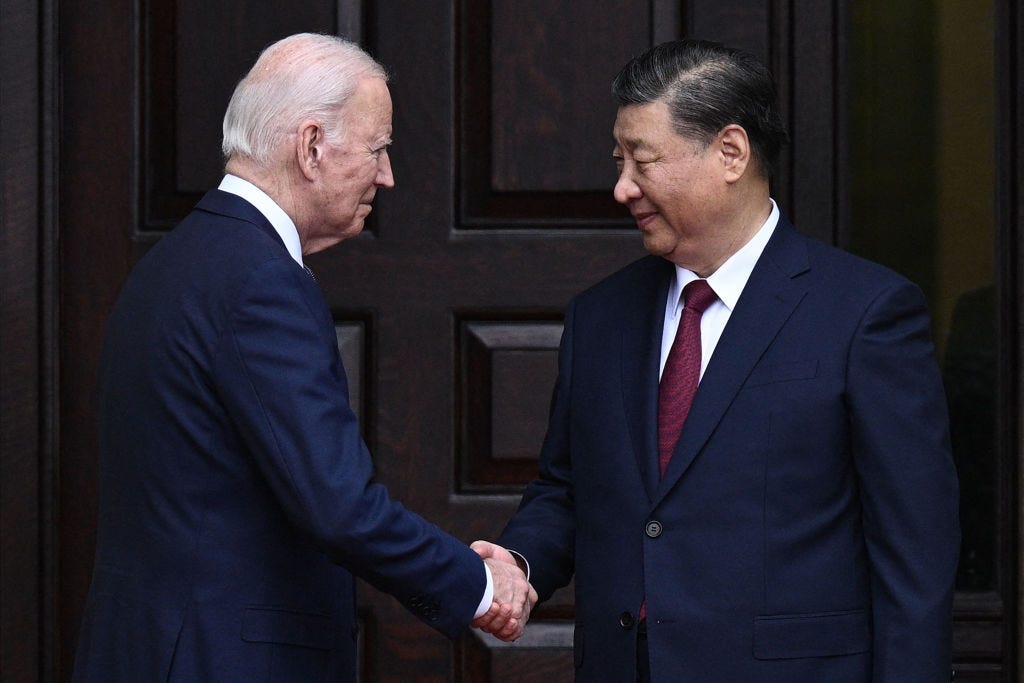

When it comes down to this fight between Washington and Beijing—a fight that began in earnest when President Trump imposed tariffs on Chinese goods in 2018—the Chinese have a heavyweight in their corner. But it’s not Xi Jinping alone; Xi has an important ally that makes the fight lopsided in China’s favor.

In one corner is the U.S., represented by President Biden. In the other corner is Xi, accompanied by corporate America—represented by Silicon Valley venture capital firms, New York private equity companies like KKR and Blackstone Group, and boundaryless, one-world corporations like Salesforce that all want a return to pre-2018 U.S.-China relations. It’s going to take all the strength and willpower the U.S. can muster to make this a fair fight.

It won’t be easy. A return to pre-2018 U.S.-China relations would be good for China and bad for the United States. It will be a disaster if these trade imbalances grow: A U.S. in a perpetual and growing trade deficit will have to keep borrowing money to pay for all of the imports coming into the country. But a nation cannot run up international debt forever. Foreign lenders will ultimately get worried about getting paid back, and that would trigger a financial crisis. Put simply, then, it is best we wind down these massive trade imbalances with China now.

Many in the C-suites of corporate America disagree.

A Standing Ovation for Xi

Everyone at November’s Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation conference dinner in San Francisco should have seen it. Xi Jinping told dinner guests—who paid a minimum of $2,000 to attend—that the U.S. should let bygones be bygones. He said, “China is ready to be a partner and friend of the United States.” In short, it seems like Xi wants to “hug it out” with the U.S.

But what does partnership and friendship really mean to Xi? It definitely means no more tariffs on Chinese-made goods as a punishment for intellectual property theft and 20 years of trade deficits. It means no more banning Wall Street from buying shares in dozens of Chinese companies linked to defense contractors. It means no more export restrictions on U.S. computer hardware going to China. And forget about America’s human rights concerns for Uyghur Muslims and the new U.S. legal bans on solar goods and clothing sourced from Xinjiang, where the Uyghurs live. The Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention law will be scrapped.

But how did the dinner guests respond to Xi’s speech? He was given a standing ovation. Tim Cook, the CEO of Apple, was there joining in the ovation. In fact, Apple paid $40,000 for a seat near Xi at the dinner. Ray Dalio, hedge fund manager to China at Bridgewater Associates, was also there. China is a very important client to the Connecticut-based asset manager. Larry Fink, the CEO of BlackRock, was there as well. All of these people agree with Xi that it’s time to hug it out. They want a return to the days when Chinese markets were opening to the West, when China was a place in which to invest in new startups.

Instead, large companies are disentangling themselves from China, though not because they want to. Apple, for one, says it will move some iPhone production to India because of geopolitical tensions. Apple would prefer to stay in China. It is going to be very costly for them to move, but politics makes it prudent. They wish it wasn’t that way. Like everyone else at Xi’s table, Tim Cook wants the pre-2018 years back.

However, at least two of Biden’s signature laws would become obsolete if this ever happened.

