Having Fun With History

In “Ragtime,” E.L. Doctorow skillfully weaves together a number of themes and characters to capture a period in American history that is not unlike our own

By James Broughel

We all know Harry Houdini, the famous escape artist. But did you know that Houdini was pals with the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian empire, whose assassination in Sarajevo in June 1914 sparked World War I?

Actually, the two probably never met. But that doesn’t matter. Because in the world of E. L. Doctorow’s novel “Ragtime” they did. And it was amazing. Similarly, Henry Ford and James Pierpont Morgan conspired in secret to solve the mysteries of reincarnation. Booker T. Washington was a part-time hostage negotiator, and Sigmund Freud and his young acolyte Carl Jung enjoyed a romantic voyage together through New York’s tunnel of love.

The upside down world characterized in this precious gem of a book stems from it falling in the somewhat unusual category of “historical fiction”: stories that include real life people as characters, but that take great liberties with historical accuracy, for the sake of telling a good story or making a broader point about history.

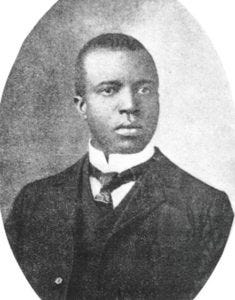

“Ragtime” takes place in early 1900s America, during a time when ragtime music like that of piano composer Scott Joplin was popular. By bringing together themes of immigration, cultural change, strained race relations and debates about the optimal economic system for the nation, the book charmingly captures the essence of a tumultuous period in U.S. history—and, as the above list of issues shows, a time in many ways not unlike our own.

Piano man. The great Scott Joplin in 1903. Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

“Ragtime” is the story of two sets of families, meant to represent essentially anyone’s family. Throughout, the narrator doesn’t refer to the characters directly by their names. Instead, a wealthy family from New Rochelle, New York, is made up of Mother, Father, Little Boy and Mother’s Younger Brother. Meanwhile, a struggling immigrant family living in New York City’s Lower East Side consists of Tateh, Mameh and Little Girl.

Given the very different lifestyles these families lead, one issue the book wrestles with is inequality and what that concept really means. Yes, we all know there is inequality in people’s incomes. Father, an established business owner and born and raised American, and the recent Jewish immigrant, Tateh, have vastly different levels of financial wealth. But, ironically, Tateh often comes across as better off. The entrepreneurial spirit is more alive in him. He’s a striver and ultimately happier for it, especially compared to Father, who is stuck in the past. Thus, the book illustrates how paper wealth can often be an illusion, as those with talent and a keen eye for critical developments are in some sense richer than those who have more dollars in their bank accounts.

Other forms of inequality the book deals with are related to gender and race, and these issues are not nearly so straightforward. Although the character Tateh is mostly likeable, he splits with his wife Mameh after she is taken advantage of by her boss, which resonates as profoundly unfair. Another character, Evelyn, a wealthy Manhattan socialite, is apparently in love with the man who raped her as a teenager.

I like that Doctorow presents readers with a set of facts and then leaves them to stew over this information on their own. “Ragtime” was published in 1975, which perhaps explains why its lessons about gender are subtle.

Coalhouse Walker is another central character in the book. He is a talented, well-spoken and well-dressed black musician. When he is ill-treated by a group of firemen who are jealous of his Model T Ford, he is unwilling to back down from their provocations, and the altercation ends up escalating to an extreme degree.

Anarchist. Emma Goldman in 1911. Image Credit: Library of Congress

Coalhouse’s commitment to justice is laudable, but one has to wonder whether that is the same as acting wisely. In the end, Coalhouse loses everything due to his encounter with the firefighters. A similar series of troublesome circumstances surrounds the political activist Emma Goldman (another real-life person). She likes to agitate crowds at rallies in lower Manhattan. This helps spread her message of anarchic socialism, but all the attention she draws from the government ends up getting her deported. Was it really worth it?

The book thus raises an interesting question. When does sticking to one’s principles become unreasonable, and even counterproductive? Some characters’ behavior quite sensibly leads to a backlash. Thus, it’s not even clear that in the end Coalhouse and Emma meaningfully advance their causes.

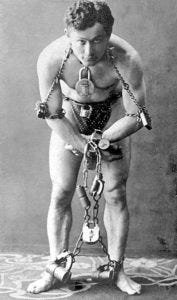

Although Harry Houdini is a somewhat minor character in this book—his actions do not substantially affect the main narrative—he does embody many important themes. He is an outsider, an immigrant on a quest to remake himself. He is also an illusionist, both in terms of his profession and also his social status.

Illusionist. Harry Houdini at work in 1899. Image Credit: Library of Congress

At the end of the day, what Houdini seeks is the approval of the upper class—albeit on his own terms. It’s unfortunately an approval he can never obtain. Social structures ensure that the social hierarchy is maintained, even for those outsiders like Houdini who by chance happen to end up rich. Maybe Houdini’s children will fare better in established society. Still it’s not hard to see why Emma and Coalhouse thought the only path to real reform was knocking down existing hierarchies and building new ones in their place.

“Ragtime” is one of the best books I have read in some time. Fundamentally, it’s about the interconnectedness of life, the hard work that needs to be done to adapt in a world of rapid change, and the subtle injustices that perpetuate in spite of continual progress. Its reliance on real-world people who have a place in the lexicon of American life makes the book in some sense more personal than a typical novel because we begin the story already feeling we know the characters.

This particular book uses this technique to turn our attention to the American Dream and the extent to which it is realized, by whom and for whom. These are questions we should continue to ask ourselves each and every day.