In Defense of “Workism”

The goal of public policy should be to help people find meaningful work, not to help them to drop out of the labor force

Beneath all the practical wrangling over government spending, public policy and the welfare state, there is often a hidden contest over values. In the case of the welfare state, it is a contest over the value of work.

That contest has come a little closer to the surface after nearly two years of pandemic relief and battles over the child tax credit. These new welfare state benefits, far from being tied to work requirements as in previous welfare reform efforts, were designed specifically for the purpose of keeping people out of the workforce in order to prevent the spread of COVID. Yet these emergency programs have been proclaimed as a great success in reducing poverty that should be continued indefinitely.

This raises a dilemma that goes back to the origins of our modern welfare state. When Lyndon Johnson unveiled his Great Society agenda back in 1964, he proclaimed that the goal was to enable the poor to “move with the large majority along the high road of hope and prosperity,” which implies that they would be out working and getting ahead. But in another speech that same year, he also denounced “unbridled growth” and “soulless wealth” and indulged in a lot of woozy flower-child talk about how we had transcended the need for “unbounded invention and untiring industry” and should focus instead on trying “to enrich and elevate our national life.”

A Swiss campaign a few years ago to promote universal basic income put this sort of thing a little more baldly in a giant poster which asked: “What would you do if your income were taken care of?” Note the passive construction to describe the fact that other people are working so you don’t have to.

That raises a basic question: Is the goal of public policy to get people to work—or to save us from the necessity of work?

All of this has come into focus in recent years in an attack on “workism.”

The “Meaning Crisis” Solves Itself

“Workism” was defined by Derek Thompson a few years ago in The Atlantic as “the belief that work is not only necessary to economic production, but also the centerpiece of one’s identity and life’s purpose, and the belief that any policy to promote human welfare must always encourage more work.”

This last point, pushing back against encouraging work, is where the rubber really meets the road, because it is part of the push to un-reform the welfare reforms of the 1990s, on the grounds that it is cruel and unjust to restrict welfare in a way that requires its recipients to work.

The argument against this emphasis on work is that it is a puritanical moral “obsession” arbitrarily imposed on people, and also that it is all a lie concocted to serve our corporate masters, because the majority will never actually find personal fulfillment in their work. Here is Thompson again:

But our desks were never meant to be our altars. The modern labor force evolved to serve the needs of consumers and capitalists, not to satisfy tens of millions of people seeking transcendence at the office. It’s hard to self-actualize on the job if you’re a cashier—one of the most common occupations in the US—and even the best white-collar roles have long periods of stasis, boredom, or busywork. This mismatch between expectations and reality is a recipe for severe disappointment, if not outright misery.

So you start out thinking you’re going to work to “follow your bliss,” but you just end up working to line the pockets of The Man.

Similarly, Tablet recently carried a broadside against work and career as a source of meaning specifically for women, lamenting that “pop-feminism has continued to lean into the corporate system, devaluing any life choice for women that does not center on economic prosperity.” This is either a radical leftist perspective, with all its railing against “the corporate system,” or a traditionalist-conservative perspective, with its talk about the previous generations of women “who were raised to become mothers and wives.” But who can tell the difference between left and right anymore?

The wider complaint is that we may have greater prosperity and be building and making more things—in other words, we may enjoy material progress—but we face a growing “meaning crisis,” in which we have no clue what gives value and direction to our lives or what can produce a sense of personal fulfillment and happiness. There are various people you can find on YouTube who will tell us how to fill this void with Buddhism, or psychedelics or Stoic philosophy. The fact that none of these solutions is particularly new—the hippies tried two of the three a half century ago—might cast a little doubt on whether this “meaning crisis” is really anything new or whether it is just the human condition.

To state the dilemma: How can we continue to create new wealth, invent new technology and advance human material progress, while also finding something that gives purpose, direction and meaning to our lives?

Put that way, the question kind of answers itself—and “workism” is the answer. Creating new wealth, inventing new technology and advancing human progress is something that gives purpose, direction and meaning to our lives. Or rather, “workism” is a pejorative term—an update of “workaholic”—used to dismiss what is actually a very compelling idea: that solving human problems, building the future and just plain getting things done is, in fact, an important and meaningful activity.

