The Future of Historic Preservation: History Matters … But Which History?

The complicated and visceral issue of how we preserve our history offers an opportunity for meaningful discourse

“The ‘historian’ adores the past,” British philosopher Michael Oakeshott once wrote, “but the world today has perhaps less place for those who love the past than ever before.” I have to wonder what Oakeshott, who wrote these words in 1958, would think about the world today? Is there even less room today for those who appreciate the past than there was 65 years ago?

It’s easy to think that at least in America, the answer is yes. We seem to have less respect for, and certainly less knowledge of, our own history than ever before. But for my own part, the answer isn’t completely clear, and that’s because there are some interesting paradoxes here.

We live in a time in which we are largely preoccupied with ourselves and our current lives—one look at social media makes that case. Yet both government and Americans themselves seem to have a greater interest in the way we preserve our history than we have in quite some time—from the way students are taught history to the items and sites from our past we choose to keep. This interest can partially be explained by the increasingly outsized influence of political battles on our society, but also partially by a renewed love for the past and for old things that tell us about where we came from.

Because of both politics and passion, the debate over what our history is has become particularly heated in the last decade. And so it’s a perfect time to reflect on why we preserve our history, which aspects we should and shouldn’t preserve, and how we should go about preserving it. The answers are far from clear-cut, but this lack of clarity creates an opportunity for robust discussion about the fundamental question of what American history is—and ought to be—about.

