How To Get Rid of a Tenured Professor

Activists push an apocalyptic vision of climate change, but that's not the scientific consensus. I got in trouble just for saying that

Who is the only person to appear in both the hacked 2009 Climategate emails and the stolen 2016 Hillary Clinton Wikileaks emails?

That would be me. Both cases exposed efforts to censor my research and damage my career at the University of Colorado Boulder. And in each case I thought, “Thank goodness for tenure and academic freedom!”

These days, I have less confidence in academic freedom. In December, at age 56, I left the University of Colorado after 24 years as a tenured professor, spending much of that time focused on climate change. In the 10 years before my departure, I was investigated, bullied and shunned to the point where leaving the university—once unthinkable—became inevitable.

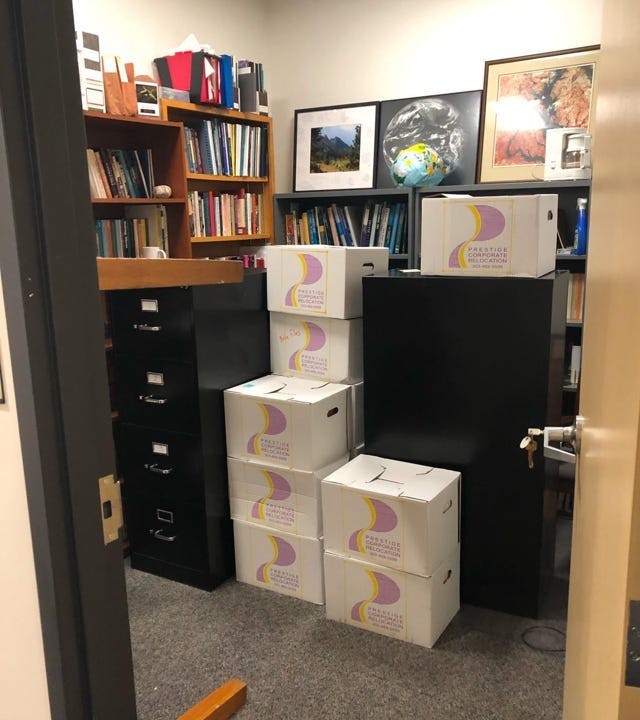

Colorado shut the science policy center I started and led, and canceled the graduate classes I developed and oversaw. It moved me to a tiny “office” that was actually a storage room and then commandeered the space to store boxes and empty filing cabinets. Later, it moved me to an office in the football stadium that was inaccessible for months. Finally, it refused to place me in any department, so I had no classes to teach.

During these years, climate change became a deeply politicized issue on campus. A cadre of faculty worked to transform the university into an activist organization dedicated to pursuing a left-wing agenda. This is antithetical to the traditional mission of a university to research, debate and teach in a forum tolerant of different opinions. It was even more disturbing that this was happening at a flagship state institution, one with a student body of more than 38,000 and ranked as a top 100 national university by U.S. News & World Report.

My experience isn’t unique. Colorado administrators have punished other faculty and cut back their roles. In fact, 7% of faculty polled said they had been disciplined or threatened with discipline because of what they were teaching, researching or saying in talks both on and off campus, according to a survey published in December by the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression. Almost a third of the university’s faculty believe that academic freedom is “not very” or “not at all” secure on campus.

Of course, highly political campuses are a nationwide plague. Among FIRE’s survey of 6,269 faculty at 55 major colleges and universities:

Nearly half of conservative faculty said they can’t voice their opinions because of how others might react, compared with less than a fifth of liberal faculty.

More than a third of faculty said they self-censor their written work. That is nearly four times the number who said this in 1954 at the height of McCarthyism.

Some 87% of faculty said they find it difficult to have an open and honest conversation on campus about at least one hot-button political topic.