Howard Roark on the Meaning of Life

The obvious problem with the denunciations of “workism” is that work is an unavoidable necessity of life. If we had forgotten that, if we were tempted by fashionable notions that automation was going to take over human jobs and allow us all to live a life of comfort on a 15-hour work week—well, COVID was our wake-up call.

Under the rubric of protecting people from the pandemic, we temporarily created a welfare state designed to keep people from working, pulling millions out of the labor force. The result is a labor crunch, a supply chain crisis, widespread shortages and a rate of inflation at a 40-year high. Despite panicked predictions, for example, that truck drivers were about to be displaced by autonomous vehicles—something projected to happen as soon as two years into the future, six years ago—it turns out we still need a whole lot of truck drivers.

Work is not just a general necessity for the functioning of our economy, but is also crucial for the well-being of individuals. Derek Thompson blames “workism” for the fact that “America’s welfare system has become more work-based in the past 20 years,” as if we did it just out of a moralistic compulsion to smack people in the nose for being lazy. In fact, work requirements were intended to deal with one of the notorious dead ends of the welfare state: its tendency to lure its supposed beneficiaries into lives of dependency and stagnation, consigning them to a permanent underclass. To be removed from the world of work was to be left behind, warehoused in public housing and cut off from the “high road of hope and prosperity.”

But the necessity for work goes much deeper than that. Work and productiveness are the essential activities of human life, from which everything else flows. Every bite of food we eat, every stitch of clothing we wear, all the tools we use for travel, for information, for entertainment—none of it is provided automatically by nature. All of it has to be produced. That means, not just millennia of physical toil, but also millennia of discovery, invention and creativity.

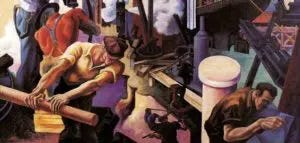

Gary Cooper as architect Howard Roark in the 1949 film version of The Fountainhead. Image Credit: Warner Bros./Wikimedia Commons

But how could this not be meaningful? How can mankind’s rise from the cave to the skyscraper—and our future rise to even greater heights—not be seen as something that contributes to our “personal identity and life purpose”?

Perhaps nobody represents this aspect of “workism” better than Ayn Rand’s hero from “The Fountainhead,” Howard Roark. Early in the novel, he explains the reason for his stubborn insistence on “my work done my way”: “I have, let’s say, sixty years to live. Most of that time will be spent working. I’ve chosen the work I want to do. If I find no joy in it, then I’m only condemning myself to sixty years of torture.”

Later, he goes deeper, making the case for work as central to the “meaning of life,” specifically in answer to “Those who seek some sort of a higher purpose or ‘universal goal,’ who don’t know what to live for, who moan that they must ‘find themselves,’” which “seems to be the official bromide of our century.” That’s from 1943. Like I said, the “meaning crisis” is nothing new.

Here is his answer, or rather Rand’s answer by way of her character.

Roark got up, reached out, tore a thick branch off a tree, held it in both hands, one fist closed at each end; then, his wrists and knuckles tensed against the resistance, he bent the branch slowly into an arc. “Now I can make what I want of it: a bow, a spear, a cane, a railing. That’s the meaning of life.”

“Your strength?”

“Your work.” He tossed the branch aside. “The material the earth offers you and what you make of it.” The flip side of finding meaning in work is finding work that deserves that meaning. It means, like Roark, finding work that interests you and that you want to do, rather than just ending up wherever life shunts you. But many more things can fall under that category than you might think.

“Finding your bliss” is a catchphrase associated with Silicon Valley entrepreneurs or white-collar workers in creative fields, and I supposed it is comparatively easy to find your bliss in a multi-million-dollar payout from a startup or in writing the Great American Novel. But the actual enjoyment of work is something I have observed most frequently in blue-collar workers who take pride in their jobs as plumbers, electricians, framers, carpenters. TV host Mike Rowe has built a whole empire out of this with his show, “Dirty Jobs,” which celebrates people who take pride in their willingness to do the smelly and seemingly unpleasant work that other people shy away from.