The Past Isn’t Really Past

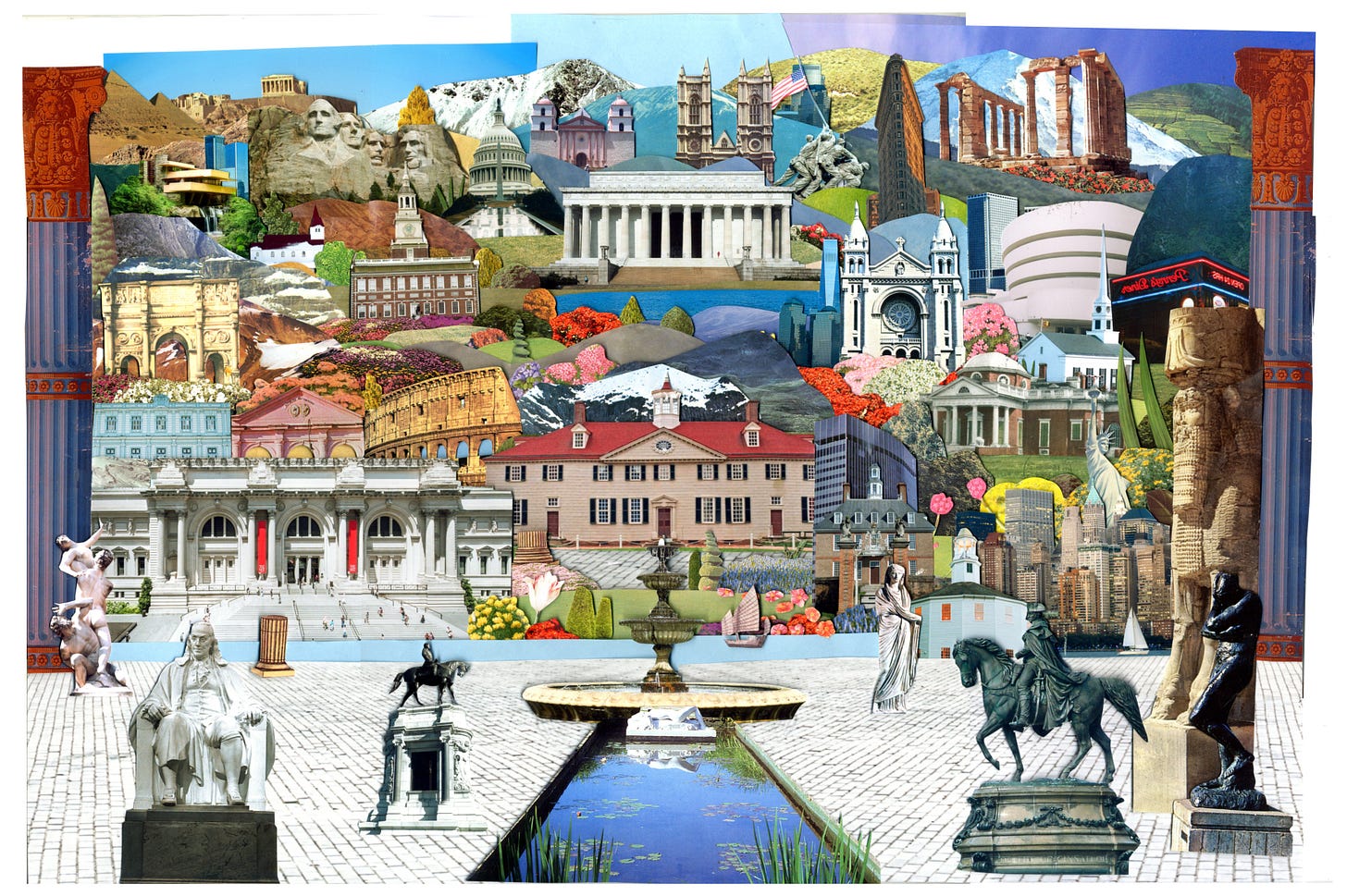

While the term “historic preservation” typically refers to preserving buildings, monuments and sites from the past, it’s really much bigger than that. After all, what is “historic preservation” but the very preservation of our history itself—our stories, actions, customs and perspectives? It can stretch far beyond an appreciation of history into an appreciation of the aesthetic. We preserve certain buildings, monuments, art and even literature not just because they’re old or connected with important people or events, but because they are beautiful. And this can hold true for everything from paintings and sculptures to neon signs.

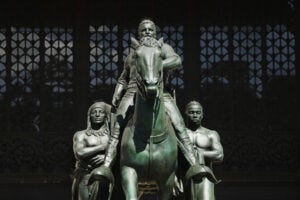

There is a wide range of ways by which we hold onto these aspects of history and pass them along to future generations—and many of these can cause controversy. Take, for example, the question of what to do about public statues of historically significant figures now deemed by many ignominious. The last couple of years have seen the removal of statues of Confederate leaders as well as monuments to Confederate war dead. Statues to other Americans not associated with the Confederate cause, such as the famous monument to Theodore Roosevelt in front of the American Museum of Natural History in New York, also have been taken down for various reasons. These actions have led some critics to claim that statue removal is akin to erasing history—and to argue that it is important that we don’t forget this history, even the ugly parts. On the other hand, supporters of such monument removal say statues play a miniscule role in how we remember our history and often can represent causes, like the Confederacy, that are very offensive to many Americans.

And then there’s the headline-grabbing topic of education, specifically what should children be learning about American history in our schools? Consider the public debates over some schools' use of the New York Times’ 1619 Project—which contends that slavery was the defining event in the nation’s history—in classroom curricula. What may seem to be an essential way of teaching history to one person may seem like “woke” revisionist history to another.

This argument has reached a fever pitch in Florida, where Gov. Ron DeSantis has taken several steps to keep critical race theory out of the state’s classrooms. The issue is just as salient at living history museums like Montpelier, James Madison’s Virginia home, which has struggled with its own internal debates over the interpretation of slavery as part of the visitor experience.

These controversies, while they may be particularly heated today, are really nothing new. New York City’s Landmarks Preservation Commission was founded in 1965 in the wake of the loss of several historic buildings—first and foremost, the controversial demolition of Penn Station to make way for Madison Square Garden. Today, there are currently a whopping 37,800-plus “landmark properties” throughout the city’s five boroughs—and the debate continues to rage over whether this level of preservation is helping to protect New York’s history and culture or hindering economic development.

The point is that while history is the study of our past, our past is really present. It’s present in schools, museums, buildings and historic districts. And it’s present in every debate over what should be remembered and what should be laid to rest.

More Questions Than Answers

History is the warp and weft of our national fabric, but we must choose as a people which materials should make up the cloth—which materials should, taken together, comprise the history we remember and perpetuate as a society. The question of how we go about preserving this history can be a complicated, nuanced and fraught one—and it’s a question that leads to many more questions. Here are just a few:

How do we preserve our past while also protecting individuals’ property rights?

How can we effectively capture our shared experience without crowding out the stories of individuals and groups with different experiences, particularly those ignored or denigrated in the past?

Does preservation necessarily get in the way of economic progress? Or is it possible to save our history without inflicting too much financial damage? And can preservation even yield monetary benefits?

How do we decide what’s “significant” enough to protect? Given how subjective this can be, who should decide what’s important to preserve?

What should the government’s role be in shaping the preservation of our history?

These are not just big and important questions; they’re also quite personal, visceral and subjective. For instance, your views on which buildings, sites and statues are worth preserving likely won’t line up with your neighbor’s, and that person’s views will differ from his neighbor’s, and so on. And even if we all agreed, we’d likely disagree about how to go about preserving statues and sites. Some might say that making these decisions is the government’s job, while others would prefer that the private sector, namely philanthropists and nonprofits, buy a building and preserve it. After all, why should everyone have to pay to preserve something that only some value?

Furthermore, such decisions only capture these subjective beliefs at a moment in time. The needle on history tends to move exceedingly quickly. To give just one example, it took just 30 years for the Stonewall Bar in New York City to turn from the site of a violent police raid against gay and lesbian patrons into a site listed on the National Register of Historic Places. One wonders how many decisions currently being made about what aspects of history to preserve—or not to preserve—will be met with criticism, say, 50 or 100 or 200 years down the line.