For those unacquainted with how intolerant academia has become, I might seem like an unlikely candidate for cancellation. I’m a sharp critic of Donald Trump, and I voted for Hillary Clinton, Joe Biden and Kamala Harris. I have never questioned that global temperatures are rising, that man-made emissions are a major contributor to this increase, and that we must cut our dependence on fossil fuels.

My sin is sticking to science, but climate activists, including many professors, don’t always like what the science actually says. My research is part of a broad consensus in scientific literature that the evidence of climate change raising the number or intensity of hurricanes, tornadoes, floods and other types of extreme weather is incredibly weak. (There is solid evidence, however, of more heat waves and extreme precipitation.) The overwhelming reason for the rising cost of natural disasters is that more people with more wealth and more valuable property live in locations exposed to extreme weather, not an increase in extreme weather itself.

Most people are surprised to learn this because that’s not what they hear from politicians and much of the media. But the broad consensus—under the auspices of the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change—has been an inconvenient truth for activists, journalists and government officials who insist on misrepresenting IPCC assessments and making apocalyptic claims about extreme weather. We saw it in January with climate change getting the blame for the deadly Los Angeles wildfires despite the absence of any evidence. I’ve been a critic of this hype and so I’ve long taken incoming from activists. Nowhere did I become a bigger target than on the campus of my own university.

My Troubles Begin

Everything for me changed in February 2015, after Rep. Raul Grijalva (D-Ariz.) asked my university to investigate me, and it agreed to do so. The Obama White House had criticized my testimony to a U.S. Senate committee summarizing what the IPCC said about natural disasters. Grijalva accused me of secretly taking money from Exxon in exchange for what I told Congress. (He also asked six other universities across the country to investigate members of their faculty.)

So began years of disruption to my career and personal life. I was disinvited from just about every talk that I had been invited to. Some colleagues stopped collaborating with me; one explained, “I wish I could help, but I don’t want them coming after me.” Reporters stopped calling and a program officer at the National Science Foundation told me not to bother submitting any more grant proposals there; I was just too controversial. What’s more, I learned that university support for the science policy center I had been recruited to start in 2001 might no longer be guaranteed. Meanwhile, no administrator ever spoke to me about the investigation, not even to check in and see how I was doing; I heard only from university lawyers.

Of course, I was not taking anyone’s money in exchange for testimony or anything else, as the investigation concluded a year later. But by then Grijalva and everyone else had moved on. The allegation, however, had lasting consequences, so mission accomplished. The announcement of the investigation had made The New York Times and my local newspaper; its resolution did not.

So, I decided to leave the policy center and its umbrella environmental research institute. My idea was to start a sports-governance center, and thanks to the enthusiastic support of the athletic director, the university allowed me to move across campus and join the athletic department. The new center would focus on another one of my passions, far from the reach of the climate police. My hope was that once I was gone from the science policy center, the administration wouldn’t close it.

For four years things were great. I developed and taught a popular undergraduate class, worked with colleagues on a proposal for a professional master’s degree, and helped produce ground-breaking research. The governance center received national and international attention; U.S. soccer Olympian Hope Solo, disgraced cyclist Lance Armstrong and others dropped by the class to visit with students.

Meanwhile, back on the other side of campus, faculty and administrators began rushing the university headlong into climate advocacy. In 2016, the faculty’s main governing body, the Boulder Faculty Assembly—led by a professor from my previous department, environmental studies—adopted a gratuitous statement “to confront and support solutions … to address the effects of changes to our global and regional climates.”

(I’m not naming anyone at Colorado in this account. I’m describing an institutional failure as seen from my perch. Sure, institutions are led by people, but the failures here were systemic. Any of more than two dozen administrators could have easily addressed these issues. None did.)

Activist faculty members were just getting started. Over the next seven years, the faculty assembly issued eight statements and resolutions calling for climate advocacy on campus that included encouraging students to engage in nonviolent “confrontations” and joining with outside groups to declare a “climate emergency.”