But this means being open to finding meaning in work that is valuable simply because, as Rowe’s show likes to remind us, “someone’s got to do it.” There is a definite and powerful meaning in being the kind of person who is willing to do what needs to be done, and white-collar “knowledge workers” who look down on these grubby necessities are merely revealing their blind spots.

The Contest Between Homer and Hesiod

Building and creating is the main business of life, not just for basic survival but for rising to higher and higher heights. I find it ironic in recent years that overwrought predictions about automation removing the necessity of work have been billed as “Star Trek economics.” Yet the characters in that franchise, particularly in its classic television installments, are notable for finding meaning and value in their work, what with all the exploring of strange new worlds and the thrill of technological problem-solving. Also consider the enormous amount of work still left for us to get anywhere near the technological utopia of the “Star Trek” future—something that will require a healthy dose of “workism” for centuries to come.

The role of work in human life is an issue that has drawn our attention since the dawn of civilization, particularly in an ancient Greek legend about the contest between Homer and Hesiod, the two greatest poets of their era. Homer composed great epics about war and adventure, while Hesiod’s most famous poem, “Works and Days,” is a kind of ancient “Poor Richard’s Almanac,” full of advice about how to run a farm—a mixture of practical tips and hard-earned life wisdom.

In the legend, Homer and Hesiod end up in the same city and are summoned for a contest. Homer clearly emerges as the better poet, but the king gives the prize to Hesiod anyway, “declaring that it was right that he who called upon men to follow peace and husbandry should have the prize rather than one who dwelt on war and slaughter.”

That raises the question: What are the alternatives to finding meaning in work? In the cultural expressions of “workism,” “Star Trek” offers us explorers, scientists and engineers as heroes; “Dirty Jobs” offers us grimy sewer cleaners and welders; Ayn Rand made heroes out of architects, scientists, inventors and industrialists. What are we offered if we reject that?

To find meaning in work, even in obsessive work, does not mean that you can’t also find it other places, such as family or art—and I can vouch for that from personal experience. And work can take non-commercial forms, particularly raising children. But what about a life without any work at all?

Derek Thompson notes in passing the actual model: “The landed gentry of preindustrial Europe dined, danced, and gossiped, while serfs toiled without end.” Serfdom ended many centuries ago, but think of the characters in a Jane Austen novel, who occupy themselves with the leisure pursuits of a “gentleman” class that only exists because of their inherited claim on an income provided by those who did the work but didn’t get novels written about them.

Alexis de Tocqueville noted this difference in attitudes between Americans and Europeans. For the Europeans, work was literally ignoble: What distinguished you as a member of the nobility was precisely that you did not have to work. In theory, this freed up the leisure class for a limited number of pursuits considered respectable: science, art, religion, politics and war. In practice, aristocrats were notorious for devoting their time to less elevated activities like playing cards, gambling on horse races and sexual intrigue. In the more genteel version, courtesy of Jane Austen, you will notice that most of the drama still centers around economics—but instead of working for the money, our heroines have to marry for it, and money always threatens to be more important than love.

All of which is to say that there are far less appealing things than work that can serve as sources of meaning in life, or as a substitute for it. Did I mention war and politics as supposedly respectable pursuits, in place of earning a living? That is precisely what many young people are doing today, with culture-war posturing serving as a substitute for actual achievement as a way of conferring status and meaning.

Too Much Venting and Not Enough Inventing

A recent article in The Atlantic notes this trend and laments that “America has too much venting and not enough inventing.” The author goes on to call for an “abundance agenda” to address a national “scarcity crisis” and “increase the supply of essential goods.” That agenda will mostly involve getting a lot of people to go enthusiastically to work.

The author is Derek Thompson—the same Derek Thompson who lamented the scourge of “workism” a few years earlier and is now, in effect, prescribing it as the cure for our problem.

That’s a bit of a turnaround, but it’s no surprise. Work is a central activity that occupies our lives out of necessity, and most of us manage to find significant meaning, value and pride in doing it. “Workism” is neither a recent invention nor a weird theory. It is the actual reality of much of human life. We would be a lot better off acknowledging and embracing it.