The ’Quirky Politics’ of Historic Preservation

Most people would agree that preserving our history offers civic, communal benefits. We all benefit from saving an example of historic architecture, for example, because of its beauty and its role in helping us remember our own roots as a town, a state, even a country. While decisions about which parts of history to preserve can be influenced by politics, the issue of historic preservation doesn’t break cleanly along established political lines.

Indeed, the preservation of our history does bring out, as Duval County, Florida, historic preservationist Wayne Wood said in a TEDx talk on the subject, some “quirky politics.” History is intertwined with so many aspects of our lives—from the very public to the very personal. It’s not a Democratic issue or a Republican one. Not only are there a wide range of views about what to preserve, there are also a wide range of views about how to go about preserving it—and what resources, government and otherwise, ought to be marshaled in the service of that preservation.

It’s complicated for those on both the left and the right. While progressives might not object to the government’s role in determining preservation guidelines, for example, they might recoil at the fact that historic preservation can tighten the supply of available housing and make it less accessible for low-income Americans. Many on the left also are concerned with preservation efforts that directly or indirectly promote people or causes they see as tainted.

But preservation presents a conundrum for conservatives too. Traditionally, conservatism has been associated with the idea of “conserving”—standing in favor of the status quo and against change for the sake of change—and the preservation of American history and culture fits under that umbrella. But the threat that preservation can pose to property rights gives many Americans pause—particularly those with a conservative or libertarian bent.

In a way, this is reminiscent of the debate about what to teach in America’s classrooms: Some conservatives may not agree with what students are taught regarding race, for example, but they may not want the government to take action to, say, ban the teaching of critical race theory outright. Some conservatives may personally believe that a building ought to be preserved, but they’d rather not get the government involved and would instead leave that decision to the property owner, even if that ultimately might result in the building being razed.

Quirkiness + Questions = Opportunity for Discussion

But in the messiness of our differences, there is opportunity. Because the issue of the preservation of history doesn’t fall along clearly delineated political lines, it is more difficult for people to retreat to entrenched political camps without actually considering the nuances of the topic. We’re all familiar with the ways in which political polarization drives a wedge between people and inhibits constructive discussion. Historic preservation isn’t immune to debates based on political divides—see the example of James Madison’s Montpelier—but for many aspects of saving our history, there is not the same deep-seated polarization that infects so many other issues.

Sometimes, in fact, preservation can unite a community. A good example is the fate of the well-known “Tillie” mural in Asbury Park, New Jersey. Asbury Park was a flourishing seaside town in the first half of the 20th century, but by the 1970s and 1980s, many of its buildings had fallen into disrepair. One of those buildings, the Palace Amusements indoor amusement park, was home to the Tillie mural.

When the Palace Amusements building was targeted for demolition because of its dilapidated state, there was an overwhelming outpouring of support for preserving the mural—indeed, public comments in favor of saving the Palace and the mural “outnumbered opponents by a factor of 900-to-1.” While the condition of the building meant it could not be salvaged, developers agreed to remove the Tillie mural from the Palace before demolition and put it into storage. While a new home for Tillie remains up in the air, there’s little doubt that it would have been gone for good without the Asbury Park community’s decisive support for saving the mural.

Maybe because preservation can be less political, there may be more areas of common ground and more opportunities for imaginative solutions and creative compromises. In Denver, for example, Tom Messina, the owner of Tom’s Diner had planned to sell his restaurant—a quintessential example of mid-century futuristic “Googie” architecture—to a housing developer in 2019. But after an outcry from members of the community who wanted to see the diner preserved, he ultimately decided to change plans and reopen it as “Tom’s Starlight” late last summer. While Messina initially disagreed with preservation supporters, he eventually changed his mind and decided to reimagine the space as a cocktail lounge “because I saw the potential.”

The Tom’s Diner story shows that perhaps reinvention is often a good way to keep history alive, while also respecting economic realities. But it also shows that open-mindedness may be a key to the preservation of our history. And not just to keep historic buildings alive, but to keep the sharing and telling of our history alive as well.

Like it or not, history is not based on an absolute set of facts on which we all agree, and it never has been. It’s comprised of different narratives and varying accounts. And the preservation of history depends upon countless decisions—choices about what to remember, choices about the stories we tell and pass along and, of course, choices about what we choose to save and preserve. As with so many issues today, it’s imperative that we talk with one another in an open-minded fashion to determine what that history ought to comprise. It’s alright if we don’t always agree as long as our disagreements are respectful and constructive.

History is not just a fascinating intellectual pursuit, something, as Oakeshott said, to adore. History is our story, the stuff of our national and cultural DNA. It also isn’t just about the past, or even the present. As Winston Churchill famously said, “A nation that forgets its past has no future.” Which is why how we preserve our past—how and what we choose not to forget—is so important.