Human Challenge Trials Are the Free Market

The free market is a free Marcus

By Daniel Klein

Human Challenge Trials would vastly speed up the development of a COVID-19 vaccine because subjects would receive not only the experimental vaccine but also the virus.

With standard trial procedure, those given the experimental vaccine have not necessarily even been exposed to a virus in the first place. They live their ordinary lives while researchers check on whether those individuals are exposed to the virus and then see how they fare. Human Challenge Trials speed things up: subjects are deliberately infected. It calls for brave individuals to step forward. It also calls for dramatic liberalization of how we test vaccines.

Human Challenge Trials relate to one of the great stories of ancient Rome. As the popular history website, History Heritage, explains:

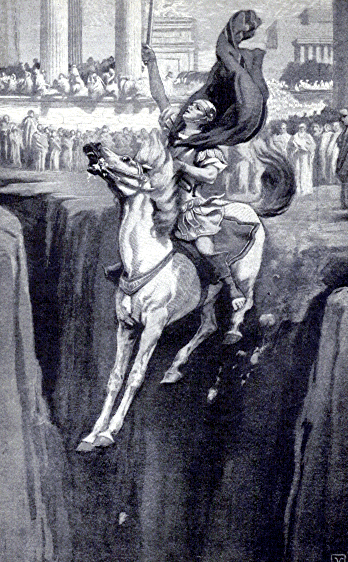

Marcus Curtius was a youth who had won great renown in war. When a deep crevice opened up in the Roman Forum, the seers declared that the pit would stay open until Rome threw into it its most valued possessions. Curtius put on full armor, and declaring that Rome had nothing of more value than its brave soldiers, mounted a horse and charged into the pit, which closed up soon after.

The free market is a free Marcus.

Like Marcus Curtius in Rome, America has no lack of brave soldiers willing to test early COVID-19 vaccines.

Free marketeers often talk about “the unseen” and “the invisible hand.” But when our eyes all move together, we see together, and we feel an effervescence (as Emile Durkheim put it). The importance of things little known suddenly comes into focus for the whole community.

The COVID-19 crisis makes our eyes move together and toward the center and central authority. Many look to the center for help and rescue. But we also see how government restrictions can kill us. An awareness of this truth has prompted many of the rules and regulations in the United States—400 and counting—to be waived during the crisis.

Adam Smith generally condemned “consumer protection” restrictions. He described one sort as being “as impertinent as it is oppressive.” But oddly enough, Smith made an exception to his own “liberal plan” when he endorsed the cap on interest rates. It has been suggested that Smith’s heart was not in it—that he picked his battles to avoid appearing rationalistic and militant about liberal principles. The interest rate restriction was long-standing and had religious overtones.

Perhaps Smith was throwing a fat pitch for someone else to hit out of the ballpark. That is exactly what Jeremy Bentham did. He quoted Smith’s words against him to advance his own free market conclusion.

Smith had lamely argued that if interest rates were not capped, too much money would be lent to wild-eyed “projectors” chasing impractical schemes; resources would be squandered. Bentham said the conclusion was unfounded. He concluded that the restriction was as impertinent as it was oppressive. (I believe that Smith privately smiled on Bentham and had quietly subverted his own reasoning.)

Bentham pointed out that established trades were once untested “projects,” and it is only by letting people take risks that the experiment happens and discoveries are made. Such discoveries may be boons to humankind—a “public good,” a “positive externality.” Such boons flow from the discovery process of free enterprise.

There is a glory due to bold inventors and other enterprising “projectors.” But it is a glory that many regard with jealousy.

Bentham himself personified individual projection, even to a fault. Yet I salute his glorious critique of Adam Smith on interest-rate caps.

Bentham wrote:

The career of art, the great road which receives the footsteps of projectors, may be considered as a vast, and perhaps unbounded, plain, bestrewed with gulphs, such as Curtius was swallowed up in. Each requires an human victim to fall into it ere it can close, but when it once closes, it closes to open no more, and so much of the path is safe to those who follow.

Bentham pointed out that even if most projects end in ruin, the legislator could nowise “derive any sufficient warrant...for wishing to see the spirit of projects in any degree repressed.” In other words there are both economic benefits and important moral consequences from allowing people to act freely, even to emulate Marcus Curtius:

To tie men neck and heels, and throw them into the gulphs . . . is altogether out of the question.

[B]ut if at every gulph a Curtius stands mounted and caparisoned, ready to take the leap, is it for the legislator, in a fit of old-womanish tenderness, to pull him away?

Laying even public interest out of the question, and considering nothing but the feelings of the individuals immediately concerned, a legislator would scarcely do so, who knew the value of hope, ‘the most precious gift of heaven.’

Thus did Bentham draw out the lessons of Smith’s liberal teachings.

As I write this, 8,219 brave souls stand mounted and caparisoned, for Rome, as it were, or God, or the creatures God loves. I refer to those who have registered their names for inclusion in Human Challenge Trials at the website 1DaySooner, to speed COVID-19 vaccine development.

But these great individuals are private enterprise. And yet, they are being pulled down by government restriction and jealous souls – restrictions and jealousy that are harming us now and that have been harming us all along.

A free market would mean free Marcuses, with just glory to those who put themselves on the line in bold actions that promise a boon to humankind. Come to think of it, what they are trying to volunteer for is not a bad description of the free market: “human challenge trials.”