All of this might have been laughed off as a handful of self-important professors trying to save the planet one resolution at a time. Soon, however, the empty exhortations turned into demands that the entire university morph into a climate advocacy organization. In 2023, the activist professors pushed through a resolution urging the university to make climate activism “the central focus of our campus-wide initiatives.”

This new focus included a demand that “all CU departments and units” (emphasis in original) create climate courses “that will prepare our graduates for employment as climate solution leaders in their respective fields.”

The resolution also demanded that “faculty, students, staff and administrators unite into a powerful cohort that advocates for and takes significant action toward reducing … emissions—across the campus, community, state and nation.” And it urged “policymakers, including the regents, administrators and campus leadership, to implement swift and systemic changes in order to avoid the worst impacts of extreme weather events, the devastation of human habitats, the collapse of ecosystems, and the loss of biodiversity.”

This reads more like the mission statement for Greenpeace than something issued by a flagship university. Imagine if the entire faculty decided to declare that Colorado’s mission was to advocate for deporting undocumented immigrants or banning abortion, and that all teaching and research should fall in line with these political aims. That would be crazy, right?

Along the way, the resolutions got some muscle. In 2020, the university launched the Center for Creative Climate Communication and Behavior Change, which focused on “changing human … attitudes, beliefs and behavior that will meet the climate challenge,” including changes “to individual consumption.” The leaders of the center were some of the professors behind the faculty assembly statements rallying the campus to climate advocacy, including the environmental studies chair.

In 2022, responding to faculty demands, the university hosted a climate advocacy conference—the Right Here, Right Now Global Climate Summit. The emphasis was on exhortations to political action from celebrities such as Barbra Streisand, Neil Young and Ziggy Marley. There was no connection to the university’s actual mission—to teach students how to think, not what to think.

While the university was turning up the dial on climate activism, changing the institution in the process, I was busy teaching and researching sports governance. I was generally unaware of how climate advocacy was becoming core to the university’s mission. Then, for reasons never made clear to me, the successful experiment in marrying academics and athletics ended; after four years, Colorado decided to stop developing the sports-governance program.

Piling On

It soon became apparent that the university would hound me until I quit. It couldn’t fire me because I had tenure, but it certainly could make life uncomfortable. Rather than return me to the environmental research institute (as was promised in the memorandum of understanding that transferred me to CU Athletics), the administration put me directly under the environmental studies department and doubled my teaching load from what was stipulated in my original contract.

For an office, the department gave me a small, windowless room previously used for storage. It did not give me a telephone, computer or mailbox, and I was far removed from the department’s office and the other faculty. OK, I thought, I’ll make this work. I set up shop in the storage closet and committed myself to keep conducting excellent research and teaching excellent classes.

In 2020, the university finally closed the science policy center I had left in 2015. Then it decided that it would no longer award the graduate certificate in science and technology policy I had established. The climate-campaigning chair of my department was involved in both decisions. Next on the chopping block: the eight graduate courses that were central to my teaching portfolio—they would no longer be offered.

To revive the science policy center, I volunteered to take complete responsibility for it. I even found an outside partner to help fund it. And I offered to oversee the graduate certificate program again. But the environmental studies chair told me: no, absolutely not, he would not allow it. He seemed dedicated to ridding CU of this pesky professor.

My original contract with the university specified that I focus on teaching graduate courses and developing new ones. But now I was repeatedly told to develop and teach new undergraduate courses. One was a fun and popular energy policy course that received rave reviews from students. After the class size tripled in just two years, I was permanently removed from teaching it.

Nevertheless, I decided to hang in there. I wanted to stay in Colorado—my family has deep roots in the state—and before too long I would be 55 and eligible to retire.

Not long after moving into my windowless “office,” the university decided to store a large number of boxes and several filing cabinets there, making it unusable. I never touched them, mainly out of fear that I’d be accused of something nefarious. Later I learned that the filing cabinets were empty. Funny!