The Best Laid Plans May Go To Waste

Chip manufacturing has increasingly moved to Asia and particularly China, which is the biggest buyer of U.S. semiconductors. Over the last two years, the Biden administration has authorized the spending of $52.7 billion to bring semiconductor manufacturing back to the U.S. China has wanted U.S. companies to set up shop there instead. If China and the U.S. kiss and make up, why would Micron, a major U.S.-based semiconductor maker, spend $40 billion on a new fabrication facility here when it can spend a quarter of that on one in Guangzhou?

Additionally, the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act has set aside $500 billion in tax credits and other funding mechanisms for solar and wind technologies and electric vehicle batteries to be made in the United States. Billions of dollars have been invested here thanks to that law. But those plans would evaporate if those same companies could just import from China more cheaply.

As it is, many of the new EV battery factories being built in the U.S. because of the Inflation Reduction Act are Chinese. Gotion High-Tech is spending around $2 billion for a new factory in Michigan. CATL has partnered with Tesla. (Ford has its CATL partnership on hold because of political pressure.) Without the Inflation Reduction Act, China would keep its labor in its own country and ship the batteries here for final assembly. Ford would gladly import instead of investing in a new factory and paying (and fighting with) American unionized labor.

No ‘Win-Win’ Option for the U.S.

What would the U.S. get out of accepting the Xi peace offering? Silicon Valley would get to invest in new Chinese startups with the help of CCP insiders that give them knowledge on which companies the government is going to support. Wall Street would get its desired return to a pre-2018 world with no restrictions on capital flow to China. BlackRock, Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan and other investment banks have offices in China, hoping to expand their market share among the locals. If the U.S. and China are not best of friends, it makes it harder for them to gain traction in a country that perceives them as unfriendly.

If the China-U.S. relationship is no longer treading on thin ice, it allows for safer sledding for companies that have waited years to be in China. Naturally, those companies don’t want to lose that relationship because of a battle between Washington and Beijing. This is their view, of course, even if China will make certain that their local companies have a bigger market share at home than American ones.

This is what the U.S. is up against. It is fighting China and its own established corporate and investor interests at the same time. It’s two against one.

This year, the U.S. trade deficit with China will be about $100 billion less than the 2022 deficit, meaning we are buying less from China this year. This could be the start of a continuing trend. Not surprisingly, then, Xi obviously wants a return to the past. In addition to the shrinking trade deficit, his country is seeing less U.S. investment, and export restrictions on tech are slowing China’s progress in that space. U.S.-imposed tariffs have meant Chinese companies are now outsourcing to Vietnam, primarily, at great loss to blue-collar labor back home. It is important for China to reverse this trend, unless it can come up with a way to build its own consumer market to pick up the slack for what it sells to the U.S.

It is reasonable for Xi to ask for a “win-win” relationship of mutual respect, but in truth, there has never been a win-win option, at least for the U.S. The U.S. is a services economy, but our blue-collar labor force has suffered greatly in recent decades: Today, most of our services trade balance comes from foreign sources paying for Adobe Acrobat software licenses, Apple Store fees, flights to the U.S., undergraduate studies on American college campuses and, of course, U.S. stocks and bonds. For the industrial side of the economy, China has taken the place of our blue-collar workers.

This is apparent across many of our metro areas. Since 2001, the high-tech manufacturing towns of the Bay Area have lost 51% of their manufacturing jobs—94,000 jobs in all—due to imports from China. The hardest-hit metro in absolute terms is the Los Angeles metro area which lost 218,881 manufacturing jobs due to Chinese imports since 2001. The New York City metro area lost more than 130,000 jobs during that time, while the Chicago area lost more than 123,000 manufacturing jobs alone.

The unbalanced trade relationship between China and the U.S. is a problem for both sides, really. If we returned to pre-2018 trade, China—already the go-to American manufacturing center—would become ever more reliant on the U.S. to sell its goods. As long as foreign capital keeps flowing into China, this is good news for them. But it would mean the U.S. returns to its overdependence on China, lays off workers due to Asian outsourcing, and we watch American capital flow to the growth markets—in this case, to China and Southeast Asia as a whole. This is totally unsustainable.

Large imbalances are almost always caused by finance, industry or trade policies, writes Michael Pettis in his book The Great Rebalancing—and indeed, “many of the global and regional crises in the past two hundred years were driven by these imbalances,” he says. Section 301, 232 and 201 tariffs, the CHIPS Act and the IRA have helped stop the bloodletting. Hugging it out with Xi instantly makes it worse.

Just after the APEC dinner, cloud computing company Broadcom CEO Hock Tan—who was in attendance at the dinner—said that he would be cutting 2,000 jobs from Broadcom’s VMware divisions in California, Washington, Colorado and Georgia, following China’s antitrust agency’s approval of the $69 billion Broadcom-VMware merger. It is unclear if this work previously handled by these jobs will be outsourced to Asia ever, or if Broadcom will set its sights on China developers for the next big thing. Yet this is an important reminder of how China and many U.S. companies are on the same team.

If Washington ever puts outbound capital restrictions on private capital, it would be high risk for Broadcom or any private investor to consider China tech. Xi doesn’t want that—but neither do the investors who attended the Xi dinner. And for this reason, it’s clear that the same people who stood up for Xi will do so not only in San Francisco, but in Washington as well.