Ignoring a Tradition That Goes Back to Washington, Some Military Officers Are Crossing a Dangerous Line

By Thomas Shull

This year has witnessed what United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres has called “an epidemic of coup d’états.” Since February, military coups have thwarted the transition of civilian-military regimes to civilian rule in Mali, Myanmar and Sudan. Meanwhile, military coups in Chad and Guinea have unseated corrupt but nominally democratic governments.

Americans usually file such incidents under Business as Usual in Former Third World Countries, taking for granted the U.S. military’s long-standing dedication to civilian rule and its subordinate role in our government. This faith isn’t misplaced: After all, in the more than 245 years since its founding, the U.S. military has never overthrown an American civilian government. Indeed, just last year, the military’s top official, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, unequivocally reaffirmed the principle of civilian control to Congress.

Unfortunately, he did so in reference to the upcoming 2020 elections—something that it is hard to imagine a military official having to do in decades past, before our escalating culture wars. But it was a prescient move given that after the elections, some of then-President Donald Trump’s past advisers openly began discussing U.S. military involvement to resolve their disputes.

The aftermath of the 2020 elections shows that perhaps we cannot take the military’s spirit of deference to civilian rule for granted. Sustaining this tradition, which traces back to America’s birth, requires attention. In this light, it’s worth revisiting a pivotal event in U.S. history—a moment of truth that took place in March 1783 and helped launch American military deference for generations to come.

A Crisis Averted

The British had surrendered at Yorktown some 17 months earlier, effectively ending the combat phase of the Revolutionary War. As peace negotiations ground to a close, a discontented Continental Army waited, encamped near Newburgh, New York. Not for the first time, the soldiers’ and officers’ pay was months in arrears, and the Confederation Congress still had not appropriated funds for the officer pensions it had approved more than two years ago. Worse, Congress had failed to act on a desperate petition from the army’s officers some weeks before, in late December 1782. By March, with a peace treaty expected daily, these officers were acutely aware that if they didn’t press their case now, they might never see the money they were owed.

On March 11, an anonymous letter from “a fellow-soldier” circulated throughout the American camp calling on the officers to inform Congress in no uncertain terms that the army had the upper hand. If peace were declared without the soldiers’ receiving redress, the army would refuse to disband and would retain its weapons. If, on the other hand, the war were to recommence, the army would head to the wilderness, leaving the country—and Congress—to the British.

This proposal is shocking in retrospect, but it’s easy to sympathize with the officers’ plight. The soldiers had repeatedly gone without pay and provisions under brutal conditions. Yet even so, they had risked their lives and won the war. No one disputed that they were owed the money, and many now faced poverty and uncertain prospects at home, surrounded by prosperous people they had defended.

When George Washington, then still commander in chief, learned of the letter, he acted decisively. He was deeply conscious of the justice of the officers’ complaints, and he feared their grievances would drive them to mutiny and risk the free government they’d fought for. In a dramatic confrontation with the officers on March 15, he alternately remonstrated, sympathized, pled and reasoned with them, making clear the disastrous course they were on.

“This dreadful alternative of either deserting our country in the extremest hour of her distress or turning our arms against it,” he observed, not only was “shocking,” but offered choices that were clearly “impracticable in their nature.” Congress, the civil authority, was “the sovereign power of the country,” and “discord and separation between the civil and military powers” held “ruin” for both the army and the country. He implored the men, “as you value your own sacred honor, as you respect the rights of humanity, as you regard the military and national character of America,” to reject “the man who wishes, under any specious pretenses, to overturn the liberties of our country.”

In effect, he argued that in this case, moderation in pursuit of justice was a virtue because it sustained a bedrock principle of liberty: the military’s subordination to civil authority. Risking a gross injustice was better than risking the hard-won freedom they’d fought for.

By the end of this emotional appeal—some of the men wept—the mutiny was averted. Indeed, the officers passed resolutions expressing their continuing trust in Congress. These declarations were published to widespread acclaim, helping an American citizenry suspicious of standing armies to imagine a military that could refrain from attempts to seize power.

One General Draws the Line; Another Crosses It

The U.S. military now remains one of the few American institutions still popular with the American people, and the military itself is committed to an “apolitical” code of conduct meant to ensure it never interferes with civilian rule. This commitment was reaffirmed last year prior to the presidential election when the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, U.S. Army General Mark Milley, responded to inquiries from Congress by writing that with elections, “by law U.S. courts and the U.S. Congress are required to resolve any disputes, not the U.S. military. I foresee no role for the U.S. armed forces in this process.”

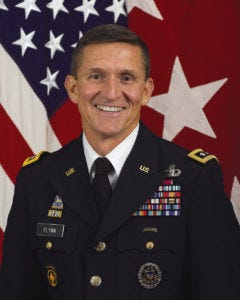

As chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Milley spoke with authority. But another high-profile general weighed in on the issue as well: retired U.S. Army General Michael Flynn.