By now the pandemic was underway and everyone was working remotely. Having an office was not that big of a deal. But after we returned to campus, I mentioned the unusable office to anyone who would listen, asking that the situation be fixed. Many colleagues were sympathetic, but my department chair did not budge.

Instead, he placed me under investigation. Yes, another investigation! Bizarrely, he accused me of violating university procedures in winning a grant. I don’t know how it’s possible to get a grant outside of university procedures, so the accusation was obviously a sham. Honestly, if you want to investigate a colleague and need to conjure up a false accusation, there are more creative ways to do it.

The investigation spanned almost a year. My chair empaneled some of his cronies to write a report. He found me guilty of something or other and sanctioned me, which I guess was just a strongly worded letter in my file.

But he did throw around phrases such as “possible termination,” and administrators acted like they were taking it seriously, so I took it seriously as well. I appealed to a faculty committee outside my department, which found no basis for the investigation and that my due process rights may have been violated. The sanction was overturned. My chair suffered no consequences for making the false allegation.

Next up, I was hit with an official inquiry because I allegedly violated university policy by telling colleagues about the sham investigation. The inquiry was apparently instigated by a faculty member at the “behavioral change” climate center. I have no idea what became of it.

As this campaign of harassment played out, I asked administrators many times to either order a formal process of mediation with my chair or find me a new home on campus where I could escape my hostile work environment. Administrators did neither for three years.

Finally, in the fall of 2023, a new dean of arts and sciences I’d never met moved me out of my department. But he didn’t put me in a new one, which meant I would have no classes to teach. I contacted many departments to ask about joining them, and some showed interest. But with no administration backing for finding me a new home, I had no luck.

I was, however, given an office—with a window!—in the football stadium, which already housed an island of misfit toys’ worth of academic programs. My new office, though, came with a catch: It became inaccessible a few months later when work began on installing a gigantic video screen at one end of the stadium, directly over where I was situated. I got several days’ notice right before Christmas and was not given another space.

So, at the start of last year, I found myself with only one leftover course to teach and no office. And I had no way to pursue grants for research or to recruit graduate assistants. I figured Colorado was now ready to oust me by claiming that I was not fulfilling any job duties, even though it had made that impossible.

I considered just going with it: collecting a paycheck with no obligations. There’s probably a joke here involving Seinfeld’s George Costanza and his “job” at the New York Yankees. Instead, years after Rep. Grijalva demanded that the university investigate me, I finally took the hint: The administration did not want me around, and it was going to turn the screws until I left.

So, having reached age 55, I told the university I would retire at the end of 2024. And I am glad I did, not just because of what I’m leaving behind, but also because of what lies ahead. I joined the American Enterprise Institute as a senior fellow, and a faculty committee at Colorado approved my request to be an emeritus professor.

But amid this happy ending, my story contains stark lessons. First, academic freedom and tenure mean little without administrators who stand up for faculty members when they are under attack—whether from inside or out, whether from the left or the right. Also, when a university institutionalizes political advocacy, it grants a green light for faculty and administrators to go after colleagues they view as political enemies and to abuse the university’s policies and procedures in doing so.

I retired from Colorado, however, with many good memories and a strong sense of accomplishment. I had many wonderful colleagues and collaborators. I especially enjoyed the students. I never once had an issue with them. They welcomed our discussions of complex issues, whether climate change or transgender athletes. My experience is that the students are far less interested in politicizing the campus than the faculty is.

I expect that at Colorado, the fever of climate advocacy will break at some point and science-backed views such as mine might again be welcome. So, I don’t really feel like I’m leaving the university—the university left me.

Roger Pielke, Jr. is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and an emeritus professor at the University of Colorado Boulder. He is one of only a few researchers whose peer-reviewed publications have been cited in all three working groups of the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. His books include “The Rightful Place of Science: Disasters and Climate Change"(2018).

A version of this article was originally published on Pielke’s Substack, The Honest Broker. Readers can subscribe here.