How Portraits Can Change Immigration Policy

By Liya Palagashvili

In the summer of 1995, my family and I landed alongside the Amish in rural America after living through five years of war, blockades, and economic and political turmoil following the collapse of the Soviet Union. We found shelter in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, and were greeted by the generosity of the Mennonite community, our sponsors who helped us settle into an unknown world. Building a new life from scratch—and with no family, friends or familiarity with the language or culture—is an experience that is simultaneously unique and yet shared by all immigrants across societies and time.

Twenty-six years later, I relived my immigration experience through the unique stories and portraits of 43 American immigrants, painted by former U.S. President George W. Bush in his latest book, “Out of Many, One: Portraits of America’s Immigrants.” This timely book provides a breath of fresh air—a humanizing voice of reason on immigration—that stands in contrast to the often-extreme voices that dominate the national discourse. This is precisely the beauty of the book: It interweaves the personal stories of immigrants with a sensible approach to U.S. immigration reform.

The emotional yet uplifting stories highlight the values ingrained in these distinctive individuals—resilience, courage, gratitude and generosity. They also have shown an unwavering commitment to America and to make the most of every opportunity in America. Across every story, three stand out as distinctive elements of the U.S. immigrant experience: civil society, opportunity and entrepreneurship.

Immigrants and Civil Society

First, a thriving American civil society features prominently in the book. The individual stories of immigrants center on the nonprofit organizations and religious institutions that helped bring them to or settle them in the U.S., as well as the “random kindness” of strangers, teachers and coworkers.

Joseph Kim, who lived through the unthinkable in North Korea, escaped to China and then found refuge in the United States with the help of the nonprofit organization Liberty in North Korea, as well as Catholic Charities, which found him a foster home and supported him upon his arrival.

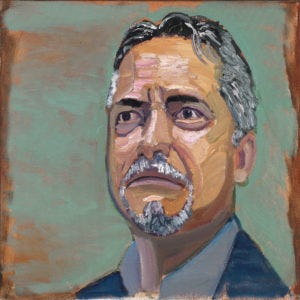

Portrait of Carlos Rovelo by President Bush. Image Credit: George W. Bush Presidential Center

Carlos Rovelo was forced by civil war in El Salvador to leave his family behind and come to the U.S. as a student. He soon reunited with his family thanks to the First Presbyterian Church, which undertook the entire immigration process and costs and supported Carlos’ family upon their arrival. Carlos explains, “The church practically adopted my family. . . . [They] provided us with an apartment, furnishings, and food. . . . We will forever be indebted to the families of this church who so lovingly cared for us.”

Almost two centuries ago, Alexis de Tocqueville wrote in “Democracy in America” about a flourishing civil society rooted in civic participation and civic associations. Political scientists such as Robert Putnam and Elinor and Vincent Ostrom have long identified civil society as the backbone of American “greatness.”

But what struck me the most is how many of these immigrants not only were aided by our civil society, but later gave back to it through creation of nonprofits, leadership in community organizations and active philanthropy. Immigrants who were grateful to have received help have continued to sustain this spirit of American civil society. For example, Bush describes the story of Javaid Anwar, who came from Pakistan with very little to his name, and after building a successful career has become an icon of philanthropy across Texas. Javaid’s gratitude for America shines through this quote:

That’s what America did for me. It changed my life. It gave me chances I can never repay. The only way I can try is by helping other people out in this country.

Likewise, Kim Mitchell, who came to the U.S. as an orphan from Vietnam, served as a naval surface warfare officer for 17 years, then co-founded the Dixon Center for Military and Veterans Services and managed the Veterans Village of San Diego. She continues to be a leader in veterans services.

Mariam Memarsadeghi, who immigrated after the 1979 Iranian revolution, has dedicated her career to the pursuit of democracy in Iran. She founded Tavaana: E-Learning Institute for Iranian Civil Society, which is reaching millions of Iranians despite Iran’s restrictions on internet access.

Portrait of Annika Sörenstam by President Bush. Image Credit: George W. Bush Presidential Center

There are countless other examples in the book: Bob Fu, a religious dissident from China, founded ChinaAid, an organization that helps Chinese refugees. Jeanne Celestine Lakin, a Rwandan genocide survivor, started the nonprofit One Million Orphans to provide care for orphans around the world. Annika Sörenstam, an immigrant and golf pro from Sweden, launched the Annika Foundation to provide golf opportunities for girls in America and around the world.

In this way, immigrants are carrying the torch of American civil society, which has remained alight from its founding until today.

The Land of Opportunity

The second concept that resonated across the book is how immigrants truly believe that America is the land of opportunity and act on that belief. One particular example stood out to me: Ezinne Uzo-Okoro immigrated from Nigeria and was hired four years later by NASA as a 20-year-old computer scientist. She summed up her awe of the American system this way:

I was impressed by how much value I was given as a person and the value placed on meritocracy. No bribes were required. My parents did not need to know the president of the school. It was incredible!

This pursuit of opportunity is manifested in different ways—through the private sector, social entrepreneurship or public service. I was surprised by how many immigrants in the book were drawn to contribute through public service, including Arnold Schwarzenegger (Austria), former governor of California; Florent Groberg (France), serviceman and recipient of the Medal of Honor; Dina Powell McCormick (Egypt), former assistant secretary of state; Henry Kissinger (Germany), former secretary of state and national security adviser; Yuval Levin (Israel), special assistant to the president for domestic policy; and many others.

Madeleine Albright, who was secretary of state under President Bill Clinton, captured the sentiment well when she said, “Can you believe that a refugee is Secretary of State? That, to me, is the epitome of the American Dream.”

Immigrants as Entrepreneurs

Lastly, for many immigrants, the land of opportunity means they can contribute as entrepreneurs, creating value through products, services and jobs for their fellow Americans. This entrepreneurial spirit runs through many immigrant stories in the book. For example, Salim Asrawi, a Lebanese immigrant who fled from civil war, came to the U.S. in 1981 and founded the Texas de Brazil restaurant, which now has 67 locations across the nation. The founder of Chobani, the top-selling yogurt brand, is a Kurdish immigrant from Turkey named Hamdi Ulukaya.

The book’s depiction of immigrants as entrepreneurs is supported across various academic studies. A study by economists Sari Pekkala Kerr and William Kerr discusses how first- and second-generation immigrants created approximately 40% of the Fortune 500 companies. They further found that first-generation immigrants created 25% of all new firms in the U.S. from 2008 to 2012, even though they account for only 14% of the labor force. Another study found that immigrants show an 80% higher rate of entrepreneurship than native-born individuals and that they start companies quite quickly after entering the United States.

While showcasing the positive impact of immigrants—their entrepreneurial endeavors, public service and leadership roles, and embrace of American values, patriotism and civil society—George W. Bush makes a case for “smart” immigration policy. He argues for increasing overall levels of immigration, creating a better and more efficient system for employment-based immigration, and upholding America’s tradition of welcoming refugees and asylum seekers, while at the same time providing effective border security.

Many current debates have divorced the individual from the abstract concept of “immigration.” But portraits can change policy because they reflect the true immigration story. They cut through rhetoric, can be more influential than political posturing, and strengthen the research on immigration by grounding the data with real stories. We, the immigrants, are people—we have talents, we have innovative ideas, we work hard, we hold good values and we are committed to making America thrive. We continue to be in awe of America’s promise and are deeply devoted to its cause. Reforming immigration policy should be a priority in order to further enhance our country’s vitality and to nurture the American spirit.