Gen. Michael Flynn. Image Credit: Defense Intelligence Agency

Flynn, a former director of the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency, is most widely known for having resigned just weeks into his tenure as former President Donald Trump’s national security adviser following claims that he had lied to the FBI and to Vice President Mike Pence—an affair that led to tortuous legal proceedings and ultimately to Flynn’s receiving a presidential pardon. In December 2020, as President Trump questioned the election’s results, Flynn argued on Newsmax TV that President Trump could declare martial law and have the military supervise a rerunning of the presidential election in “swing states.” Earlier that month, Flynn had retweeted a news release from a group calling for “limited martial law” to allow the military to oversee a new election “if Legislators, Courts and the Congress do not follow the Constitution.” Flynn added, “Freedom bows only to God.”

But therein lies the rub; for if the goal is freedom, how is it achieved? Washington’s stand at Newburgh was informed by the recognition that fundamental to freedom—to “the liberties of our country”—was the primacy, the sovereignty, of civil government. A pressing question of obtaining justice from Congress for his own comrades in arms should be left to its proper sphere: civil government.

Surely the same is true in elections, which are governed by extensive civil processes. These processes may be subject to human error and human vice, and they can certainly be messy—the 2000 presidential election comes to mind. But military processes are subject to human error and human vice as well, and it’s not hard to imagine how letting presidents, who are military commanders in chief, order the military to supervise elections in which they themselves are running could lead to abuses and even broader skepticism about the outcome. At the very least, it would create the appearance of a conflict of interest.

As at Newburgh, the risk of an unjust outcome through a civil process is better than the risk to a core principle of a free society. If reforms are needed, they can come through civil government. This point is worth reiterating in our era of deep cultural and political divisions, where questions of justice on both sides of those divides have sparked riots in the streets. Members of the armed services may be somewhat insulated from these passions by the military’s professional culture, but service members are still part of American society, and they care about justice too.

Which brings us back to General Flynn, whose comments have not been typical of the military’s apolitical approach—an approach to which prominent military leaders have called on retired officers to adhere as well. Indeed, in August 2020, The Washington Post reported that Flynn had been urged to moderate his language by former military colleagues, including retired Admiral Michael Mullen, a past chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who told the Post, “For retired senior officers to take leading and vocal roles as clearly partisan figures is a violation of the ethos and professionalism of apolitical military service.”

Wading Into Politics

Yet Flynn’s comments may be less an outlier than a bellwether—a sign of more strain on the military’s apolitical ethos to come. A 2009 survey by U.S. Army Colonel Heidi Urben of more than 4,000 Army officers (excluding generals) found that 81% agreed that “retired officers should be allowed to publicly express their political views just like any other citizen,” while 68% agreed it was “proper for retired generals to publicly express their political views.” These sentiments suggest a likely conflict with Admiral Mullen’s statement—a disconnect that may become particularly acute if retired generals continue to play a more prominent role in presidential administrations than they have in the past. Trump filled key cabinet positions with retired generals, and both he and President Joe Biden departed from tradition and obtained congressional waivers to appoint recently retired generals as secretaries of defense.

More surprisingly, the same survey found that 36% of the Army officers agreed that not just retired members, but even “members of the active duty military should be allowed to publicly express their political views just like any other citizen.” That officers would give this latitude to current service members suggests a direct failure to inculcate an apolitical ethos.

And pressure on that ethos has likely escalated with the rise of social media. A 2015-2016 survey of cadets at West Point and of military officers attending the National Defense University found that 50% reported that their active-duty friends “use or share insulting, rude, or disdainful comments” on social media about politicians running for office; the figure was 51% for their retired-military friends. Startlingly, 34% said their active-duty friends, and 47% said their retired-military friends, posted similar comments about the president—the commander in chief—a clear breach of military norms.

To be sure, there are legitimate questions about the feasibility and effectiveness of the military’s ethic of apoliticism, but some kind of ethic is still needed to ensure, among other things, its subordination to civil authority. Signs the ethic is weakening require attention by the top brass, either to strengthen the ethic or to implement a different approach that achieves the same goal.

This is not to suggest a military coup lies around the bend. But a sober view shows a military coup didn’t stand a chance in 1783 either. A stubborn and sprawling American populace had prevented the British military—then the strongest on earth—from imposing its will; the Continental Army wasn’t likely to do better. Nevertheless, without Washington’s timely intervention, the Newburgh conspiracy could have produced a substantial mutiny among the officer corps and a clash of arms that would have tarnished the army in the eyes of the American people and their civil leaders. Our current confidence that coups “only happen elsewhere” would, at the very least, carry a spiritual asterisk.

This sort of blot, rather than a coup, would be the more plausible concern in the military today. Perhaps it’s a rash remark by a serving general or a local commander stationed in a swing state at election time; perhaps it’s an ill-timed criticism or expression of support of a president who is being impeached; perhaps it’s news that a unit of soldiers refused to obey orders on grounds that they were disloyal to the president. This sort of public incident, clash or overstepping, having drawn on America’s culture wars, would set them further aflame and shake popular faith in a military that, unlike so many others in the world, rightly enjoys the confidence of the people it serves. A diminishment of the Newburgh legacy would be a painful casualty of the culture wars and a damaging inheritance to leave to America’s future generations, who may find themselves paying more attention to news about military coups than our generation has ever done.

This piece also appears on The UnPopulist, a Substack newsletter by Shikha Dalmia, a visiting fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. The UnPopulist is devoted to defending liberal and open societies from the threat of rising populist authoritarianism. Go here to subscribe.