Holding Out for a (Byronic) Hero

Pushkin’s ‘Eugene Onegin’ highlights sexual politics and the contrast between urban sophistication and rural simplicity

By James Broughel

We’ve all heard the story of the 30-something guy who spends all his free time playing video games. “Saturday Night Live” cracks jokes about 34-year-old boyfriends incapable of crossing the street or running errands by themselves. Sex is on the decline among millennials, in part due to smartphones and pornographic viewing habits among young men. Women are now more likely than guys to enroll in college and, among those 25 and older, more likely to complete college too.

In short, men are feeling pretty superfluous in today’s society.

Given this context, it was with interest that I recently picked up a copy of Alexander Pushkin’s “Eugene Onegin.” Pushkin is the Russian language’s parallel to William Shakespeare: a romantic poet and literary genius who became a national icon. “Onegin” is probably his best-known work, a novel-length poem published for the first time in complete form in 1833, considered by many to be a literary masterpiece.

Bad boy. Image Credit: Thomas Phillips (English, 1770-1845), "Portrait of Lord Byron"/Wikimedia Commons

Book-length narrative poems like “Onegin” are something of a lost art now. But since the beginning of writing—starting at least with Homer and continuing well into the 19th century—they have been one of the main compositional forms in literature. England’s Lord Byron, a source of inspiration to Pushkin, had published his own book-length poem, “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage,” a couple of decades earlier, and—like “Onegin” would later—it had proved spectacularly popular.

Byron’s “Childe Harold” was an autobiographical poem about a dark and brooding traveler in search of his place in the world. Such a character has come to be known as a Byronic hero in classic literature—something approximating a “bad boy” in modern terminology. Pushkin’s character Eugene Onegin is a branch from the same tree, though perhaps less scarred by his past than is Childe Harold, more bored and less melancholy.

Town and Country

“Eugene Onegin” is the story of a pessimistic yet charming and attractive man from St. Petersburg and his missed opportunity, which he comes to regret, to have a love affair with a young country woman named Tatyana. Onegin is cultured, wealthy, well-read and well-educated. Meanwhile, Tatyana is trusting, innocent and less experienced in the ways of the world. Tatyana is swept off her feet by Onegin’s apparent sophistication and falls deeply in love with him. She writes him a brutally honest love letter, only to be rebuffed: He responds uninterestedly and chastises her for her naivete.

A key theme in the book is the distinction between the cultured urban class and the less sophisticated country folk, whose lives are simpler yet in many ways more fulfilling and richer. This theme resonates strongly today in an American society that is so bitterly divided between rural “Trump country” and urban progressive enclaves.

Having myself lived in New York City for more than a decade in my late teens and 20s, I can certainly recall traveling to parts of America where the latest trends in fashion, art and music had not yet arrived (and often would never arrive) and feeling an air of superiority. There is much to admire about New York and urban culture generally. But, as Pushkin so elegantly points out, the superiority of the urban elite is part of an illusion. Although there are benefits to greater awareness of art and culture, with that awareness often come the pitfalls of pretentiousness and arrogance.

In the second half of Pushkin’s tale, Onegin experiences a reversal of fortune. He crosses paths with Tatyana again years later, after she has grown into a sophisticated woman who is now the wife of a respected military officer. Realizing he misjudged the young Tatyana, Onegin feels a change of heart. However, she is now the one who rebuffs his advances. She admits she still has a love for him, but also that she has moved on and that the time for a love affair is over. Onegin grows misanthropic, depressed and unable to act or feel inspiration.

Superfluous Men

The most interesting part of the poem is a scene in which the young Tatyana, after being rejected by Onegin, visits his home while he is traveling abroad after having killed his former friend Vladimir in a duel. Seeking to better understand Onegin, Tatyana peruses his personal books and notes and realizes that she doesn’t actually know the man. He seems to have adopted attributes of the various characters he has read about, emerging as a kind of amalgamation of his literary heroes.

The real Onegin, if he exists at all, is buried under these character traits that he has picked up through his extensive literary education. This highlights another important theme of the book, which is the double-edged sword of education. While knowledge is surely necessary for enlightenment, the attainment of knowledge leads down a perilous path along which one can easily lose oneself in overconfidence. The economist Friedrich Hayek called this the “pretense of knowledge.” Onegin, if not an empty man, is certainly a lost and cold-hearted one, out of touch with his emotions and unable to empathize with genuinely good people like Tatyana.

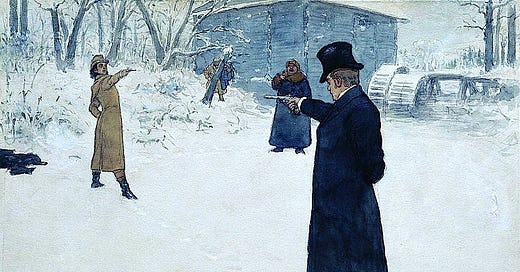

Romantics? Image Credit: Ilya Repin (Russian, 1844-1930), "Eugene Onegin and Vladimir Lensky's Duel"/Wikimedia Commons

The men Pushkin criticized in his day were false romantics. They had read Byron and the other great poets, but they had never experienced real love for themselves and therefore didn’t understand how to give it. While I certainly knew men like Onegin while living in New York, a bigger problem facing men today is probably the changing 21st-century economy and workplace, which is making an old style of man obsolete.

Technology and globalization have made physical strength less of an asset than it used to be. Creativity and the ability to work well on teams, meanwhile, are among employers’ most highly-sought-after skills. Men have no particular advantages in these areas, and so some have responded with bitterness or by checking out.

Interestingly, these modern challenges facing men seem to break down along rural and urban divides, as they did in Pushkin’s time. The educated, intellectual class in cities is perhaps better equipped to handle the gales of creative destruction. But having the intellectual tools to cope with a changing world does not guarantee that one will be emotionally equipped as well.

A true romantic takes his knowledge and applies it in the real world. He shows his partner love, not by emulating the emotions that he has read about in books or seen in movies, but by feeling those emotions from deep within. It is only by bringing together the best from the country and the city life, from education and lived experience, that men can live up to their romantic promise.

Childe Harold and Eugene Onegin could never hope to achieve this—but it’s what good women like Tatyana are yearning for deep down, and it’s what a real romantic hero looks like.